The fix was in from the beginning.

At least that’s the conclusion that could be easily drawn from the way that the Tennessee Valley Authority’s use of 1.3 billion gallons of our drinking water every year as cooling water in the Allen Combined Cycle Plant has relentlessly moved through the approval process.

It has marched forward despite serious questions about its impact on the aquifer that is the source of our water and about the alternative of using wastewater. The amount of drinking water needed by TVA amounts to 10 gallons of water for every household in Shelby County.

It is a curious feature of many public agencies, especially large ones like TVA, that the loyalty by the bureaucrats seems to attach to the agency rather than to the public who owns it. As a result, the public’s concerns get swept aside and calls for greater transparency are treated as unnecessary inconveniences.

Trust Us

We’ve all seen this behavior, such as when it comes to roads and infrastructure. We’ve seen the consequences in roads that are wider than they should be and that fueled sprawl and subsidized developers.

These were gambles that has cost taxpayers dearly, but they pale in comparison to the gamble of being wrong about TVA’s five wells into Memphis Sands, our source of drinking water. The cost of a mistake cannot be overstated except to say it would be devastating to our community.

Built into the process is the attitude that we should not challenge TVA’s technical positions or ask for more information from independent sources. Rather, it’s an attitude anchored in our traditional lack of self-worth. We should simply be grateful for TVA’s investment in our community although it’s not making the investment, the public is.

As happens so often in these kinds of processes, key information is not released promptly or not until the public demands it and even when it is released, it’s often with a “trust us” approach to questioning.

Automaton Board Members

In the process to evaluate TVA’s wells, the bureaucrats predictably pull out the rules and regulations and allow them to trump reason and due diligence. Listening to attorneys representing the Groundwater Control Board and the Health Department, it’s makes us wonder why public boards are needed at all. Automatons can rigidly read the rules and say yes or not. The purpose of the members is to ensure the public good and to act in the community’s best interest.

Sometimes, it’s hard to decide what is more insulting: the refusal by some public boards and officials to consider fully public concerns or that we don’t see all of this for what it is.

The recent Groundwater Control Board’s unanimous vote to reject an argument about the threats to our most precious natural resource – our aquifers – is a case in point. It was bureaucratic theater, because it was clear from the beginning that the seven members had already decided how they were going to vote before the meeting began.

It’s a reminder again of how powerful government agencies like TVA can call in its political chips and turn loose its lawyers to overwhelm the voices of concerned citizens. It causes people who otherwise talk about how important it is to protect our aquifers and water supply to go quiet and line up in support of TVA. Some supporters tout the $975 million pricetag for the new plant, and once again, it’s as if the size of the project means that no one should question it.

As for TVA, it’s headquartered 400 miles away in Knoxville so unlike us, it won’t have to live with any negative impact if the aquifer is contaminated.

Reducing Risks

Scott Banbury, Tennessee Conservation Programs Coordinator at Tennessee Chapter of Sierra Club and Conservation Chair at Sierra Club-Chickasaw Group, and his colleagues deserve our gratitude for their leadership and their questions and requests for information on our behalf, notably testifying to the Groundwater Control Board about current studies indicating leakage from groundwater is already present in the Memphis Sands aquifer and that drilling could exacerbate it. The Sierra Club also suggested that the Mississippi Aquifer could provide an adequate alternative source and that TVA did not give adequate consideration of using gray water for cooling.

Unsurprisingly, TVA assured the Groundwater Control Board that there was no reason for worry, and the board gave the agency latitude in expressing its opinion and did not call for independent collaboration of its positions. As far as we know, there was no testimony about TVA-related pollution that have been problems in other parts of Tennessee, and instead, TVA’s assurances were taken at face value.

Meanwhile, TVA justified its decision to drive five wells into the aquifer on the basis of delivering electricity at the lowest possible costs. There was no discussion about false economies such as whether an alternative would be worth the cost of eliminating any risk to the drinking water, not to mention that the annual TVA budget of $10.4 billion.

This is not to say that we are not grateful for the connection between Tennessee Valley Authority and Memphis, and so is the entire city. After all, downtown’s November 6th Street (formerly Maiden Lane) commemorates the 1934 vote when Memphians approved a relationships with TVA, becoming the first major city to join the new agency.

Flowing Fountain

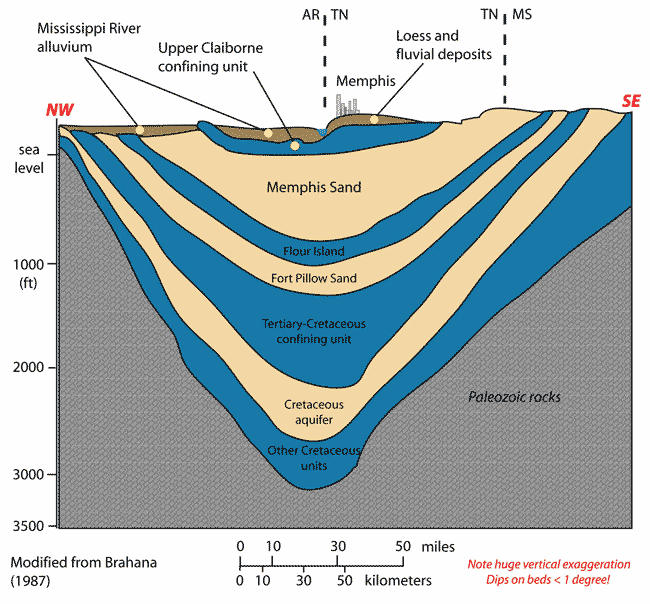

Our Memphis Sands aquifer is nearly 350 feet beneath downtown Memphis and approximately 850 feet thick, and today, we are taking about 210 million gallons a day from it. The Memphis Sands are shallow under the city of Memphis but rise virtually to the surface in the eastern part of Shelby County and Fayette County. The age of the water in the aquifer dates from as little as 16 years ago to as much as 2,000 years, typically becoming older as we go deeper.

Until the aquifer was discovered in 1887 when an ice company drilled a deep well downtown and clear water rushed out, Memphians were getting water from the muddy and polluted Wolf River, contributing to the yellow fever epidemics that racked Memphis in the 1870s. A local official remembered years later that crowds gathered around the “flowing fountain.”

That said, there are few questions that we absolutely have to get right than the one about TVA’s wells in the aquifer.

The Saudi Arabia Of Water

Dr. Jerry L. Anderson, Director of the Ground Water Institute at the University of Memphis, in WaterWorld, saying: “If water is a natural resource that is to be treasured and used like any other natural resource for economic development and other purposes, then it’s clear that the Memphis region is the ‘Saudi Arabia of water’ among the highly populated portions of North America.”

He said Memphis has the “sweetest, most wonderful tasting water in the world,” he said, in part because of the presence of so few minerals that the water can be used with little treatment when it is withdrawn from underground.

In addition, Dr. Brian Waldron, a researcher at the Ground Water Institute, said: “We don’t really know the rate at which the Memphis aquifer is replenished…nor do we know what the potential is for water degradation. Our job is to make certain that we know the answers to those questions before it is too late and to make certain that our water is as plentiful and as of high quality in the future as it is today.”

It’s a seminal point. We do need to know the answers to those questions before it is too late.

Unfortunately, we don’t think the process, including the hearing by Groundwater Control Board, got the answers for us, and because of it, there remains widespread uneasiness about the TVA plans to use 3,500,000 gallons a day for its new plant.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.

Thanks, Tom. It ain’t over yet 😉

Thank you, Tom! This business decision by TVA, which would cost pennies per year for their customers (1/3 of whom affected by this deal do not live in Memphis), reminds me of the disastrous decision of Union Planters to call in their Stax Records loans and auction off the assets cheaply–not realizing how short-term the vision of the assets was. These two seemingly relatively small potatoes, short-run thinking decisions by business entities both end up having disastrous long-term consequences to Memphis and its citizens.

Memphis craves a leader (like, say, a Mayor) who will stand up and fight for its water and environmental justice rights–not one who shows up to the hearing and shrugs, “Oh, well, it was out of our hands.”

Thanks all around, Scott, Webb, Tom, and Folks. But it all seems such a backwards way of conducting the public’s business. Here we are debating whether we should take a chance on polluting our most precious resource—when the bigger discussions should be about innovation and best use of all the other resources involved. Is this a good use for river water? What do we do now with gray water from the Treatment Plant? And when did we have a full and faithful and public discussion of why we are putting all our energy eggs in one basket? A billion dollar natural gas plant with no dabbling in alternate energy sources? What if fracking turns out to be the reason Oklahoma becomes a sink hole? And here in our energy-burdened town, we have little help from a TVA who used to aid and abet weatherization. I guess just selling energy, using local resources to aid and abet profit, is the agency’s mission.

We need a Resource Board with teeth, gumption, knowledge, and a public mission to manage what we hold in common for generations to come.

What about the dangers of such drilling leading to an Earthquake here? We have seen what is happening in Oklahoma and the Dakotas from drilling and we all know that Memphis is overdue for “the big one”.

There is no increased danger of an earthquake in this area due to drilling wells to remove water in the Memphis sands. The earthquakes in OK are due to injecting wastewater into fault-ridden areas much deeper underground than the Memphis Sands. Your comparison is completely idiotic and ignorant. Go study a little geology before making a fool of yourself.

Yes, I agree – the fix was in with regards to TVA gaining access to the Memphis Sands. We were distracted by water quality and it was revenue that drove this deal.

MLGW now has a wonderful new customer and it is infinitely a more valuable company. Additionally, TVA is infinitely more valuable for access to our natural resource.

We Tennessean’s like to privatize government services. We are recognized nationally for its efficiencies and the cost benefits to tax payers. The essential services that MLGW provides and now, access to our natural resources via TVA are services of which must not be sold. We can’t let this leverage get into the hands of a shareholder based entity.

Our dependency on these resources and AFFORDABLE quality of life that they provide is too important to go down the road of privatization.

Please note that the Ground Water Institute (GWI) is now the Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research (CAESER). The director for CAESER is Dr. Brian Waldron. Our web site is http://strengthencommunities.com/. Although our name has changed, we still conduct water research, on groundwater and surface water, locally and globally.