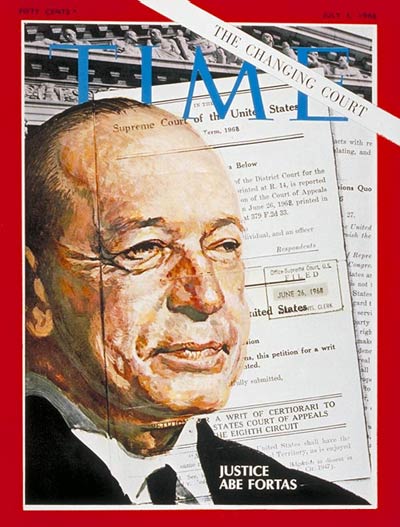

Abe Fortas, the only Memphis U.S. Supreme Court justice and author of landmark rulings, did the right thing when he resigned in 1969 in the midst of a scandal involving his questionable acceptance of money.

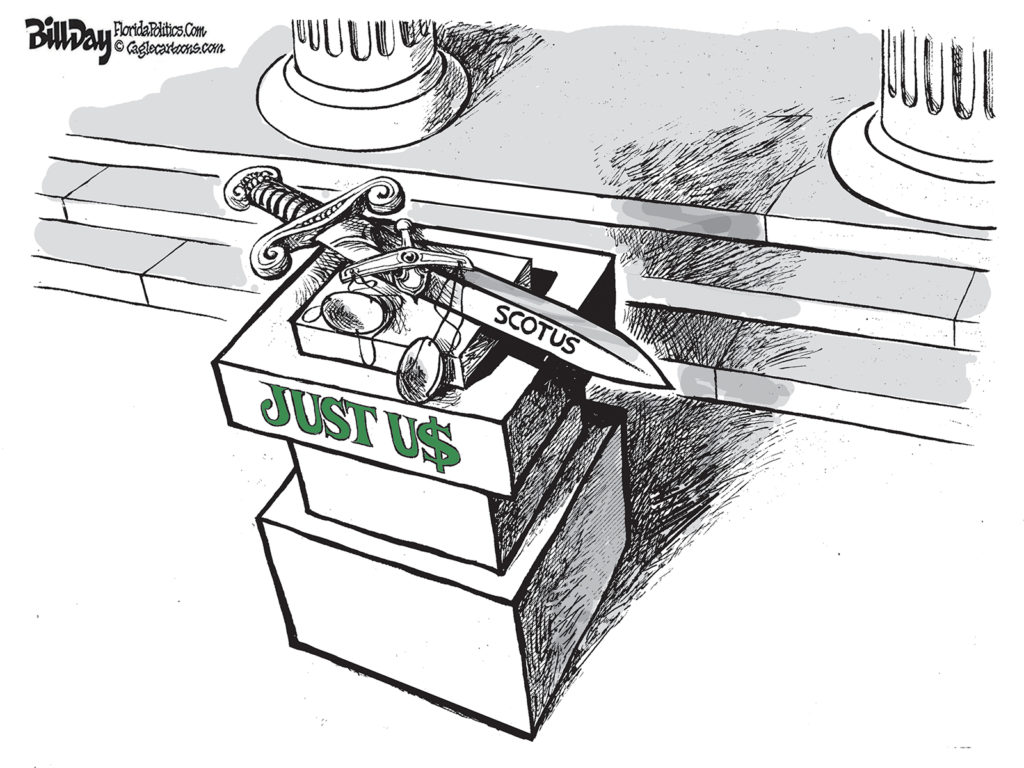

It stands in stark contrast to the stonewalling by current justice Clarence Thomas who has accepted from a Texas developer luxury trips, gifts, purchase of his mother’s house, school tuition for his nephew, and significant contributions to his wife’s causes. The total amount of the gifts are unknown but they could easily amount to half a million dollars.

Justice Fortas was relentlessly hounded off the court by Republican Congressmen. These days, Republican Congressional members have lined up to relentlessly defend Justice Thomas.

The story of Mr. Fortas was resurrected a few years ago in the midst of U.S. Senate hearings for one of President Trump’s controversial nominees and it happened again in the wake of the revelations about Mr. Thomas.

The story of Mr. Fortas was resurrected a few years ago in the midst of U.S. Senate hearings for one of President Trump’s controversial nominees and it happened again in the wake of the revelations about Mr. Thomas.

It’s an instructive chapter in American history for a variety of reasons, but to concentrate on Justice Fortas’s resignation is a disservice to his legacy as one of the most brilliant lawyers who ever appeared before the Supreme Court and later as an accomplished jurist.

His colorful biography – which took him from playing the violin on Beale Street to becoming one of the most influential and powerful men in Washington, D.C., during the administration of President Lyndon Johnson – deserves to be more widely known in his hometown.

Here’s a post about Justice Fortas from April 13, 2017:

Abe Fortas – the forgotten Memphian – has been back in the news lately.

Or more precisely, he has been in the background of the news lately.

First, there was his relevance in the controversy about U.S. District Judge Neil Gorsuch’s nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court, and second, his shadow hung over the Tennessee Supreme Court task force report affirming the right to counsel for every Tennessean.

As a result, it seems a perfect time to remember the missing Memphian, a private man whose life played out in the most public of venues, a man as complex and distinctive as the city where he was born and reared and where his lifelong commitment to fairness and justice was shaped.

Like so many people from Memphis who found fame, he was an outsider, a Jewish boy from a struggling family living a stone’s throw from Beale Street who dreamed of a better life and who witnessed injustice and inequality as he performed his music as a teenager on the legendary music street.

Filibustered

And yet, from this stark, ambition-crushing background, he rose to become a product of New Deal thinking, a powerful confidant to U.S. President Lyndon Baines Johnson, and a U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice. In the decades when he was at the height of his influence, it is hard to think of another American in the legal profession who had greater power over the country’s policies and laws.

Because of his close ties to LBJ, his liberalism, his support for civil rights, and his Judaism, he would ultimately be hounded from the U.S. Supreme Court. It began when the Republican Party and the Dixiecrats of the Democratic Party filibustered the president’s nomination of Mr. Fortas as Supreme Court chief justice in order to block the brilliant jurist from having even more influence in broadening the rights of Americans and ensuring that a person’s outcome in court did not depend on his wealth.

President Johnson understood that Justice Fortas, as chief justice, would continue the  legal legacy of the Warren Court, a thought that was anathema to his conservative opponents, whose successful filibuster of his nomination opened the way to the confirmation of the more conservative Warren Burger. After all, it was an election year, and opponents of President Johnson thought the next president, who was to be Richard Nixon, should make the pick.

legal legacy of the Warren Court, a thought that was anathema to his conservative opponents, whose successful filibuster of his nomination opened the way to the confirmation of the more conservative Warren Burger. After all, it was an election year, and opponents of President Johnson thought the next president, who was to be Richard Nixon, should make the pick.

After President Johnson pulled back his nomination after a vote to end the filibuster failed decisively, it was not long afterwards that Justice Fortas resigned in the face of controversies about accepting outside payments while serving on the court. In truth, the Republicans and anti-civil rights Dixiecrats had never put their knives away after the filibuster, and Mr. Fortas had no hope of surviving the controversies which were notable for their intensity and blizzard of code words. In a way, it all presaged the scorched earth politics that dominate today.

Senate’s Dishonorable Chapter

Unfortunately, Justice Fortas did not return to Memphis, because if anything, Memphis is a city of second chances, but long before, Mr. Fortas’s live had unfolded in his new hometown of Washington, D.C., where he was earning as a private lawyer the equivalent of $1.4 million today.

Today, the treatment of Justice Fortas’ nomination as chief justice is seen by historians as one of the most dishonorable actions of the U.S. Senate, and it’s hard to imagine that President Barack Obama’s Supreme Court nomination of U.S. District Court Judge Merrick Garland – who was kept from even a committee hearing for almost a year – will be seen any differently in the clear-eyed lens of history.

Speaking of the lessons of history, with the blocking of Mr. Fortas, conservatives enjoyed immediate gratification, but they were made to pay for their actions. That potential remains today in the wake of the confirmation of Judge Gorsuch after Mr. McConnell upended the Senate traditions he avers to respect to get him approved.

As for Mr. Fortas, he rose from a Southwestern at Memphis (now Rhodes College) graduate (and later with a law degree from Yale University) to become legal and political adviser to Lyndon Johnson as he climbed from U.S. Senator to Senate majority leader to vice-president to president. Along the way, Mr. Fortas helped write Great Society legislation, major presidential speeches, and legislation establishing the Kennedy Center following the assassination of its namesake. His unchecked access to Mr. Johnson speaks volumes about his value and influence.

Devoted to Civil Liberties

Mr. Fortas played this role while building one of the Capitol’s most prominent and important law firms. He represented people smeared in Senator Joseph McCarthy’s “red scares” and won, winning praise for his courage and devotion to civil liberties in staring down the master of the Big Lie. While most lawyers avoided anything or anyone labeled as Communistic, Mr. Fortas stepped forward, and his law partner described it as “an act of outstanding courage. Nobody was willing to stand up then.”

A law partner pointed out that half of the firm’s work was defending federal employees accused of being disloyal or Communist sympathizers and asked, “Why do we have to do it?” Mr. Fortas answer was simple and characteristic: “Because no one else will.”

That same devotion to civil liberties was seen in his willingness to represent cases pro bono that expanded individual rights and due process rights that made him a lightning rod when his name was advanced as the nominee for chief justice.

The filibuster exposed the underbelly of Senate bigotry. Justice Fortas was called a “leftist” by West Virginia Senator Robert Byrd who had filibustered the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (he once had recruited 150 friends to create a new chapter of the Ku Klux Klan), he was denounced by Louisiana Senator Russell Long as one of the “dirty five” working to expand the rights of the accused; racist Mississippi Senator James Eastland condemned him, and Arkansas Senator John McClellan, who opposed President Dwight Eisenhower’s decision to send federal troops to integrate Central High School in Little Rock, referred to him as “an SOB.”

South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, who unconvincingly claimed he was not a racist while opposing desegregation and every civil rights measure of the day, claimed that a “lame duck” president should not pick the Supreme Court Chief Justice although there was no precedent for contending that a president could not nominate a justice until his successor was elected. This perverted position about presidential power was applied last year to the nomination of Judge Garland to block his vote as a Supreme Court justice.

Changing the Course of History

If the quality of a person is reflected in who his friends are, it is just as reflected in who his enemies are, and in this regard, Justice Fortas’ enemies said volumes about his unflagging commitment to fair play in the justice system.

The attacks on him were relentless, vicious, and personal, and while he could be combative and was experienced by bare knuckle politics, his opponents used past and pending court cases to smear him with proxy issues that painted him as sympathetic to the counter culture raging at the time, resistant to laws to get tough on criminals and weaken anti-obscenity laws, and too concerned about race and poverty.

In effect, the filibuster was really about putting the Warren Court on trial.

That said, today, Justice Fortas’s rulings are backbones of our criminal justice system and his defenses of the First Amendment are widely accepted as mainstream thought.

However, if the conservatives in the U.S. Senate set out to destroy a voice that was persuasive in articulating the importance of applying the full meaning of the U.S. Constitution to every American, they were successful.

In denying Justice Fortas, they also changed the course of history, because easy to imagine the ways that Justice Fortas could have continued his righteous fight for fairer criminal justice and broader children’s rights. That said, his legal work led to a revolution in juvenile justice, a priority no doubt shaped by experiences on Beale Street when he was well-known as “Fiddlin’ Abe.”

Children and Youth Become People

Unquestionably, his impact on juvenile justice can be seen in the ruling he wrote In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1. In that ruling, youths were for the first time guaranteed the same due process rights as adults, including the right to be notified of a charge in a timely way, the right to confront witnesses, the right against self-incrimination, and the right to counsel.

Remarkably, these rights were denied to youths until Justice Fortas’ opinion in 1967. Until then, state governments were seen as having parental rights in children and youth, so they largely did as they pleased when it came to young people charged with delinquency.

”Under our Constitution,” Justice Fortas wrote, ”the condition of being a boy does not justify a kangaroo court.” And yet, that is precisely what most children faced when brought into court. Even today, the justice’s opinion remains the yardstick for judging whether juvenile courts are meeting their mandate for justice.

The landmark ruling came in the Gila County, Arizona, case of 15-year-old Gerald Francis Gault, who was taken into custody allegedly for making an obscene phone call. A juvenile court judge sentenced him to the State Industrial School until he reached the age of 21. In other words, he was sentence to six years, but if had been an adult, he would have been sentenced to six months.

The ruling meant that children became people in the eyes of the law, and Justice Fortas’ opinion is recognized as the most important children’s right ruling in history.

Guaranteeing the Right to Counsel

That the landmark ruling was the product of a Supreme Court Justice from Memphis is little known known in his home town. It is a remarkable fact, considering that when measured by his impact on our nation, he should be mentioned in the same breaths as the legendary musicians and entrepreneurs whose names we have all committed to memory,

And yet, the ruling transforming the rights of children and youth was not his only reason for fame, as we were reminded earlier this week when a special committee of the Tennessee Supreme Court issued a report that concluded that justice in Tennessee is still too often the result of the size of a defendant’s wallet.

The task force chaired by former Tennessee Supreme Court Justice William C. Koch Jr., issued strong recommendations to guarantee that defendants in criminal court and children in juvenile court are provided competent and independent legal representation.

For far too long, the playing field has not been level with poorly paid and overworked defense attorneys confronting the weight, might, and resources of state prosecutors.

The report referred to a Supreme Court ruling from 1963 when the justices ruled in Gideon v. Wainwright that every defendant – regardless of their economic and social status – has the right to an attorney. In the case, Clarence Earl Gideon was accused in 1961 of committing a burglary and the judge refused to appoint a lawyer for him although he was too poor to hire one himself. He was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison.

The U.S. Supreme Court reversed the conviction in a unanimous ruling and remanded the case to Florida. With the ruling, the unshakeable right to counsel was firmly entrenched in American justice as a result of a passionate, brilliantly constructed appeal by an attorney appointed by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Justice Douglas William O. Douglas said it was “probably the best single legal argument” in his 36 years on the court and it was argued by a superlative legal craftsman. The argument was direct and easy to understand: an accused person cannot effectively defend himself.

The attorney: Abe Fortas.

A Hero To Celebrate

The Gideon ruling led to the creation and expansion of public defender offices across the U.S., and it is an interesting footnote that Mr. Fortas had been reared in a city with one of the first public defender’s offices in the U.S. – created in 1917.

To read more about this landmark case, read Lurene Kelley’s outstanding article in the Memphis Law Magazine, Summer, 2014.

The legal career of Mr. Fortas is marked by even more milestone cases and rulings that defined American justice as we know it today and propelled the promise of justice laid out in the nation’s founding documents. Unfortunately, the brilliance of his legal career is overshadowed by his exit from the Supreme Court in the wake of scandals about accepting money from outside interests while serving as a justice.

All of us want to be judged by the totality of our lives, and not by our episodes of human frailty. No one deserves this measure of fairness more than a man whose life was devoted to fairness itself, especially for those so often denied it because of their age, their poverty, or their race.

As we approach the 200th anniversary of Memphis’ founding and we raise up the heroes of our history, if Justice Fortas is not at the top of that list, we should be shamed for allowing an unbalanced chronicle of his remarkable life to obscure his accomplishments.

Like Memphis’ best music and entrepreneurial breakthroughs, his legal legacy remains just as alive today as it was when it was formed and it is worth celebrating.

****

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis and the conversations that begin here.