England’s Sir Peter Hall, internationally known urban scholar, planner, and author of more than 30 books, died Wednesday at the age of 82.

We mention it because he was author of a favorite book, the 1,168 page tome, Cities in Civilization. While it is an instructive book for anyone interested in the story of Western civilization told through the histories of its greatest cities, it is required reading for anyone living in Memphis.

In his 1998 book, he describes the golden age of 21 great Western cities over 2,500 years. Beginning with Athens and Rome, moving on to Florence, London, Paris, Vienna, and Berlin, explaining the significance of Manchester, Glasgow, Detroit, San Francisco/Palo Alto/Berkeley at the dawn of the age of innovation, visiting New York and Los Angeles, and exploring the marriage of art and technology in Memphis: Soul of the Delta from 1948-1956.

Memphis is paired with Los Angeles in the chapter on “The Marriage of Art and Technology.” Professor Hall writes that in Memphis, “a remarkable event in human history took place: cultural creativity and technological innovation were massively fused…The special reputation of the place, free and wide open, helped it all to happen…the music of an underclass could literally become the music of the world…This was a revolution in attitudes and behavior, as profound as anything that has happened in the last 200 years.”

Mass Culture

In explaining the significance of Memphis in the “invention of mass culture,” he wrote:

“Memphis was the place where two great folk-cultural traditions came together: the Afro-American blues of the Mississippi Delta region to the south and the white country music of the Appalachian hill country to the east. Each of these traditions flourished in other places; the blues in Kansas City and, above all, in Chicago; country music in Nashville and a score of smaller places. But in no place was it so statistically likely that the two streams would meld to produce something different. Further, Memphis from its earliest days had the reputation of a wild city, a place where almost anything could be allowed to happen. It was perhaps the one place in the old American South, even before the civil liberties movement transformed the region, where black and white cultures could cross-fertilize in this way…

“Memphis is as strange a story as Los Angeles, for all the previous stories of cultural innovation have told of old cities dominated by elites of royal blood or aristocratic lineage or at least bourgeois wealth, which patronized and nurtured forms of high art. But Memphis, like Los Angeles, was different in every way: a new city, albeit a city segregated by race and by class, the regional capital of a miserably impoverished and subjugated rural underclass, whose music was borrowed and fostered by local entrepreneurs and local performers, finally transforming it into the global popular music of the mid-twentieth century.

“More specifically, there was not one underclass but two, one black, one white, living lives that were almost equally basic, rigidly segregated, hostile almost to the point of paranoia. They created different kinds of music, each reflecting a long folk tradition: one out of Africa, developed through experience of slavery and sharecroppping; the other out of northern England, southern Scotland and northern Ireland, evolving through centuries of life on remove Appalachian hill farms. They heard each others’ music from afar, subconsciously absorbing bits of the other tradition; and finally, in the summer of 1954, through the mediation of radio and the recording studio, the two traditions explosively fused in Memphis and in the person of Elvis Presley.

“The Memphis story is thus the quintessence of a recurring theme in this history: the outsiders, coming into the city and creating something strangely new and different. It is a long tale, but richly worth the telling.”

Mythic Memphis

What follows in his book is a 56-page chapter that dissects the events, the technology, and the talent that burst forth in Memphis in the form of new music. The following are some excerpts that are relevant to us because they mention characteristics that still reside in the city character, many of them simmering below the surface and waiting for the opportunity to again explode into something new:

“Memphis was the Delta’s capital and its outlet to the world; and, like any port city, it had two faces, sharply distinguished by racial segregation: a strait-laced white side and ‘a night side, which was a rip-roaring town to match anything the frontier West could dish up, with whorehouses and gambling, saloons on every street corner, rotgut liquor, marijuana, codeine, and cocaine for the asking’ (Bane, White Boy Singin’ the Blues). Its core was Beale Street, which had more whorehouses per square mile than anywhere in America outside of New Orleans. By the early 20th century, Memphis was already Murder, USA, the most dangerous place in the country: by 1916, it had 89.9 murders per 100,000 people, the highest rate in the United States.”

“As someone put it, ‘Fate and history had somehow conspired to push Memphis a few degrees out of phase with the rest of the South.’ Jack Clement, once a producer at Sun Records, thought everyone there was crazy. Judd Phillips, brother of Same Phillips of Sun and former manager of Jerry Lee Lewis, said that ‘the poor blacks and the poor whites were coming together as early as 1900, playing music’; the white sharecroppers, he said, who were working next door to the blacks, would come and hear them on Saturday nights…Conway Twitty, the country singer, grew up playing a combination of blues and country. ‘It was like there was a magnifying over Memphis,’ he said. ‘It was bigger than life.'”

The Great Convergence

“The music was the blues, which some observers have called the true, the fundamental American music. But in origin the blues are African music, and they are one of the very few African cultural elements that survived in America. Anthropologists have found all manner of African elements in the blues…”

“The other strain that came into Memphis came from the hill country to the east, and it was a white strain. Like the blues, its origins lay a long way back in the history of the South. the migrants originated especially in countries bordering the Irish Sea: Ayr, Dumfries, and Wigtown in Scotland, Cumberland and Westmoreland in England, and Derry, Antrim, and Down in Ireland, all of which constituted a single cultural area. In the 19th century, they became famous for their xenophobia and the violence of its expression. They detested the great planters and the abolitionists in equal measure, and in the Civil War, some fought against both. From this culture came country and western music.”

With the advent of radio, Memphis became the African-American broadcasting center of Memphis and heralded the era of the disc jockey. The established music industry fought back by banning songs from the radio, harassing new rock singers from Chuck Berry to Jerry Lee Lewis, but in the end, the dam had been broken – rhythm and blues and country music had melded and become rock and roll – and there was no turning back.

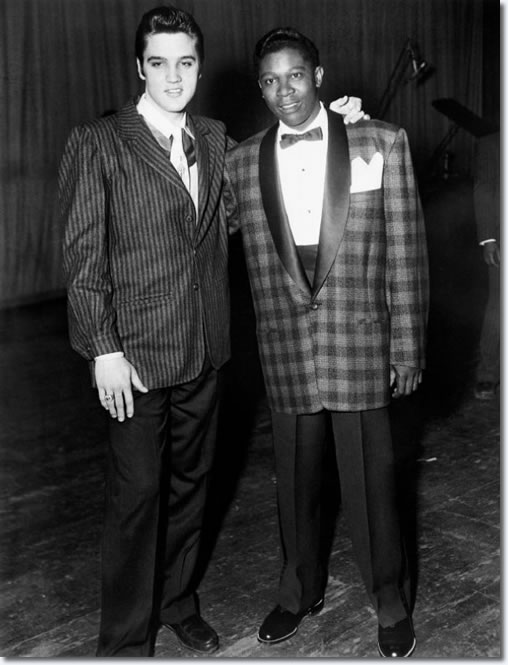

Elvis Presley and B. B. King, 1956

“So rock ‘n’ roll would have been born somewhere in America, some time in those years of the mid-1950s. It might have happened in a number of places: Chicago, for instance, perhaps Detroit. But it was more likely to happen in Memphis than anywhere else, and it did. The reasons lay in the special position of the city at the junction point of different traditions, different migration streams: the rural blacks from the cotton fields of the Delta, the rural whites from the hill farms. They had interfused to a great degree, greater than many appreciated, greater perhaps that they themselves appreciated, even before coming to the city; in the city, the fusion was completed. And the special reputation of the place, free and wide open, helped it all to happen. The new entrepreneurs were more likely to emerge here than anywhere else, because to succeed, they had to understand the music, and more of them were more likely to show more understanding than in any other city.

“What the Memphis story finally shows is that the music of the underclass could literally become the music of the world. That represented the final breaching of the dam, which 19th and early 20th century bourgeois society had erected, to try to exclude a form of expression that it regarded as menacing to mainstream values…it as an important part of the creation of the multi-cultural society of the late 20th century in which America has played such a large part. Echoes of that diffusion can be found in earlier cultures, as when Viennese composers borrowed peasant dances to provide the basis of the waltz, a revolution as shocking in its day as the rock revolution was a century after. But the barrier between the Viennese bourgeoisie and the Austrian peasant was never as great as that between white and black in Mississippi, or even in the north cities; this was truly a revolution in attitudes and in behaviour, as profound as anything that has happened in western society in the last 200 years. And the music, destructive, anarchic, hedonistic, played a central part of it.”