The United States has always had difficulty discussing race, not just the way that a new white democracy was founded on black oppression in the 18th century but the federal policies in the 20th century that limited opportunity and prevented African-Americans from obtaining wealth in ways available to Caucasians.

While the recent Atlantic magazine article on reparations is must reading for anyone who cares about the history of African-Americans in America but also anyone who wants to understand why black Americans are wary of promises by this country to improve things, not only do many politicians act like reparations is a four-letter word, but the advances made by African-Americans are being ripped from them on a regular basis – from cuts to the federal human services programs to programs for cities to the Supreme Court’s death blow to the Voting Rights Act, ushering in another version of Jim Crow-style voter suppression legislation.

As a result, white Americans welcome opportunities to “tsk-tsk” comments by billionaire racists and redneck ranchers while turning away from any serious discussion about the governmental actions that prevented home ownership – average American’s greatest source of wealth – up into the 1960s, the role that government policies played in the predatory lending that robbed black Americans of what they did have, and the structural obstacles that continue even today.

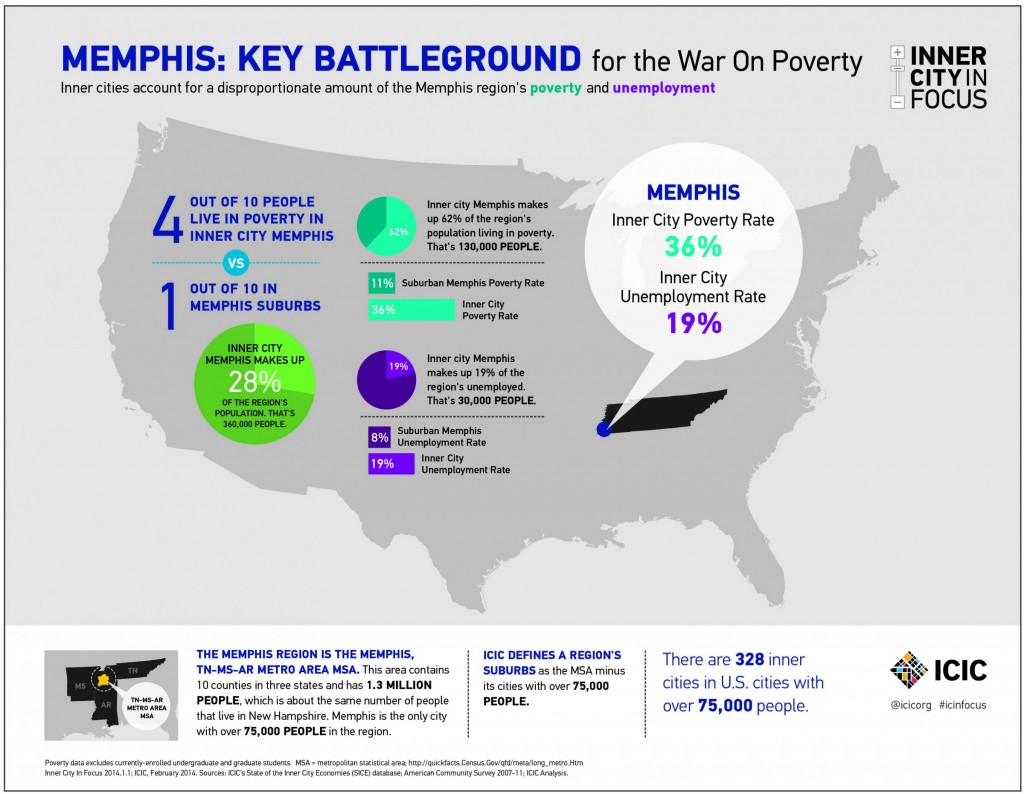

Meanwhile, a majority of Americans still delude themselves into believing that everyone has the power to pull themselves up by their bootstraps and pay significantly more attention to what Kim and Kanye are doing than the concentrated poverty that is a birthright of children born into too many urban census tracts. The inner city poverty rate in Memphis for children is 40%, and the overall poverty rate is 36% in the inner city; however, in five census tracts, the poverty rate is more than 60%.

Dealing With Facts Rather Than Anecdotes

What is most remarkable is not that America has difficulty having an honest, serious conversation about race but that Memphis, a city that is 63% African-American, isn’t able to show the rest of the nation how to do it. And because we don’t, we make expansive statements like those about the importance of minority business while we fail to dig beyond the anecdotes and talking points to develop an effective program that can set national standards for developing black entrepreneurs, for growing black-owned businesses, and for setting up government policies that are serious about supporting them.

It is often said that Memphians talk too much about race, but the truth is that it is rarely the kind of talk that results in change. For that matter, it’s not the kind that even clears the air and moves us toward a civic agenda in which we prove that we can be a hub of African-American talent and businesses and that we prove that a majority African-American region can prosper.

With only about two and a half years left in his administration, President Obama has given signs that he might be willing to begin such a discussion. We were hopeful that the All My Brother’s Keeper program would be a catalyst for that discussion, but so far, the program seems to be a litany of familiar statistics and a compendium of tried and true recommendations like mentors, community policing, reductions in school expulsions, more high school and college graduates, summer jobs for youth, and reading programs.

It seems that the honest discussion that should have been a prelude to these recommendations has been stepped around, so as happens so often, the report appears to be aimed as much at making everyone comfortable than pressing people to engage in the forthright discussions that are needed to hear what African-Americans see as the roots of the problems and the potential for solutions. Too often, even successful African-Americans feel constrained – and are offered too few opportunities – to provide their most straightforward thoughts in mixed racial company.

Clustered Into Low-Paying Jobs

So far, the City of Memphis Blueprint for Prosperity – Mayor A C Wharton’s plan to reduce poverty from 27 to 17% in 10 years – has been direct in its purpose and its explanations, and organizers of the program have indicated an interest in openly addressing the connection between race and poverty that limits civic cohesion, pride, and economic performance in our region.

Following the lead of President Obama, the city program should emphasize the challenge of African-American boys and men. Today, young black men find themselves virtually locked out of employment opportunity. Their high unemployment rate has been persistent and historically intractable, and as the New York Times pointed out in 2010, the great recession was a devastating blow to African-Americans.

It’s no wonder. Nearly half of African-American men who are employed work in the two occupational clusters with the lowest wages, and this has remained unchanged for the past 20 years. While college enrollment for young black men increased from 16% in 1970 to 33% in 2012, they lag when it comes to college completion (although white high school dropouts are hired at a higher rate than black high school dropouts).

Meanwhile, the prison-industrial complex delivers a debilitating blow to employment prospects. African-American men 18 and 19 years old are imprisoned nine times the rate of Caucasians and African-American men 20-24 years of age are imprisoned at more than seven times the rate of Caucasians. Sixty percent of employers say they will not hire an ex-offender.

Lasting Damage

Memphis is among the 40 cities which have the lowest percentage of employed African-American men – 53.2% (it was 67.9% in 1970). Non-Hispanic white employment was 75.9% (which is higher than Nashville).

To further complicate the problem caused by the fact that only about one in two African-American men are working, the average annual weeks of work dropped from 41 weeks in 1970 to about 38 weeks. In those decades, the percentage of black men with college degrees increased from 2% to 10%, and the percentage of white men climbed from 11% to 26%.

The seriousness of these discrepancies has profound impact in Memphis. A new study released two weeks ago by the Center for Global Policy Solutions and the Network on Race and Ethnic Inequality at Duke University concluded that African-American households’ wealth is only six cents for every dollar of wealth owned by a typical Caucasian household and the average liquid wealth for the black household is only $200.

Prayer for the City, the book chronicling Ed Rendell’s mayoralty of Philadelphia, referred to the “redlining” of African-American neighborhoods which prevented homeownership and resulted in the federal government creating the ghetto “in terms that were blatant, racist, and unsanitized, (the federal government) aided and abetted that destruction while opening up the flood gates of the suburbs.”

“The lasting damage done by the national government was that it put the seal of approval on ethnic and racial discrimination and developed policies which had the results of the practical abandonment of large sections of older, industrial cities,” wrote Kenneth Jackson. The sad chapter of redlining is well-known and the response by the federal government was largely a shrug.

Media Myths

Joe Cortright, in his paper, Neighborhood Change, 1970 to 2010, wrote that the number of high poverty neighborhoods in the core of metro areas has tripled and their population has doubled in the past four decades. Considering that individual opportunity these days is largely determined by the neighborhoods in which we live, it is an ominous trend for Memphis, where economic segregation exacerbates an already serious problem.

According to Richard Florida and his team at Martin Prosperity Institute, the Memphis MSA is #2 on the list of the most income-segregated large metros in the U.S. The same research group determined that the Memphis MSA is #1 among large metros where the wealthy are most geographically segregated. We’ve written often about the implications of economic segregation, so we want repeat it here, but suffice it to say that it creates barriers to opportunity.

These structural issues define the reality that confront the search for real solutions, but there is power in understanding them and that has been the missing piece in policy development for so long. It’s a gap in understanding that exists because it requires a difficult, painful conversation and we would prefer to avoid it. And yet, it’s important if we are to move beyond superficial solutions and have the kind of breakthroughs that position Memphis to be a leader in dealing with race.

As it begins, we need to admit that the post-racial narrative is a myth. Capitalism and the American Dream have failed in moving African-Americans from the shoals of the economy to the mainstream. The post-racial narrative regularly overshadows the facts that show that African-Americans are a long way from inclusion and financial security, and in fact, they still today face discriminatory laws and practices that prevent the accumulation of assets while the news media focus on the celebrity status of a handful of sports and entertainment stars and peddle the myth that race doesn’t matter.

It all begins with a honest, open discussion, and it’s hard to think of a more appropriate place for it than here.

The conversation does not need to be had by anyone else but us, the Black community! What part have we played in keeping ourselves in poverty, last in line for jobs, first in line for the prison system and welfare! The only real way is to quit leaning on the crutch on racism and discrimination and have an enematic discussion amongst ourselves. Let’s lay it all on the line and clean from within. 2 Timothy 2:15 says “Let us present OURSELVES approved as to God, a WORKMAN who need not be ashamed and who CORRECTLY HANDLES the word of truth.” Have we really done that?

We don’t see racism and discrimination as a crutch. It is a real force affecting the lives of black Americans, and it is impossible to deny these realities with a clear-eyed, objective examination of current federal policies and recent trends to roll back advancements. It seems to us that the people who want to argue that poverty isn’t really the problem and that people can pull themselves up if they try hard enough are the ones leaning on the crutches of cliches and platitudes.