The following article was written by a favorite Memphis economist of ours, David Ciscel, former Chair of the Economics Department, Associate Dean of Fogelman School of Business, Dean of the Graduate School, and Senior Consultant for the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, and honorary Memphian Michael Honey, author of Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther King’s Las Campaign and Sharecropper’s Troubadour: John L. Handcox, the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, and the African American Song Tradition. We appreciate them allowing us to post it here.

July-September 2016 Volume 25: Number 3

Memphis 50 Years Since King: The Unfinished Agenda

By David Ciscel & Michael Honey

David H. Ciscel (ciscel@bellsouth. net) is Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Memphis. Michael Honey (Michael.K.Honey@gmail.com) is an American historian, Guggenheim Fellow and Haley Professor of Humanities at the University of Washington Tacoma.

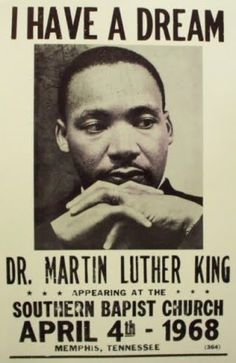

Memphis, infamous as the place where Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968, is a river town based in the Deep South with a long and problematic history. Nearly 60% African-American, the city remains number one in poverty and infant mortality for any U.S. city of its size (Lamar, 2004). In this article we provide a sketch that might help us to understand why, despite Black advances in civil rights and political power, struggles for economic justice remain so central to continuing the civil rights revolution in the Deep South.

Memphis remains largely a poor community. At the center of the Mississippi Delta plantation economy and as transshipment point for goods and services produced elsewhere, it has always suffered from a weak industrial base. And, like the rest of the Deep South, its long history of white supremacy, low wages, and weak and segregated education has damaged the economy and left a litany of problematic issues

* Poverty encompasses one-third of the African-American community.

* Only 35% of African Americans over 25 years of age have a high school diploma, and only 14% of those have college degrees.

* In 2012, whites had a median in- come of $52,102, while African Americans had a median income of only $27,814, a little more than half that of whites. This is only one indication of the racial-economic disparities deeply etched in the economy.

* In 2012, Memphis unemployment rates were 9% for whites and 12.0% for African Americans, but the true statistic for Black unemployment in the center city and among youth are much, much higher.

* In 2012-2013, 82% of City school children remained economically dis- advantaged, and most of those children were African-American (McFerren and Soifer, 2014).

Why do the city’s racial-economic disparities remain so enduring? While much has changed in the Memphis economy since King’s day, the low-wage model remains.

As described in more detail below, the Memphis employment picture is a difficult one for the Black community as a whole. While it is clear that African Americans have entered every occupation in substantial numbers, the regional economy is clearly rigged against affluence for all. First, employment has stagnated since the Great Recession. Second, employment in the region is skewed toward occupations that do not require as much training and education. Finally, the income disparities between the small numbers of high-income jobs (in the $60,000 to $100,000 per year range) and the large mass of jobs (in the $30,000 to $35,000 per year range) skew the economic picture against Black workers.

Some praise the Memphis economy as diversified, but it remains highly dependent on a transshipment economy with an erratic demand for workers. FedEx, one of the largest logistics and package delivery companies in the world, is the city’s largest employer. This places Memphis firmly in the realm of the modern global economy, but one that retains a company town employment structure. This dependence on transshipment keeps Memphis stuck with an old economy in the midst of what looks like a modern logistics and technology revolution. And the burden of its racial history continues to weigh heavily on its economic progress.

Historically, the city has always been economically dependent on the Mississippi River and the other small rivers nearby—the Wolf, the White, the Hatchie, and the Nonconnah Creek. In the antebellum era, white businesspeople like Nathan Bedford Forrest, a founder of the Ku Klux Klan after the Civil War, sold slaves “down the river” to New Orleans. After the war, rivers, rails, and highways intersecting Memphis made it an agricultural trading post and a successful city. It later became a center for intermodal trading of all sorts. Today, the warehousing for goods from China and elsewhere brought by rail from the west coast, the airport, the interstate highways and the river today propel the future of much of the Memphis economy.

The power structure of the city continues banking on the city’s role as a distribution, retail, and health industry center in the global economy to move it forward, even as the city’s history of slavery and segregation continue to weigh heavily on its future. It has another history of worker struggles for racial and economic justice, higher wages, and working-class rights and benefits. From the 1940s through the 1960s, industrialization and unionization brought many workers into the “middle class,” meaning people could buy homes and send children to college. Numerous Black workers who had previously been shut out of well- paying jobs provided a powerful core for unionization in the city. Industry always played a small but important role in the Memphis economy, however, so that organizing service sector and public sector jobs remained the crucial next step for Black workers. All of this led up to the epochal Memphis sanitation strike of 1968, which forged a labor-civil rights alliance encouraging unionization of Black workers across the South (Honey 1999, 2007).

In the wake of that strike, public employee unionism came into its own as the most important force moving workers in Memphis and elsewhere— and especially Black and women workers—forward. The regional economy and employment structure seemed to be improving: new industries employed black workers on the line and some of them gained higher-skilled and supervisory employment. Yet the failure of the RCA television and electronics plant, moved to Memphis to escape higher wages and benefits in the north, exemplified another problem: employers still sought a low-wage economy that kept African Americans from advancing economically. At RCA, Black workers did not settle for low wage jobs, and through union organization, strikes, and agitation tried to secure a more powerful position within the company. Rather than ac cepting the higher-waged, unionized model, RCA picked up and moved overseas (Ciscel, 1976).

Following the example of RCA, in the 1970s and 1980s, Memphis went through the deindustrialization that plagued many Midwestern cities. While Memphis could not claim the title of a “postindustrial city,” it lost many important plants: television production, furniture, tires, food processing, agricultural processing and implements plants all vanished. The loss of the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company and International Harvester eliminated some of the best paying, unionized jobs available to Black as well as white workers. Deindustrialization proved particularly painful for the Black working class. Just as Black workers gained a foothold in the middle class through unionized employment and the civil rights revolution, manufacturing jobs slipped away due to automation and the movement of industries beyond southern borders and overseas (Newmann, 2016; Honey, 1999).

Throughout the 1960s and for a long time afterwards, African Americans with significant support from whites made progress in dismantling the barriers of formal and informal racial segregation, and yet racial-economic disparities remained. The region spent the end of the twentieth century recovering from deindustrialization. White collar and pink color jobs replaced blue collar jobs, with career ladders based on education or certification rather than seniority. Numerous jobs opened in logistics and transportation, providing new sources of Black employment. But these jobs remained mostly non-union, often on- demand (with neither full- nor part-time employments), and lacked comprehensive benefit packages. Local public sector unions organized after Dr. King’s assassination, including sanitation, police, and fire fighters, remained the bulwark of the unionized economy. But unionization among production and most other workers largely disappeared in the Memphis economy.

Some held to the illusion that racial barriers of the past had also disappeared. Black workers seemed to be in every sector of the Memphis economy. African Americans enjoyed access to public accommodations, education, and public offices. Black politicians came to dominate the city, the regional governments and, for a time, the main Congressional seat. African Americans came to lead the police department and made up perhaps as much as half of the police force, undercut- ting a long history of almost unbelievable police violence.

Economic and political conditions in the early twenty-first century seemed poised to substantially improve the Memphis economy. By the end of 2007, 655,000 jobs existed in the Memphis regional economy with only 631,000 workers vying for those jobs; officially, only 5.5% of the workforce was unemployed. Although manufacturing now made up less than 10% of jobs, expanding employment in trade and transportation, education and health care, made up for most of the job losses in older sectors. While wages and benefits may not have matched those once offered in unionized manufacturing sectors, increasingly women and people of color had access to growth segments of the economy.

The Great Recession and the Post-Segregation, Post-factory Economy

Then the Great Recession hit in 2008 and pulled back the curtain in Memphis, just as Dorothy had at the Emerald City. Begun as a bursting real estate bubble, the downward spiral first captured the local finance sector and then began working its way through the other sectors. The number of jobs in Memphis shrank quickly to 590,000 in 2010. Trade and transportation, the core of the regional economy, shed thousands of jobs. Education and health services, largely supported through government expenditures, became stagnant. In 2009, regional unemployment hit double digits, and remained at 9.7% at the end of 2010.

The collapse of home ownership at the root of the recession proved especially disastrous. The percentage of home owners in the Black community fell —largely due to the impact of the Great Recession—from 53.5% to 50.4%, after Black homeownership had reached a peak of 54.2% in 2004. Wells Fargo bank (which settled a Memphis housing discrimination case for its sub-prime mortgage practices for $400 million in 2012) and others had loaned money to people who clearly could not afford to pay their mortgages. Banks and finance companies made millions by securitizing those unviable loans to global financial institutions. In the nearby suburb of Frayser, boarded up homes, shuttered churches and schools, rising crime rates, and a sense of hopelessness replaced a once optimistic working-class environment in which homes had provided a family’s greatest economic asset (Honey, 2016).

The Black community has not recovered from the housing or the jobs crisis. The American Housing Surveys of 1996, 2004 and 2011 show that the number of Black households rose from 153,400 in 1996 to 226,400 in 2011, increasing the overall Black household percentage in the eight-county Memphis MSA from 38.2% to 47.1%. But African Americans had smaller houses (in square feet) than the community as a whole, and dramatically lower household incomes: a mere 62.2% in 2011 of the community average. And while Black homeowners saw the current values of their homes rise from $53,861 in 1996 to $78,826 in 2004 to $80000 in 2011, their relative conditions of home ownership have not improved. Relative to the purchase price, homeowners’ equity had fallen from 133% to 115%, and Black homeowners’ home values remained substantially less than the overall median house value in Memphis. Black household income, for renters and owners, rose from $22,525 in 1996 to $29,554 in 2004, but fell to $24,000 in 2011.

In an era in which home ownership has dropped to its lowest level since 1965, and in which racism still strongly influences who banks will lend to, African Americans in Memphis did not make significant progress in accumulating the primary source of wealth for most families—a house—over the 1996-2011 15-year period (US Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 1996, 2004, 2011).

Economic recovery also proved slow and weak in terms of jobs. By the end of the 2015, 18,000 fewer jobs existed in Memphis than in 2007. Al-though the number of Memphians working or looking for work had fallen to 622,000, now fewer jobs than workers looking for them existed.

Official unemployment had fallen to 6.1%, still higher than before the Great Recession, and significant numbers of uncounted workers had dropped out of the job market. Although employment in education and health services had expanded significantly, trade and transportation had not recovered to pre-recession levels. Manufacturing provided a mere 6.8% of the regional jobs (The Labor Market Report).

The Great Recession had an especially devastating impact on African Americans in the central city and in the region; upward movement to equality for Black people stopped in its tracks. As the job base shrank, Black workers often found themselves unemployed without any hope of future employment, with official unemployment levels stubbornly at twice the official unemployment rates. Full-time employment proved difficult to find, as many employers, particularly in trade and transportation, offered only part-time or on-demand employment. Benefits, already weak before the recession, became a luxury.

The mantra of almost every city mayor in the United States today is jobs, jobs, jobs. For that reason, many cities and states have instituted vast “subsidies” and “tax deferrals” for new employers who transfer offices or plants. Memphis is no exception. Known for its extensive use of tax incentives, the City has still failed to deliver sufficient job growth, while subsidies to business partially cripple its tax base. Hopes for economic development are behind efforts to “improve” educational quality in the region so that workers will be “ready” for new jobs, and behind the various advertising campaigns to get the city perceived as a creative, dynamic, millennial friendly place. But in Memphis, as in most cities, long-term trends and business cycles overwhelm these efforts for short term gain.

The Great Recession brought economic growth to a grinding halt. Since the bottom of the recession in 2009, jobs have come back only very slowly. And unemployment has been reduced not only by new jobs but also by the loss of many workers from labor force participation altogether. The supply of workers is now greater than the supply of jobs, so the bargaining power of workers, always weak, has been further sapped. But more importantly, new jobs are not the real answer to the problems that face a diverse labor force like Memphis. Over the years, Memphis has, relative to its population, had a lot of jobs, but many were really not worth having.

What Kind of Jobs, and for Whom

Beyond jobs, there is the issue of the kinds of jobs that are created. For example, Memphis has seen rapid growth, like many other cities, in medical services. It is a sector that actually escaped the downward pull on jobs during the recession. But medical services tend to be dominated by jobs without internal career ladders (that is, you must leave the job, get training and gain certification before advancement can occur). In transportation and warehousing, part-time and on-demand employment often prevails over normal 40-hour jobs. And almost all new jobs shift the burden of retirement savings to the employee, so that benefits are eroded. While advertising emphasizes the need for highly educated or trained creatives, the actual new jobs are often employments that only require brief on-the-job training sessions. These issues affect all workers, but Black workers especially.

Finally, who gets what jobs is as important as the number of new jobs and the kinds of jobs. While the racial distribution of employment in Memphis has changed dramatically since the 1960s, the earning potential in the Memphis economy has stagnated, like the total growth of jobs, since the end of the recession. For example, EEO-1 data for 2007 and 2014 indicated that total private sector jobs fell over the recession and into its recovery. Almost half (49.3% in 2014) of all private sec- tor jobs were held by Black workers. While Black employment in managerial jobs rose slightly from 21.4% to 23.2%, Black workers remained dramatically underrepresented in supervisory jobs. The same is true for professional and technical type occupations. African Americans are proportionally represented in sales and clerical occupations (49.6% in 2014), but underrepresented in craft jobs (34.8% in 2014). By contrast the number of operative, laborer and service jobs fell between 2007 and 2014, but Black worker dominance of these occupations rose fairly significantly.

As the distribution of jobs in the total economy and for Black workers indicates, there is a dominance of low-paying jobs in the Memphis economy and Black workers tend to be crowded into those occupations. Managerial jobs in Memphis (in 2014) paid, on average, $93,760 per year. Business/Finance jobs paid $62,870 and engineering jobs paid $73,400 per year. Those three job categories make up less than 10% of all jobs in Memphis. Production jobs paid $34,530 per year. And clerical workers in Memphis earn $33,980 per year while materials movers (often in warehouses) earn $32,240 per year. And these three lower-paying occupational groups represent 37% of all jobs in Memphis (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission).

And so the experience of the Great Recession reflects the contradiction of the last 50 years. The American economy seems to have successfully integrated consumption: racial stereotypes no longer dominate the advertising and social media of American society, and public accommodations are available to all. But the ability to maintain the myths of television advertising are laid bare by the underlying income story. And the tale of Memphis is indicative of the plight of minorities and the poor in general. As former Memphis Mayor A C Wharton put it, the economic overlays of class and race now constitute the greatest obstacle to completing the legacy of the civil rights revolution (Honey and Wharton, 2016).

The Great Recession halted forward progress in income growth and wealth accumulation in the Memphis Black community. It also revealed that eco- nomic progress had been far slower than many had thought. Conditions today hark back to Martin Luther King, Jr., speaking in Memphis on March 18, 1968:

“You are reminding, not only Memphis, but you are reminding the nation that it is a crime for people to live in this rich nation and receive starvation wages… Now the problem is not only unemployment. Do you know that most of the people in our country are working every day? (applause) And they are making wages so low that they cannot begin to function in the mainstream of the economic life of our nation.”

Speaking at Mason Temple to an overflowing audience of hundreds of Black men on strike and thousands of people supporting them, Dr. King declared, “You are going beyond purely civil rights to questions of human rights.” King came to Memphis as part of his Poor People’s Campaign, seeking to bring together a mass coalition of the poor, including African Americans, Mexican Americans, Native Americans, and poor whites. Congress and the nation, he said, should guarantee a basic standard of living—decent housing, health care, education, and meaningful employment—for all (King, 1968). King called on the city government to recognize Local 1733 of AFSCME and agree to check off union dues from the workers’ pay checks, something Memphis Mayor Henry Loeb vowed he would never do. The union victory that followed King’s death helped to open up a new chapter in the city’s labor history, but workers and African-American workers have also suffered defeats that under- mine the legacy of the Black freedom struggle. Nationally, Republican Governors like Scott Walker in Wisconsin have drastically rolled back the employee collective bargaining rights that workers won in Memphis in 1968.

King in Memphis linked together equal access to well-paying jobs, decent housing, education, health care, and incomes, declaring, “Now our struggle is for genuine equality, which means economic equality.” King called his campaign for economic justice “phase two” of the freedom struggle. Some 50 years later, Kind would support today’s cries for “$15 and a union) and our larger demands to restructure the American economy on behalf of the 99%. The struggle for labor rights and decent employment, as King insisted in 1968, today remains central to improving the log of the multi-racial working poor and working class and to continuing the civil rights revolution in the Deep South and across the United States.

|

Everyone should read this article. It explains so much.

The image of Memphis was forever tarnished by the assassination of Dr King here in 1968