So what do you get when a city becomes needy, lacks self-esteem, and has no economic development plan to define its priorities?

You get Electrolux’s one-sided deal.

You get corporations and developers who don’t pay $800 million in taxes over 10 years.

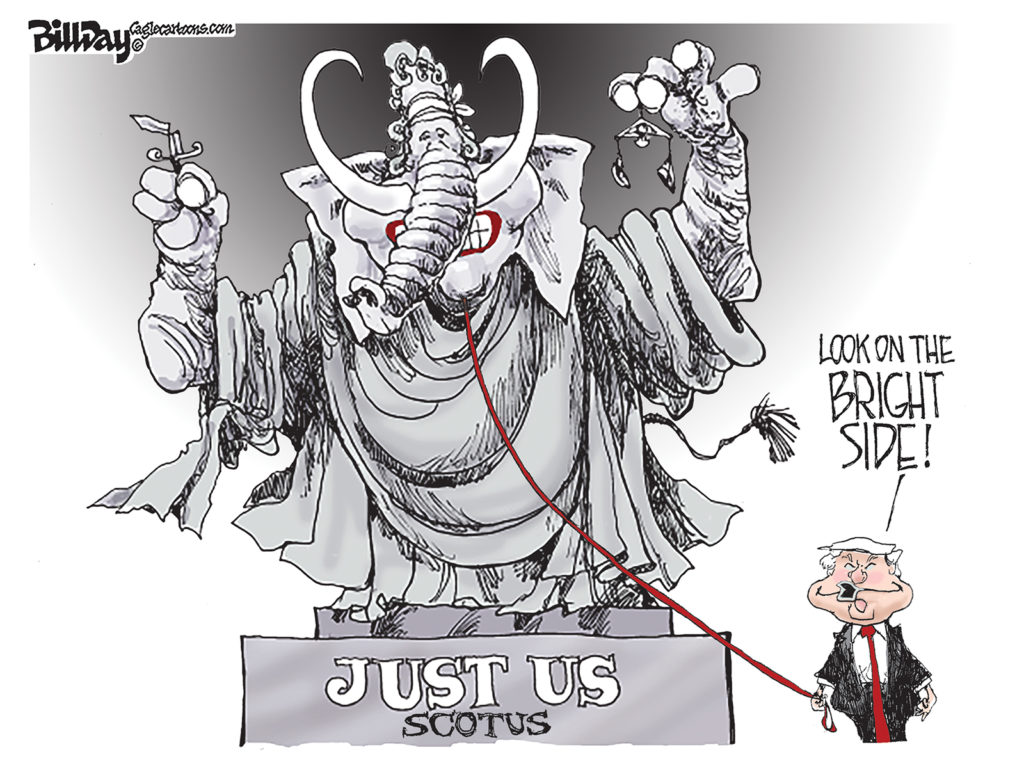

You get the Memphis and Shelby County PILOT program, which, put another way, you see in a “trickle up” redistribution of wealth as a community racked with poverty and income disparities watch as national and multi-national corporations are not asked to pay their full share of taxes at a time when vital public services are underfunded and expanded services are badly needed.

It’s not like we shouldn’t have been suspicious of Electrolux all along. After all, when it moved to Memphis from Quebec, it did not fulfil its Canadian agreement and left after receiving incentives there.

Shuttering Plants: An Electrolux Tradition

That’s not to mention that the Swedish manufacturer has a history of manipulating governments chasing manufacturing jobs. The Memphis plant will be the second plant that it’s closed in Tennessee – the other in Bristol about a decade and a half ago – and its promises to the plant in Springfield have run hot and cold for years.

There are shuttered plants across the U.S. landscape that attest to the way Electrolux chases cheap labor around the world (its Thailand operations were legendary), Electrolux has a well-deserved reputation for union-bashing and busting and its poor human resources practices have rumbled for decades, including at its plant in Middle Tennessee.

In other words, it seems that the city, county, state, and city-county Industrial Development Board all had on rose-colored glasses when they negotiated the Electrolux deal in 2010. With enthusiastic cheerleading from the Greater Memphis Chamber, the deal essentially meant that taxpayers built the factory for an international corporation with revenues of more than $15 billion a year.

All told, the taxpayer incentives totaled $188.3 million (and that’s not even counting the several hundred acres of land thrown it at no cost) and the project included both a PILOT and direct funding from both City of Memphis and Shelby County. The direct funding would take the form of $20 million in bonds from both city and county governments, which means that while the attention now is about getting Electrolux to pay its full tax burden, the real expense to the public are the yearly bond payments that will continue for at least 20 years.

Now, To Pay For Those Bonds

Those bond payments will total about $3.8 million a year so even if today’s politicians are successful in getting blood out of the turnip in the form of an agreement made by yesterday’s politicians, it is likely to only cover a couple of years of bond payments, which leaves 18 more years for taxpayers to foot the bill for the plant.

There is happy talk that the empty 750,000 square foot plant now becomes a competitive advantage for our community in recruiting a new tenant, and we pray they are right. However, we remember something similar being said when the International Harvester plant and the Firestone Tire and Rubber plant announced within one month of each other in 1983 that both were closing. Four and a half months ago, the Greater Memphis Chamber said it was seeking state incentives to reactivate the still closed Firestone factory, once upon a time the largest farm equipment manufacturer in the entire South.

Those plants were built in Memphis decades before our community decided that we had to give away taxes to get major corporations to love us – and now we give them even more to get them to stay once they come. It was a time when our economic development and public officials sold Memphis and Shelby County for the productivity and work ethic of our workers, who today are treated as “less than” although an effective, coherent workforce development program remains to be created decades after the establishment of the programs charged with making that happen.

The real outrage in the Electrolux “deal” is that despite being urged to include clawbacks, penalties, and other provisions to protect the public’s money and its interest, negotiators for government removed them time and time again. As a result, despite the massive public investment in Electrolux, governments gave up an ownership stake in the factory, which is why, if the past is indeed the greatest predictor of the future, we should be prepared for the call by some elected officials for Electrolux to turn over the property to government could prove difficult.

Not Really Negotiating

If anything, the Electrolux agreement is powerful proof that the adage is right: if you’re not prepared to leave the negotiating table, you’re really not negotiating.

Put simply, there was no real negotiation with Electrolux, and we fear that this still happens in in various degrees even today with other negotiations, particularly when it comes to the flaws in the current PILOT program as shown in the so-called retention tax freezes.

We should spare ourselves from the happy talk and the justifications in the wake of the Electrolux calamity and take a clear-eyed, dispassionate look at where we are and why we are susceptible to market forces that place more and more importance on talent and quality of life. Electrolux officials were quick to assure local officials that its decisions was “not about Memphis,” but in truth, it had a choice between Memphis and Nashville and it chose Nashville.

It was reported in Canada that when Electrolux moved to Memphis, it was to eliminate unionized workers in Quebec, so the vote by the workers here to join the union no doubt was a barrier to keeping the company here. That said, it has a history of moving from places with unions to places without them to be able to pay lower wages to its workers. In coming to Memphis, it lowered the amount that it paid its workers by one-third to about $14 an hour. As usual, news releases at the time included the average salary instead of the mean salary so the large salaries at the top skewed the average and made the salaries look better than they were.

Meanwhile, an EDGE official said that “we” had made money off the deal, apparently pointing to the fact that local taxpayers were paid 25% of the total taxes that the company would have owed without a PILOT. That’s hardly dispensation that offsets $188 million in incentives, and by the time it announced its planned exit, it had less than one-half of the number of workers it promised when the massive incentive was granted.

Edward Glaeser, the Harvard economist and author of Triumph of the City, spoke to Leadership Memphis in 2012, and his words ring out today: Government should not be in the business of picking winners and losers, because it’s simply not good at it.

In the wake of the Electrolux collapse, it’s hard to argue with him.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis and the conversations that begin here.

So who were the “negotiators” on our behalf who refused to insist on clawbacks and other penalties? And why did they not listen to common reason and basic principles of contract law? They should be required to pack their bags and leave with Electrolux. Why can’t we learn our lesson – Electrolux is not the first company to walk away and leave us to pay the tab.

Memphis Kong history of weak “leaders” of all stripes are totally responsible for this debacle. Even though we gave away millions with incentives and more, Electrolux clearly wanted to be close to the “it” city of Nashville, not backward and stupid M-town. Will we ever learn?

Memphis long history of weak, gullible “leaders” of all stripes are totally responsible for this debacle. Even though we gave away millions with incentives and more, Electrolux clearly wanted to be close to the “it” city of Nashville, not backward and stupid M-town. Will we ever learn?

Memphis history of weak “leaders” of all stripes are totally responsible for this debacle. Even though we gave away millions with incentives and more, Electrolux clearly wanted to be close to the “it” city of Nashville, not backward and gullible M-town. Will we ever learn?

What a huge waste. Pity the employees. Bad decisions.

Thanks for a great article Tom.

I’m no mathematician but I always thought the average and the mean were the same. Did you mean to say that they reported the “average rather than the median”?

My analysis is generous while referencing public documentation. IF Electrolux gives plant back and we can quickly get a tenant, pain won’t be so severe. I see major challenges beyond Electrolux within Memphis Corporate Community Leadership but Electrolux serves as an open wound of a culture of 1 sided corporate/real estate deals that undermine true economic development. Here is my analysis and feel free to poke holes in it. It’s designed more to give the current conversation a quantitative context than to be right http://mcclmeasured.net/electrolux/

Electrolux was Phil Bredesen’s parting gift to Memphis. Being that Electrolux still has to factory in Tennessee the state should penalize them for closing the Memphis factory, but I know they’re not going to do it. However, I am hopeful the Chamber will be able to attract another company to the Presidents Island location.

I can only imagine what the State and Nashville gave Amazon.

This is one huge slap in the face to Memphis and setback for lical business. The newer plant is here but they are keeping the older one in Springfield? Makes no sense. What company would want the facility? Finding a replacement will take s long time.