The recent ultimatum in Chancery Court from the heirs of Memphis’ founders would have done their ancestors proud.

After all, the city’s mythologized founders were used to giving orders and expecting people to do what they said. There was a Tennessee Supreme Court Judge, John Overton; an Army General and future U.S. President, Andrew Jackson; and an Army brigadier general, James Winchester.

But more pertinent to Memphis than their titles, all three were slave owners and land speculators from Middle Tennessee.

Their maneuvers to claim the wilderness land on the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff of the Mississippi River speak to the influence and power they exercised in federal and state affairs. While the quick pay day they were looking for on the banks of the Mississippi River was mostly elusive, they were willing to play hard ball in the courts and in Nashville to get and protect their land scheme while doing their best to ignore any rights of the people already living there.

The founders set a tone that appears to have been resurrected by three heirs who said about the Promenade in Chancery Court: we are the “legal owners of the Bluff site and the legal owners of the adjacent property to the north and west of the Bluff site.”

It was tantamount to a slap in the face of the Memphians who for generations thought the much-loved public space was in fact space that belonged to the public.

Do Three Heirs Speak For All of Them?

The three heirs of the founders – often referred as the “Overton heirs” – lent their weight to a lawsuit filed by Friends For Our Riverfront to stop construction of the new downtown Memphis Brooks Museum of Art and to receive a declaratory judgement giving them broad authority over what can ever be done on the Promenade.

The lawsuit was filed in Chancery Court against City of Memphis and Memphis Brooks Museum of Art Inc. As a court of equity, Chancery Court operates within the legal system but rather than focus purely on application of the law, it looks at cases and determines outcomes based on what is fair, equitable, and reasonable.

This lawsuit by the three heirs – there are hundreds of others across the U.S. – is complicated by the fact that citizens of Memphis have paid millions of dollars over 150 years for the upkeep, the maintenance, and the improvements of the Promenade.

It is also complicated by the poor form inherent in the White heirs of the White slave-owning founders and mainly White riverfront activists, after decades of the public being told they are the owners of this land, now tell majority African American Memphis it doesn’t belong to them.

No Objections to Other Promenade Projects

Friends For Our Riverfront contends that the easement on the Promenade is sacrosanct although historically that has not been the case.

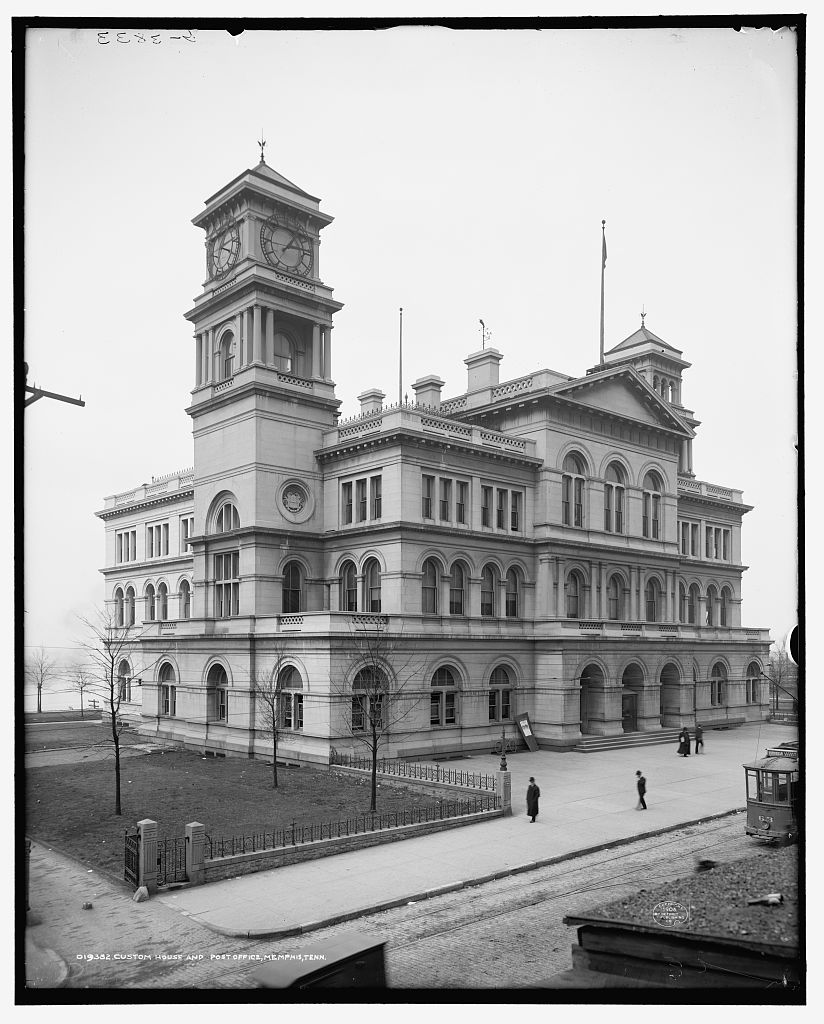

The U.S. Custom House – now the University of Memphis Law School – was built in 1876 when the heirs were only two generations removed from the founders themselves and included wealthy grandchildren active in real estate and banking. For example, at the time, the grandson of the founder, also named John Overton, was especially influential. He was shortly to become head of the Memphis Taxing District (and essentially act as mayor) after the city surrendered its charter after being mauled by yellow fever.

The U.S. Custom House – now the University of Memphis Law School – was built in 1876 when the heirs were only two generations removed from the founders themselves and included wealthy grandchildren active in real estate and banking. For example, at the time, the grandson of the founder, also named John Overton, was especially influential. He was shortly to become head of the Memphis Taxing District (and essentially act as mayor) after the city surrendered its charter after being mauled by yellow fever.

No objections by the heirs can be found to construction of the Custom House.

Then, there was construction of Cossitt Library which opened its doors in 1893. A speaker at its opening hailed it as “the people’s university.” Of course, what he really meant was “White people’s university.”

Then, too, there were no objections in 1952 when a campaign was launched to construct a statue honoring the President of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, in Confederate Park (now Fourth Bluff Park). The mayor of Memphis was Watkins Overton, great-great grandson of the founder John Overton and a lieutenant for E. H. (Boss) Crump’s political machine.

The statue was dedicated in 1964 to “a true American patriot,” three months after passage by Congress of the Civil Rights Act. It was an unmistakable White  supremacist message to local civil rights leaders to stay in their place. The park also had other Confederate markers and at one time, four Civil War replica cannons on the easement.

supremacist message to local civil rights leaders to stay in their place. The park also had other Confederate markers and at one time, four Civil War replica cannons on the easement.

No complaints by the heirs can be found.

Ironically, until demolition for the art museum, the Memphis Fire Department headquarters sat on the exact site that is the subject of the Chancery Court lawsuit and it shared the block with an unsightly public garage operated by a private company. The heaquarter was built on the promenade and easement in 1967, and a plaque in the building said Fire Station #5, built in 1881, was once located on the site.

Heirs Say, We Own The Promenade, Not Citizens of Memphis

The heirs’ past acquiescence seems to defy the contention in their lawsuit that “the City does not have any right to claim legal ownership of the Public Promenade,” adding, “It does not have the right to claim any equitable interest in the land above and beyond what the Citizens have, which is the right to use the land as a promenade.

“The City does not have any lawful authority to use the Bluff Site for an art museum or parking garage…The Public Promenade is not the place for an art museum filled with a private art collection, owned by a private corporation, and managed by a board that makes decisions outside of the public eye.”

It seems a gratuitous dig at the Brooks Museum Board since Friends For Our Riverfront is also a private corporation managed by a board that makes decisions outside of the public eye. And there is no private art collection. City ordinance makes that clear.

Founding of Memphis Was About Profit, Not People

Memphis is a city of myths and its founding has its own share.

Notably, there is the mythic image of the founders of the city proudly standing high on the bluff, looking westward across the river’s expanse inspired by their vision of a great city to be called Memphis.

The scene never happened. The truth is that the three founders were never in Memphis at the same time, and Andrew Jackson likely never visited at all and was mostly an uninterested investor in the real estate development.

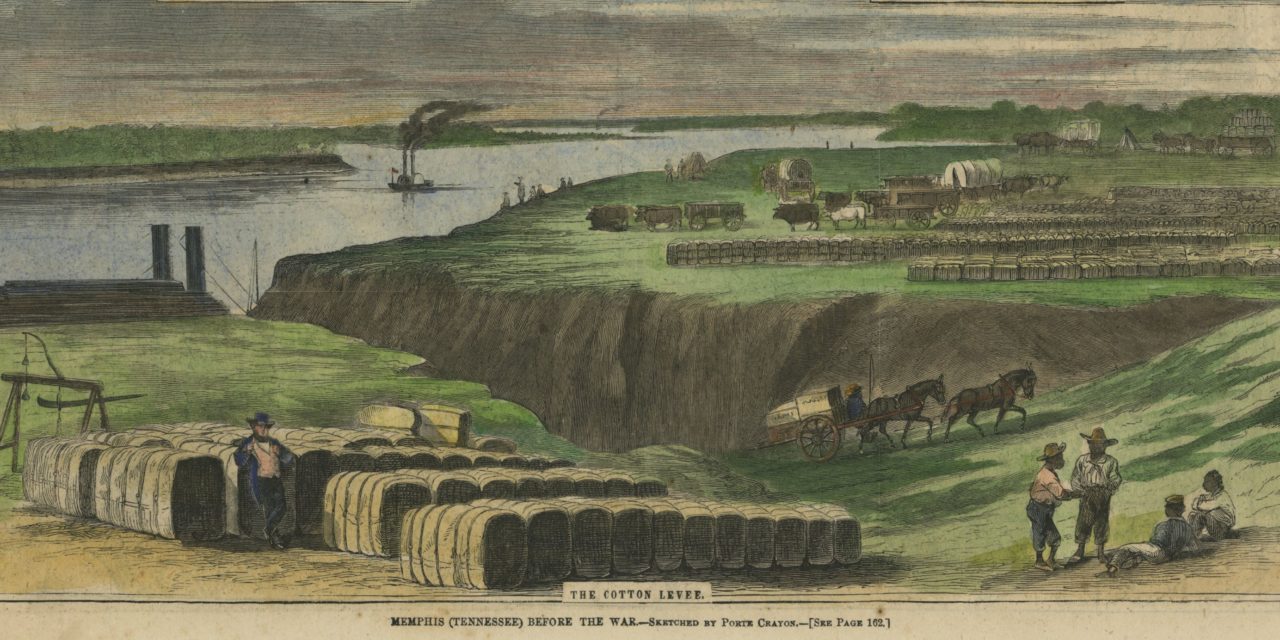

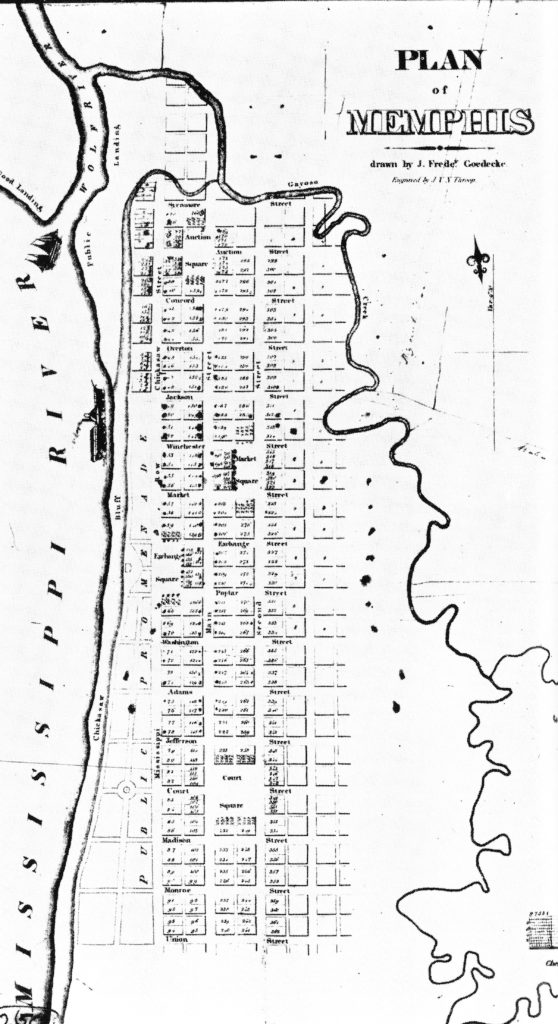

Memphians are forever grateful for their decision to hire a surveyor who laid out the first planned city west of the Alleghenies. He laid out a city of public squares and a promenade reserved public use.

Memphians are forever grateful for their decision to hire a surveyor who laid out the first planned city west of the Alleghenies. He laid out a city of public squares and a promenade reserved public use.

Looking back 204 years, it seems a stretch to suggest that the three founders of Memphis were motivated by a bold civic vision inspired by a commitment to green space while pricked with a civic conscience to define a great city.

In short, they were businessmen, looking to buy some cheap land and sell 362 lots as quickly as possible, take their profit, and move on to other real estate projects.

They never lived in Memphis and instead left one of their sons, Marcus Winchester, to remain to look after their investment. It wasn’t easy as the new city was overrun by drunk boatmen and its importance was outstripped by Raleigh, which was designated as county seat and had the largest population in the new Shelby County.

Founders Working For Themselves

The issue that sparked conflict and controversy in the 1820s and 1830s was the question of the Promenade. One court in 1834 ruled that the City of Memphis had the right to use or dispose of the land as it chose. The historical record suggests that the founders may have been motivated by a desire to maintain a monopoly with little regard for the interests of the few hundred residents of the founders’ land venture.

“Yet the issue which engendered most hatred between inhabitants and proprietors was the question of the Promenade,” wrote Tulane University history professor Gerald M. Capers Jr. in his definitive book, The Biography of a River Town.

”The original agreement stated that this tract was donated as public ground to which the proprietors relinquished all claims for themselves and their heirs, ‘but all other rights not inconsistent with the above public rights incident to the soil it was never the intention of the proprietors to part with, such as keeping a ferry or ferries.’”

He writes: “Overton contended that the owners had not surrendered their ferriage, wharfage, and other riparian rights by the donation – in fact, he declared that he had been of the opinion, even prior to his purchase of the Rice tract in 1792, ‘that someday the water privilege attached to the banks would be worth more than all the lots.’”

The historian concluded that Overton, in his actions, was “undoubtedly attempting to preserve a monopoly on the river front, though from his actions his immediate objective is not always clear.” Although Mr. Capers wrote that it was Overton who deserved the credit for making the city because “no matter was too petty for his attention,” the behavior contributed to the persistent animosity between the founders and residents that has been chronicled by historians.

“It must be said that Overton’s motivations do not seem to have included any concern for the welfare of the people or the future of the country, but to have been the mere desire for accumulation of wealth. In his nature, there was not an iota of magnanimity or generosity; if he rendered a trivial service to Jackson and Winchester, his closest friends, he, the richest man in Tennessee, demanded his pound of flesh. Working for Memphis, he was working for himself and that was the limit of his horizon.”

Anomalies of History and the Present

It is a historical context regularly ignored in the history of the majestic Promenade. It does not mean that however it happened, the people of Memphis should not celebrate the fact that a promenade was preserved for public use from Market Avenue to Union Avenue and from Front Street to the Mississippi River.

That said, it is an anomaly of Memphis history that more than two centuries after the city’s founding, its slave-owning White founders continue to grip decisions in the majority African American city that now exists.

That a group which says it is committed to protecting the special natural asset that is the Promenade is fighting to put more concrete on it is yet another anomaly of this dispute.

Then, too, the lawsuit is signed by three heirs of the founders – two related to Overton and one related to Winchester – and it is unclear if they are suggesting that they are speaking for the hundreds of other heirs. Five years ago, an Overton heir living in Nashville told Daily News’ Patrick Lantrip that more than 50% of the heirs believed City of Memphis should make decisions about the Promenade rather than the heirs.

In the end, the questions about the Promenade represent 200 years of facts and fiction but this much will be clear: the chancellor will not be moved by emotional, over-the-top arguments and claims but instead, she will be searching for the place where reason, fairness, and equity converge.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.