By John Branston

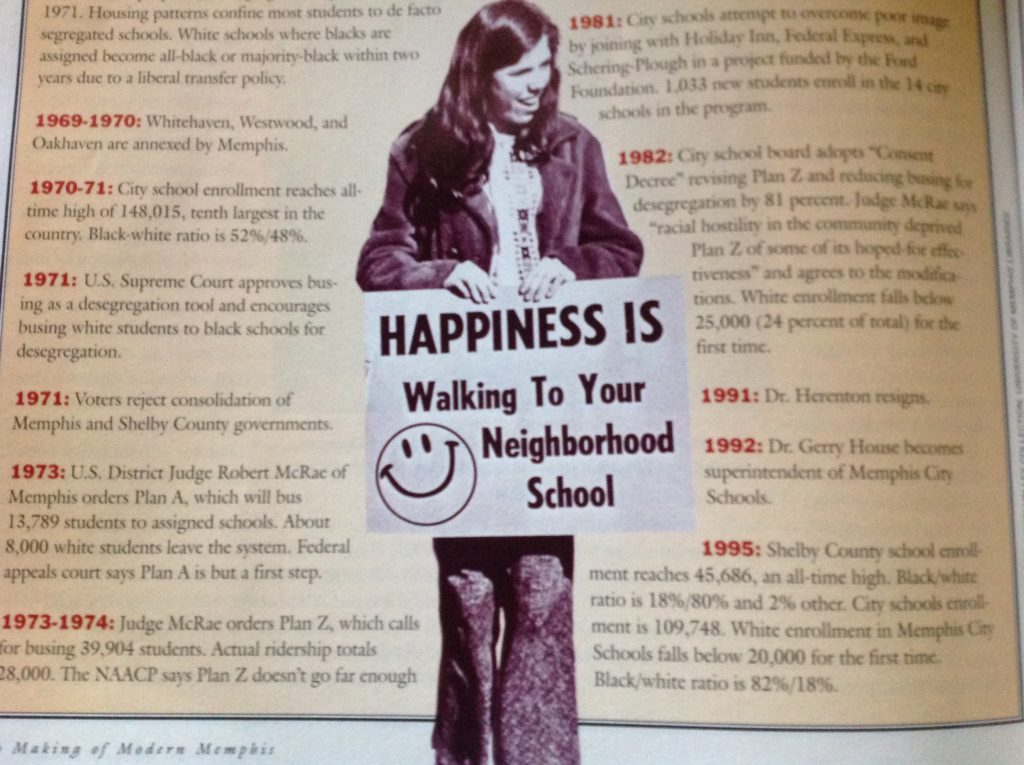

There are not likely to be any celebrations or official proclamations, but this is the 50th anniversary of White flight, the force that, as much as the King assassination, the yellow fever epidemic or the great flood changed Memphis forever and made it what it is.

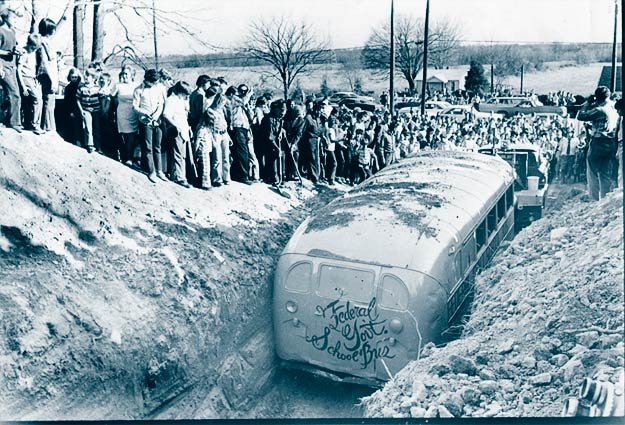

The guidepost was the Constitution. The short name was Plan Z. And the iconic picture shows a bunch of white people burying a school bus.

In 1971, Memphis had the tenth largest public school system in the country – 148,015 students, all but perhaps 100 attending one-race schools. Desegregation had begun in 1962 with a grade-a-year plan that sent a handful of brave Black students to all-White schools. It was slow, and federal judges here and in other large cities took note and tried a different approach. The theory, which now seems hopelessly naive, was that parents and children would willingly abandon their neighborhood schools for an ideal.

Here are some of the key players in the story which is still unfolding.

Deborah Northcross was the plaintiff in Northcross vs. Memphis Board of Education, a lawsuit filed by The Legal Defense Fund in 1960 represented by Thurgood Marshall, later a U. S. Supreme Court justice. Dr. T. W. Northcross was a dentist whose daughter was eight years old. At the time there were 53,142 white children and 42,061 Black children in the system.

Deborah Northcross graduated from Central High School in 1969.

“Desegregation gave Whites the impression we wanted to be with them, and that was not the point,” she said. “It was a matter of school choice and educational equity.”

Mchael Willis was one of the 13 students who integrated the schools in 1961. His father was a well-known Memphis lawyer and co-counsel in the desegregation lawsuit. Michael went to Bruce Elementary and came to school and was driven home in a Cadillac. He was not just called “n—–,” he was “rich n—–.”

He was already going to his neighborhood school when he transferred to Bruce.

“Deep down I wish it had not happened to me,” he said. “I have three children myself, and going to first grade in a loving environment is so important. I was just not on a solid foundation. It made me more reserved as a person, more defensive, and never sure if I was doing the right thing.”

He later changed his name to Menelik Fombi.

The Memphis NAACP under the leadership of Maxine Smith was involved in school desegregation at every critical point in the story. She helped recruit the 13 students (later 12 after one returned to his old school) who broke the color barrier. The violence at Little Rock in 1957 was fresh on everyone’s mind.

“I bet we went to 200 houses trying to get volunteers,” she said. “It was difficult to persuade the mothers that this was good for their kids.”

Fast forward now to the 1970s.

Robert McRae, himself a product of Memphis public schools, was the federal judge who wrote the busing order. In 1973 Plan A ordered the busing of 13,789 students; some 8,000 white students left the system. A federal appeals court ruled that Plan A was “but a first step.” Next up was Plan Z calling for busing 39,904 students although only about 28,000 actually participated. Another 20,000 students left the system, many going to pop-up private schools with a church affiliation.

“I tried to stop with Plan A but the appeals court wouldn’t allow that,” he said. “I was disappointed in the reaction to Plan A.”

It is often overlooked that Plan Z was unpopular with Blacks too. The NAACP wanted 60,000 students bused and called it a “grotesque distortion of the law.” A total of 26 inner-city schools were never integrated either because there were not enough White students to go around or because planners did not think anyone would go to them.

O. Z. Stephens was the man who wrote Plan Z. McRae came up with name. He could be sharp tempered and did not want to run the alphabet with a succession of plans.

“Inasmuch as my middle initial was Z, I got tagged with it,” said Stephens. “My identification with Plan Z killed me professionally in the school system.”

Nevertheless, he called McRae “ a profile in courage” for not booting the case to the appeals court. His son, David Stephens, was a prominent player on the suburban side during the surrender of the Memphis City Schools charter ten years ago. He is superintendent of the Bartlett schools and was named Tennessee Superintendent of the Year in 2016.

James Paavola was Pupil Services director for MCS in 1973 and rode the buses that year.

“Parents were worried to the point of tears at putting their children on crosstown buses,” he said.

Louis Lucas was one of the civil rights lawyers at the center of the busing cases. He believed systematic segregation did not go away after Jim Crow laws were struck down but were the product of neighborhoods and school attendance zones drawn by a Whites-only school board cozy with realtors and the mayors.

“Plan Z eliminated a basic structure of White and Black schools in large areas of the city,” he said. “It left a block of schools untouched. But to say the whole plan was a failure is to ignore gains I think have been made in both perception and actual interaction of children in the schools.

“Plan Z eliminated a basic structure of White and Black schools in large areas of the city,” he said. “It left a block of schools untouched. But to say the whole plan was a failure is to ignore gains I think have been made in both perception and actual interaction of children in the schools.

Lucas lived in Germantown and his daughters attended county schools.

“We didn’t move out there for the schools,” he said.

Karen Champion was a Spanish teacher at Central High School in the 1990s and graduated from Hamilton High School in Whitehaven in 1967. Central is an optional school that attracts college-bound students as does White Station High School in East Memphis.

“Our games were packed when I was at Hamilton,” she said. “Now unless the team is great it’s difficult to get fans. When kids don’t live in the neighborhood and can’t walk to games there is not as much loyalty to the school.”

Willie Herenton was a teacher and administrator in Memphis public schools, an outspoken proponent of racial justice and equity, and superintendent of MCS before becoming mayor. Arguably, he is as responsible as anyone for the creation of the Memphis optional schools program designed to keep some White students even at the price of hurting Black schools by poaching their best and brightest.

Virginia Burnette and her husband Ken, a minister, moved to Memphis in 1968 and kept their children in public school (Melrose and Overton) after busing began. She remembered 1973 as “the most tumultuous year of my life.”

“No one, including me, thought busing would ever actually take place even though church meetings, private parties, and lunch gatherings eventually got around to talking about it. Most of my friends were also members of our church so the conversations included my husband’s and my understanding of integration as a Christian value. To say there were differences of opinion is an understatement. Most of us believed that we were doing what God would have us do regardless of the choices we made. One woman told me she believed God had sent her some extra money she could use for her child’s private school tuition. Ken and I believed with all our hearts that choosing to allow our girls to participate in busing would be the beginning of real equality for all children. It was a terrible time for everyone. Much of our anguish was that our daughters were the ones who were going to have to actually live out our commitment to equality.”

**

John Branston did these interviews while working for Memphis magazine and The Memphis Flyer. A longer version is in his book Rowdy Memphis.