In a city with one of the lowest ParkScore ratings in the U.S., it’s no wonder that so many Memphians are passionate about the loss of precious parkland to zoo parking in Overton Park.

Essentially, the casual disregard shown to the greensward over many years is evidence of a decades old attitude that puts little importance on parkland.

The results of that attitude reverberates in Memphis’ dismal park rankings.

That the people fighting to get the zoo parking lot out of Overton Park are still subjected to gratuitous comments by television commentators and in television coverage says much more about television news than about the protesters. After all, the coverage and commentaries reflect a lack of understanding about the importance of parks in the life and future of cities.

As is often the case, the coverage and commentaries demonstrate television’s tendency to see things as personality conflicts, horse races, and winners and losers rather than to shine a light on the substantive issues and policies that underlie the news headline.

Tale of the Tape

Here’s the headline for the cities’ park rankings: Memphis ranks #85 out of 100 cities. The ranking takes into account park acreage, spending on parks, types and numbers of facilities, and accessibility.

Here’s the tale of the tape: Memphis has 9,145 acres of parkland, or 4.7% of city’s total size; median park size is 10 acres; park spending per resident is $53.09; 2.9 basketball hoops per 10,000 population; 0.5 dog parks per 100,000 residents; 0.9 recreation/senior centers per 20,000, and only 41% of the population is within a 10-minute walk of a park.

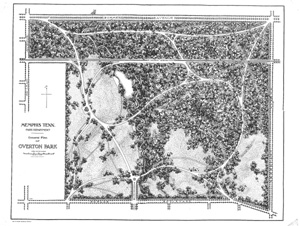

Memphis most-visited park is Overton Park, and its largest park is Martin Luther King Riverside Park.

Of the four indicators that make up the ParkScore, Memphis scored 23 out of 40 points on acreage; 5 out of 20 points on investment; 8 out of 20 points for facilities, and 9 out of 40 points for access. Memphis’ overall score was 36.5. The lowest score in the rankings was 28 and for Fort Wayne, Indiana, and the highest score was Minneapolis at 86.5.

St. Louis ranks #22, Kansas City and Raleigh tied at #36, New Orleans #41, Richmond #48, Nashville #55, Atlanta #51, and Austin #47.

Headed In The Wrong Direction

The top 10 cities were Minneapolis, St. Paul, Washington DC, Arlington VA, San Francisco, Portland, New York, Irvine CA, Boston, and Cincinnati.

The ParkScore rankings by The Trust for Public Land is widely seen as the definitive indicator for how well each city meets its need for parks.

There was a time, in 2012, when Memphis was ranked #31. Then again, there were only 40 cities in the ranking back them. Unfortunately, as The Trust for Public Land added cities to the ranking, Memphis sank. For example, in the 2015 ParkScore rankings, Memphis was #67, but there were only 74 cities in that comparison. In 2014, Memphis was #53, but there were only 60 cities in the ranking. In 2013, Memphis was #42 out of 50 cities.

We wrote on May 10, 2016 how the decline of parks mirrors the demise of the Memphis Park Commission in 2000 after 100 years of leading park development and advocating for more funding for parks. This report only underscores the impact of that decision.

The To-Do List

In 2014, The Trust for Public Land’s Tennessee Office and its Center for City Park Excellence produced a report that evaluated the current state of Memphis parks and issued recommendations that called for the following:

1) An advocacy group to build a constituency for more funding for parks

2) Elimination of fragmented parks responsibilities with an organizational restructure to unite all park programming

3) The undertaking of a full-scale parks master plan

4) Promotion of an interconnected web of trails and creation of a citywide greenways that links many existing parks

5) Finding the proper balance between public and private funding

6) Undertaking a detailed study of the capital and other needs of the Memphis and Shelby County park systems

7) Identifying a small number of existing parks that can serve as nodes for quality smart growth redevelopment that in turn uses the fiscal gains from the redevelopment to improve the parks.

The Canary

“While Memphis has an accumulated legacy burden from city expansion, park underfunding, unimplemented plans from the past, and other challenges, it also has many recent accomplishments that have energized the city’s park lovers and drawn national attention,” the report said, calling out the Overton Park Conservancy. “Because of this, there is an upwelling of interest by advocates, funders, and other city leaders in investing in parks for both their benefits to public health and to the environment and the economy.

“…It is our opinion that the starting point is through a good deal of citizen input, encouraged and enabled by city government. From this input and advocacy, other critical steps can follow, including the creation of a robust park system analysis and a master plan, and potentially, the electoral passage of a major park improvement bond measure.”

It begins by remembering that a great park system does not have to be part of the past, but a driver of growth and prosperity for the future. It begins with the conviction that parkland matters but those are merely words. They have to be followed by decisive actions.

In this way, Overton Park is the canary in the coal mine. If the city’s most visited park cannot provoke the civic will to protect and improve it, the future does not portend well for smaller neighborhood parks.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.

Memphis, like many cities, has our current share of social, financial, and city wide protective problems. But most Memphians are adamant about their appreciation and love of their amenities like Overton Park.

Regardless of what percentages have been projected about about Memphis’s interest in Overton Park, the citizens of Memphis have bonded their support of this most treasured parcel of public property and, I believe are willing to do what is necessary to stand for what they care about.

Overton Park is an asset to the city, but like so many other assets in Memphis it has suffered years of neglect and is poorly managed. The Zoo’s commercial encroachment and the huge parking fiasco are prime examples of its shortcomings.

Overton Park is often a bit ragged with trash in green wooded areas and trash cans are often not emptied for days. Much of the dense wooded areas can seem very sketchy, even during the day. You don’t want to go to those spots much in summer or after school hours because it just does not seem safe. Much much needs to be done to reslky really improve the amenities and safety of the park.

Was Shelby Farms not included? Seems like that would’ve drastically changed the rankings.

Yes, Shelby Farms Park was included.

Our park score ranking is low. So then — what else is new? Like in every other survey or poll, Memphis is among the worst No surprises here. This city just sucks.

Our parks should be an emerald necklace, not an albatross

Anonymous 10:28: When was the last time you visited Overton Park?