Only a few days ago we wrote about the Norris-Kelsey Tax Increase, a likely Shelby County property tax increase caused by a Tennessee Senate committee’s rejection of $1 billion in federal Medicaid money.

Now, we have the Curry Todd Tax Increase, which will likely result from his ill-conceived legislation to void the so-called 75 percent law, which requires Tennessee counties to give public defenders at least 75 percent of the funding given to prosecutors.

In the end, it would cut funding for our award-winning defender’s office that will have to be made up by county property taxpayers. Even more egregious is the fact that it is essentially the state legislature putting its thumb on the scales of justice in a heavy-handed exercise of political interference.

Here We Go Again

Just as the Medicaid decision will drive up the health care budgets of Shelby County Mayor Mark Luttrell, so will this bill because the public defender’s office is another department under his administration. It once again provides a dramatic contrast between Republican leaders who actually have to manage services and operate government and those who have no similar experience and spend their political lives playing to the cheap seats.

Then again, as State Chairman and member of the national board of directors of the America Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), the now infamous bill mill for right wing corporate influence peddling, and as someone who once described pregnant undocumented immigrants as multiplying rats, it’s not as if our expectations for his leadership were high to begin with.

But once again, it calls attention to the chasm that regularly exists between the rhetoric in the Tennessee Legislature about allegiance to conservative values and actions that directly belie those words. In Mr. Todd’s case, he says online that he “believe in tradition, in simplicity…(and that) everyone can help make the world a better place, one step at a time.”

Speaking of tradition, the Shelby County Public Defender’s Office will celebrate its centennial in two years. Back in 1917, when it was created as only the third office kind in the country, Memphis and Shelby County were basking in its reputation as a leader of the Progressive Era with the creation of a public water and gas utility, extension of the city’s revolutionary sewer system, and construction of a system of parks (Riverside, Forrest, and Overton Parks) and boulevards (the Parkways) uniting the city.

Really Conservative Principles

At the time, the group driving progress was a group of corporate leaders who established the Greater Memphis Movement to back the promotion of a progressive civic agenda. It was in the wake of this burst of civic spirit and pride that the Shelby County Public Defender’s Office was formed. In other words, it was a time when cotton was still “white gold,” when women would not get the right to vote for three more years, when Boss Crump was building his political machine, and when Memphians looked down on Atlanta as a Southern pretender.

And yet, those enlightened conservative leaders understood that if they were to take the U.S. Constitutional mandate to “establish justice” seriously, they had the obligation to create a system that provided legal counsel for the accused.

For decades, the office was a point of pride for Shelby County Government, and as recently as the 1990s, it was one of county government’s prime bragging points. This is not to say that the public defender’s office was not frequently treated as “a red-headed stepchild at a family picnic,” in the words of a county commissioner back then who was concerned about the disparities between the budgets of the Shelby County Attorney General’s Office and the Shelby County Public Defender’s Office.

Concerns by former Commissioner Jesse Turner were motivated by the fact that the public defender’s office had to scratch for every dollar it got while the prosecutor’s budget climbed year after year with few questions asked.

There was even a move by the board of commissioners to reduce funding for prosecutors on the basis that they are employees of State of Tennessee while money was needed for public defenders who are Shelby County employees. For a time, there was a resolution that stated that as assistant attorneys general retired, funding for the prosecutors’ office would be reduced, but as it often has done (the state attorneys general association’s shameless fingerprints are on the Todd bill), the attorney general’s office made any suggestions about reducing its budget as being soft on crime.

As a result, the growing budgets with more and more county money to subsidize state employees in the prosecutors’ office was called “one of the biggest bait and switches in our history,” in the words of another commissioner.

Out of Order

But opposition to Mr. Todd’s irresponsible bill should be about more than tradition. It should also be based on efficiency, because reduced future budgets for the public defender’s office could likely mean that more people are jailed at costs that are astronomically more expensive than the programs for which the Shelby County PD’s office has received national awards.

Mayor Luttrell, a former sheriff and corrections professional, has high praise for his appointee, Chief Public Defender Stephen Bush, who designed the nationally significant Jericho Project, a national jail diversion model for detainees with serious mental illness and substance use disorders. This program is good news for beleaguered county taxpayers because interventions are much less expensive than the cost of incarceration, and because continuing to jail mentally ill people and addicts is the antithesis of any meaningful definition of justice.

Justifications for the Todd bill by Shelby County District Attorney General Amy Weirich were thin and self-serving to say the least. The attorney general is the proverbial hammer who sees every problem as a nail, and the nail in this case is always more money to pay for more prosecutors and longer sentences. The idea that only the prosecution side of the court system needs budget increases while defense budgets languish is misleading in the extreme.

But, the notion that this imbalance in the justice system should now be sanctioned by the State of Tennessee is nothing short of arbitrary and capricious, a fact made even more serious because it comes at a time when our local attorney general’s office is suffering from a loss of public confidence as a result of egregious, unprofessional behavior that calls into question its commitment to fundamental fairness and the rules of criminal procedure.

While there is never a good time to change the state’s 75 percent law, to do it at a time when the public defender’s office is a much-needed watchdog for fairness in the criminal justice system makes this bill especially intolerable.

Savings Money and Lives

We live in a region where the incarceration rate is about 80 percent higher than the Atlanta region, more than three times higher than Birmingham region, two times higher than Baltimore, four times higher than Detroit, and two times higher than Chicago, St. Louis, Washington, D.C., and New York City. The “lock ‘em up and throw away the key” philosophy is financially unsustainable and drives up the tax rate, it puts too many people in jail, it neglects the fact that there are proven, and it criminalizes behaviors of the mentally ill and addicted.

But the financial costs pale in comparison to the human costs of tens of thousands of lives that could have been salvaged by a system as intent on rehabilitation and restorative justice as punishment and incarceration.

The reality of restorative justice in Shelby County is outstripped by the rhetoric about restorative justice, and if the State of Tennessee wants to do anything to help our system of justice, it should provide targeted funding for Memphis and Shelby County to experiment with more restorative justice programs and expand the programs under way.

It’s A Constitutional Right

Today, in Shelby County, the budgets for criminal justice from arrest to incarceration is an industry that costs taxpayers about a half billion dollars a year. There are better ways to invest this tax money, and the public defender’s office has led this movement for smarter criminal justice more than any other area (and this certainly includes the attorney general’s office).

Already, the public defense system in this entire nation is in a desperate state. Repeated studies have shown that enormous caseloads and underfunded offices threaten the Constitutional right to counsel established by the U.S. Supreme Court in the unanimous Gideon v. Wainwright decision in 1963.

If the attorney general thinks that she has a tight budget, she should try fulfilling the responsibilities of the public defender’s office with its budget. If she believes that her prosecutors are underpaid and that there are too few of them, she should try to guarantee the right to counsel with the public defender’s salaries and staff. If she believes that her office deserves preferential treatment and that the public defender’s office doesn’t deserve fair play, she is not merely mistaken, she is misguided.

Perhaps, Mr. Todd and many of his fellow legislators have been lulled into a law and order mentality by the powerful Tennessee District Attorneys General Conference lobby, but make no mistake about it, the Todd bill is a direct assault on a cherished American value – the right to counsel, it threatens the promise of equal protection under the law, and it should receive the result it deserves – defeat.

It’s critical to remember the connections among systems in Shelby County and the role they play collectively to determine what happens here in the lives of children and families in or near poverty.

The decisions being made are essential to making sure systems continue to produce the outcomes they are designed to produce but more efficiently. In this case, efficiency means spending less money on things that slow down the desired results.

I recently wrote an essay on school discipline policies, the precursor to the mass incarceration of Memphians. black men especially.

Read it here: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/teaching-children-who-adriane-williams

If the public has a right to adequate prosecution, then individuals have a right to adequate defense (a la Gideon). I say Public Defender’s office should be funded at 100% of Attorney General’s office, and the State of Tennessee should pay for it, not Shelby County.

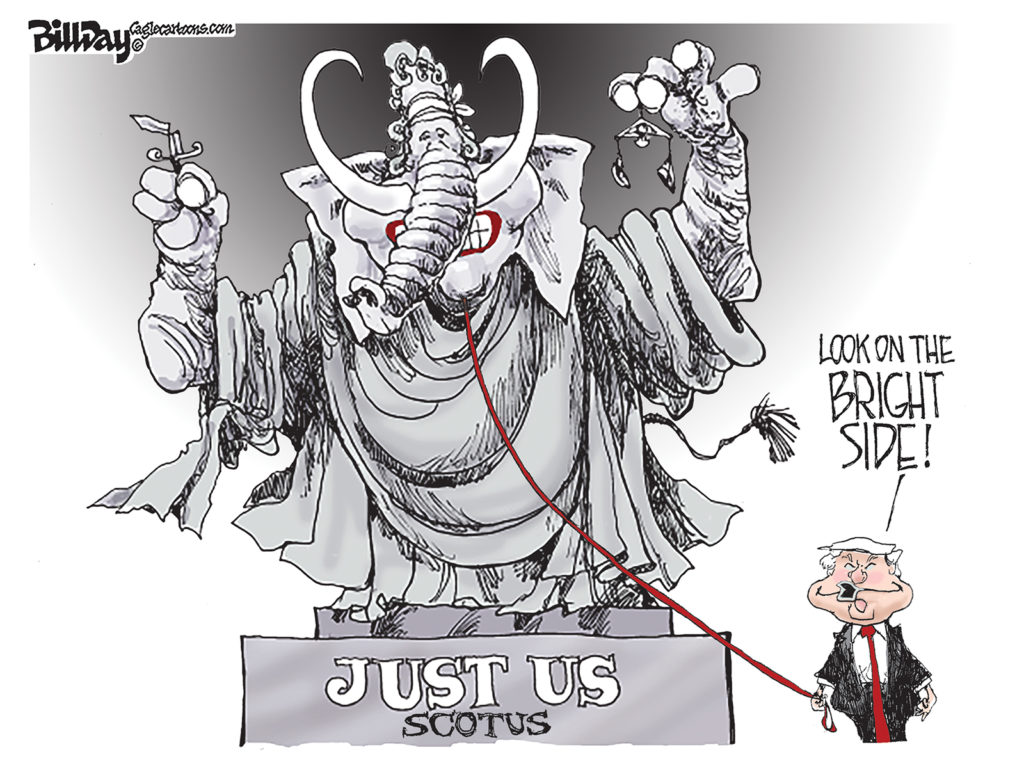

The Republicans seem (like C. Toad) to be more Fascist (authoritarian right) than any other label one could hang on them. They want to control everything they touch, but they can’t see their ways. They think they are patriots but really are like Bill Day’s cartoon this week.

I’m sorry. I misspelled Curry Todd’s name.