“Every system is perfectly designed to achieve exactly the results it achieves.”

Dr. Don Berwick may have been talking about the health care system, but he could have just as easily been talking about economic development in Memphis. Repeatedly, we act as if our economic challenges just happened or were driven by forces beyond our control. And yet, our economic development strategies are perfectly designed to achieve exactly the results they achieve. Unfortunately.

As if often the case, the people who should be sending up warning flares are too invested in the current system to be objective or honest. Maybe it’s our own fault. We seem unprepared to tackle the really tough problems before us, so we pay people a lot of money to lie to us about the state of things.

Hard Facts

In recent posts, we’ve spotlighted data that should tell us that we have to shake all vestiges of business as usual.

To recap, we lost 17,700 jobs in a recent 12-month period, and since March, 2001, we have lost 34,700 jobs, or an average of about 1.5 a day for nine years.

If that’s not enough, in a 10-year period ending in 2007, Shelby County lost 49,000 people and $1.9 billion in income.

To our way of thinking, either of these would be reason enough to declare a crisis and call all hands on deck to address it. But there’s more.

Hiccups

The Commercial Appeal reported today that total personal income in our MSA has steeply fallen to below 2007 levels. Per capita income for 2009 is $37,495, compared to $38,050 in 2007. Total personal income since 2007 is now at $48.9 billion, $200 million less than 2007.

If we were waiting for shock therapy to jolt us out of our lethargy, surely the combination of these three facts should do it. And yet, economic development officials, according to CA reporter Wayne Risher, believe it’s a “hiccup in their job creation efforts.”

It raises the question: What job creation? It’s tempting, we’re sure, for our economic development officials to treat the current problems as merely the symptoms of the global recession that erased $13 trillion dollars in wealth, but that would be oversimplifying things.

The problems facing Memphis go back a decade, and faced with a changing global economy, we continued to pursue low-wage, low-skills jobs, we failed to invest in workforce training and talent, we acted like a company town whose future rested with one international corporation, and we did little to cope with changing times.

A Deep Hole to Fill

In other words, perhaps we can give people a pass for the economic tumult of the past 18 months, but it’s hard to ignore almost a decade of declining fortunes that never led to questions about a “full steam ahead” approach.

John Gnuschke, the authoritative University of Memphis economist, put it accurately. “We’re a struggling community to begin with, and a 2.3 percent loss is pretty serious to us,” he said. Some days, it seems that only members of the Sparks Bureau of Business and Economic Research at U of M are willing to tell it like it is, and that’s a shame. As long as so many people participate in the charade that we have a plan that will turn things around and that once the economic turns around, we’ll be in good shape, we are speeding down a dead-end street.

When the jobless recovery does end (some say it won’t for five years) and even when that happens and jobs are created again, we start at least 34,700 jobs down and we probably need another 100,000 jobs or so to mount a serious turnaround.

It’s a tall order, and it will require us to get on the leading edge in economic development theory and planning. More than anything, this requires new people in the room to talk about success in the new economy, new ideas to build on what we are first, best and only in, and new ways to build a city known for its quality, not for its cheapness.

Commodity Trap

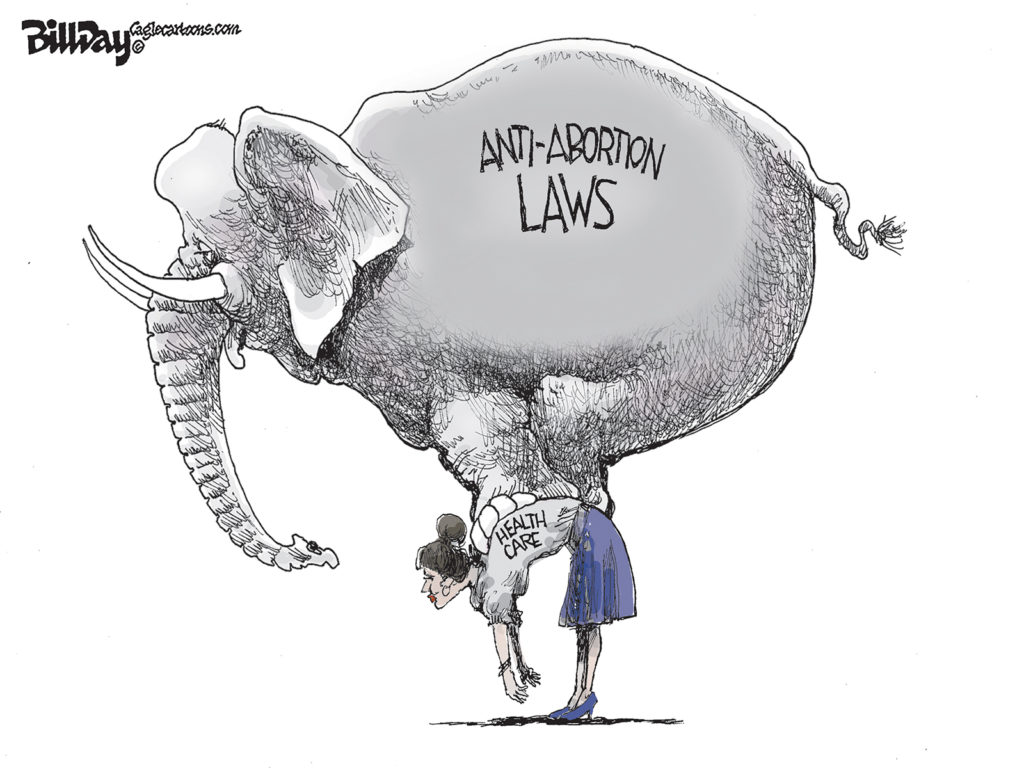

Our economic development strategies are caught in the commodity trap, stemming from our background as an agricultural center and continuing with our emphasis in being a distribution center. Our experience is in selling products that tend to be seen as commodities, to a consumer making a decision based on the lowest price.

Commodity economic development is premised on the same thing – appealing to companies who make their decisions based on the lowest prices. This kind of economic development is forever in a race to the bottom to offer the cheapest land, and the cheapest workers.

Because our tradition is in businesses with thin profit margins, our economic development culture is one with an aversion to risk-taking, which in turns undercuts innovation and entrepreneurship. Cities with commodity mentalities think they can grow their economies with low wages, low land costs, low utilities, low taxes.

That’s because in a commodities world, these are seen as the factors that must be controlled to keep prices down. They are often cited as justification for the tax abatements that we hand out to any company that can complete the form.

New Ideas Needed

Most devastating of all is that cities that are accustomed to a commodity approach to economic development are at a huge disadvantage in attracting and retaining knowledge economy workers. It is not merely a coincidence that companies like FedEx report constant problems in attracting young, mobile, highly-educated workers to Memphis and convincing executives of International Paper to move from the Northeast to Memphis has met with similar hurdles.

Rather than make the investments in the intellectual infrastructure that we need to complete for knowledge-based companies, Memphis continues to sell the infrastructure of the industrial age, at the same time that its last remnants are vanishing before our very eyes.

What is needed are new approaches to economic growth – approaches like economic gardening which focuses on existing entrepreneurs rather than corporate relocations, on biological models of business and entrepreneurial policy and new economic theories and philosophies.

Selling Down

The words of a specialist in economic gardening seem especially especially pertinent to Memphis:

“There was another, darker side of recruiting that bothered us. It seemed to be a certain type of business activity – the branch plant of industries that competed primarily on low price and thus needed low cost factors of production…cheap land, free buildings, tax abatements and especially low wage labor. Our experience indicated that these types of expansions stayed around as long as costs stayed low. If the standard of living started to rise, the company pulled up stakes and headed for locations where the costs were even lower. This was the world when we proposed another approach to economic development: building the economy from inside out, relying primarily on entrepreneurs.”

The race for economic growth in the future will be the hardest competition Memphis has ever been in. But we begin by abandoning the old and embracing the new. It’s a race to the finish, and cities that compete by the same old rules have already lost.

You are 100% correct Smart City. Memphis is at a point were it needs to invest more into home grown entrepreneurs and into its college system.

BINGO!,

Now, what should we build here?

What would benefit people outside Memphis and benefit the inside of Memphis even more and yet still have an appropriate price-tag?

What is called for?

What product is about to be really really needed, well, already is, but not supplied here even though we already have the industries, labor, and facilities here to pull it off, yet underutilized?

Hmmm what would that be? Hmmm, I wonder?

A potent dose of medicine. Nice work.

You’re right, activity is not the same as action, and it takes courage to look beyond caretaking to investing in a future that’s coming anyway. I hope your officials, and their supporters, can do so.

I don’t ever buy into “courage to invest in a future that’s coming anyway”.

Hell, you could just wait for it to get here, and of course, the results garnered for just waiting or investing in a “perceived inevitable” are the same as we have been getting because that is what we already do, that is the definition of just activity.

To get great results beyond what we’re historically known for, you have to choose and design a future based on NOTHING.

Otherwise, you get the second, third or fourth banana future. It ain’t worth having, you learn nothing new that way.