In observance of the Memphis Bicentennial in May, 2019, we will feature regular posts about Memphis as it moved toward its founding and the slow progress it made afterwards. We begin today with a prologue for the years before the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff attracted the attention of three Middle Tennessee developers, Andrew Jackson, John Overton, and James Winchester.

Preface

We all know the story. Memphis was founded in 1819 by Andrew Jackson, John Overton, and James Winchester, who, standing on the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff of the Mississippi River and looking at the untamed river and wilderness before them, they foresaw a city of greatness. They named it Memphis after the legendary capital of Egypt located on another great river, the Nile.

That is the romanticized version about Memphis’ founding but it is apocryphal.

The three prominent Middle Tennesseeans – Jackson was former Tennessee Senator and Supreme Court justice, soldier and future seventh president of the United States; Overton was Superior Court Judge; and Winchester was American Revolutionary War commander – bought the land they would lay out as the town of Memphis but likely never visited Memphis at the same time.

Indeed, Jackson may have only visited the city three years after its founding (if then), and Overton did not travel to assess his investment for several months after its founding. This was not for lack of interest because their correspondence about Memphis was frequent, but because the journey from Nashville to Memphis was arduous and circuitous with the most preferred route being 287 miles.

While their interest in Memphis was strictly as a business deal, the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff was well-known to native Americans and explorers from France and Spain.

First People to the Bluff

The history of humanity in the area dates to about 8,000 years ago with the paleolithic Indians, and by 800 CE, the tribes called collectively the Mississippians built a string of towns along the Mississippi River about 40 miles long with the most extreme northern one in the area of the mounds in DeSoto Park. Another just south would be called Chucalissa (which is a Choctaw word the inhabitants of the site would not have understood).

The bluff would be named the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff because it is the fourth such geographic landmark on the eastern side of the river south of the mouth of the Ohio River although its first settlers were not Chickasaws at all but more connected to the Tunica-Natchez tribes. That said, the area, during the time of European exploration, was most identified with the Chickasaws.

Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto, first governor of Panama and governor of Cuba, ventured through the area in 1541 with his beleaguered army and was treated fairly well by the tribes until he demanded 200 men to help him. The Chickasaws burned the Spanish camp, destroyed much of its equipment, and took several hundred hogs and several dozen horses. DeSoto escaped and the location of his contact with these native Americans is still a matter of dispute, but Memphis has been identified as one of the three likely locations. He died in 1542 after either fleeing to Arkansas or Louisiana, ratifying the Chickasaws’ skepticism to De Soto’s claims that he was a sun god.

Spain to France

In the 132 years following De Soto’s appearance, the tribes in the area disappeared for reasons lost to time. In 1673, Jesuit Father Jacques Marquette and Quebec fur trader Louis Joliet passed through the area (although it may have been on a bluff farther north) looking for a route to the Pacific Ocean.

Nine years later, the French explorer Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle visited the area with the intention to protect the fur trade. While taking a few days on the bluffs to hunt, he also built a crude stockade that was named Fort Prudhomme for the armorer of his party, Pierre Prudhomme, who traveled into the woods to hunt but did not return. The stockade was built for protection while the errant member of the party was sought, and after the exploration group moved on, the “fort” was never used again, although La Salle did claim the territory for France. Ten days after he disappeared, Prudhomme was found floating on a raft he had concocted to follow the party.

For years afterwards, various publications referred to the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff as the “Heights of Prudhomme,” and told how the area was plentiful in bear, wild pigeon, deer, wild turkey, and bison. In fact, the bison were so thick “even the most worthless Frenchman can kill one,” said one journal. As late as 50 years before the founding of Memphis, bison were still hunted on the bluffs.

In 1739, Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne, Sieur de Bienville, in 1739 built Fort Assumption on the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff as the French continued their losing war against the Chickasaws. The French had proven no match against the Chickasaws, and its abortive Campaign of 1739 involved Memphis.

Bienville amassed 1,200 Frenchmen into a fort with three bastions facing the land and two bastions fronting the river. This fort is the first historical event that can conclusively be proven to have occurred on the site of the future city of Memphis (although it is possible that the site was near the remains of Fort Prudhomme). The fort was Bienville’s base against the Chickasaws, but after about eight months of disease, bad weather, desertion, and drunkenness, the French called it quits.

France to Spain

That said, the Fourth Bluff was actually controlled by the Chickasaws for decades although they saw it as a place to meet boats and traders rather than as a dwelling place.

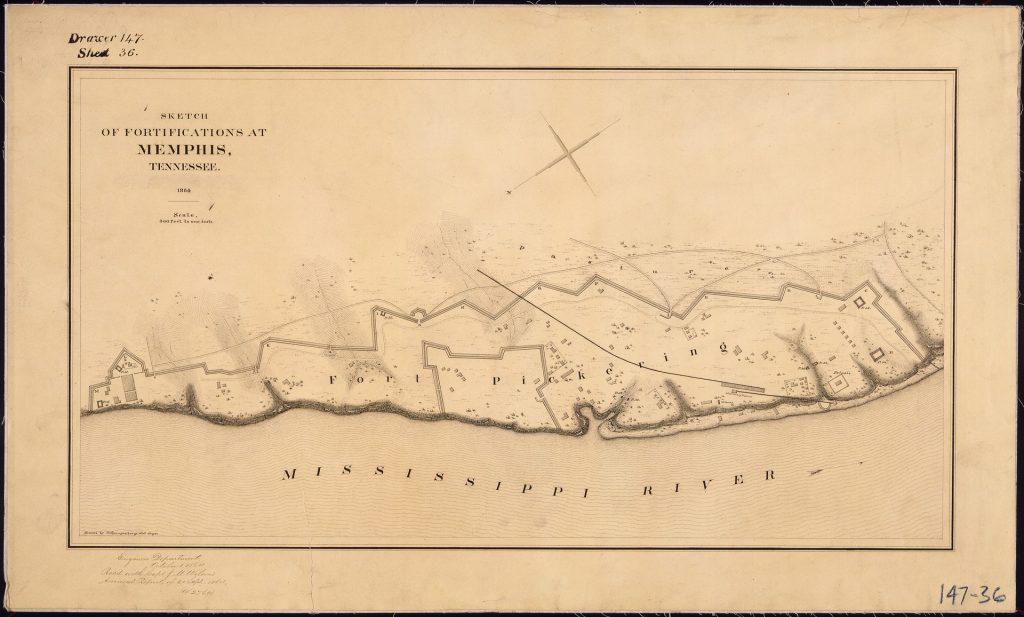

When Spain allied with France against the English in the Seven Years War, its reward was the eastern Mississippi Valley south of Ohio, and in 1795, the Spanish governor of the Natchez District, Dom Manuel Gayoso de Lemos, was ordered to construct a fort at the mouth of the Wolf River.

After paying the Chickasaws $30,000 for the site, the Spanish, who were much preferred by the native Americans to the French, arrived at Esperanza (Hopefield), the Spanish settlement in Arkansas across the Mississippi River from Memphis, and the fort – which was built on high ground south of Bayou Gayoso in the vicinity of today’s Auction Street – had cannons but the barricade was primarily felled trees.

It was more finished by fall, but Gayoso considered the fort as less important than the three boats assigned there to defend the area. From the beginning, Fort San Fernando de las Barrancas (San Fernando of the Bluffs) was a hardship post and its small jail was crammed with soldiers and sailors, and when the fort was scheduled to be razed in 1795 as part of the treaty of San Lorenzo of 1795, it is hard to imagine any protests – although it took the Spanish 17 months to get around to it.

Gayoso had sent Benjamin Fooy, a “Hollander” as agent to the Chickasaws. Frequently called the first permanent Caucasian resident of the area, he cleared some land at the mouth of the Wolf River and planted corn, and when the Spanish left, he moved with them across the river to Esperanza where he maintained a settlement on a land grant from the Spanish (Gayoso named him magistrate and justice of the peace). His brother, Henry, purchased a hut from a native American and cultivated a large farm for several years.

Spain to United States

On July 20, 1797, about 14 months after the State of Tennessee became the 16th state and the first state created from territory under the jurisdiction of the fledgling democracy (the area was previously part of North Carolina), the United States took possession of the Fourth Bluff.

Captain Isaac Guion of the Third Regiment of the Infantry landed with troops and finding Fort San Fernando destroyed, he built a new “sexangular” stockade at the same location although he considered it temporary. It was named Fort Adams and later renamed Fort Pike.

There were four white families in the area who had been there for two or three years, he said.

The American stockade would be commanded until August, 1798, by Captain Meriwether Lewis – he of Lewis and Clark fame and cousin to President Thomas Jefferson – and he was visited during that time by his friend, William Clark, whose name was the other half of the famed expedition to the Pacific Ocean through the continental divide.

Fort Adams was replaced by Fort Pickering, and it was built several miles south of Fort Pike, and for several years until 1809, its commandant was Lieutenant Zachary Taylor, who would become the 12th president of the United States. Fort Pickering remained an army outpost until about 1812.

Next: Development Schemes Give Birth To Memphis

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.

thanks Tom. A much needed history lesson devoid of politics.