When the federal government introduced Opportunity Zones (OZs) as part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the message was wrapped in the language of uplift and equity: unleash the power of private capital to lift up chronically underinvested neighborhoods. Offer big tax breaks (sound familiar?) and investors will rush in to create jobs, build housing, and grow businesses in places long starved of capital.

Nearly a decade later, the program’s uneven outcomes raise questions: Did it deliver for the communities it promised? Or did it primarily enrich those already positioned to profit from tax loopholes? And has the advent of the poorly-named Big Beautiful Bill Act meaningfully changed the equation — or entrenched its flaws?

Opportunity Zones were sold as a market-friendly antipoverty strategy. Investors who roll capital gains into Qualified Opportunity Funds can defer taxes, reduce them over time, and in some cases eliminate taxes on new gains entirely if they hold investments for 10 years. This theoretically encourages long-term commitment rather than quick flips. In practice, it has created one of the most lucrative tax shelters in the federal code—one that disproportionately rewards those who already have significant capital gains to shield.

The first red flag was how the zones were selected.

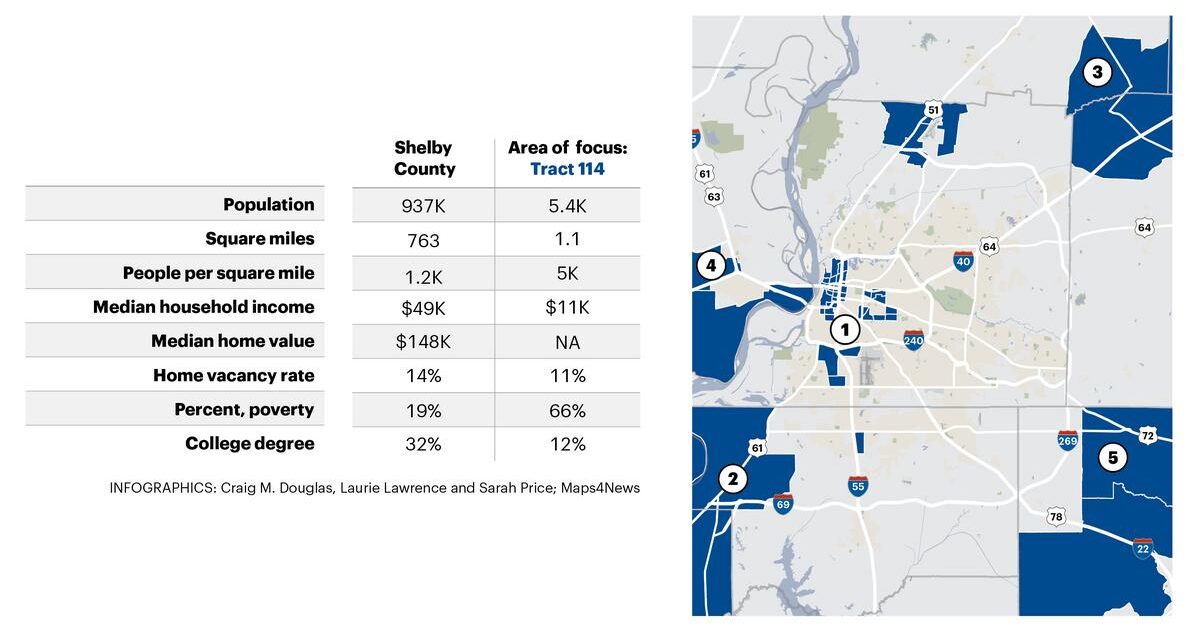

Governors nominated census tracts, and the U.S. Treasury Department signed off. While many tracts were indeed deeply distressed, others were already on the upswing. In cities across the country, maps for Opportunity Zones neatly fit onto areas that were primed for redevelopment anyway—downtown-adjacent neighborhoods, waterfronts, and areas near anchor institutions. In some cases, projects that were already planned or underway were simply restructured to qualify for tax benefits.

It’s Predictable

In many cases, investment has flowed not into struggling small businesses or deep economic revitalization, but into real estate development in areas already on the upswing. Studies from economists at Columbia University and The Brookings Institution concluded that much of the investment in Opportunity Zones has flowed into real estate in areas already experiencing growth. Meanwhile, the neighborhoods with the deepest poverty and weakest market fundamentals often struggle to attract investors, tax incentive or not.

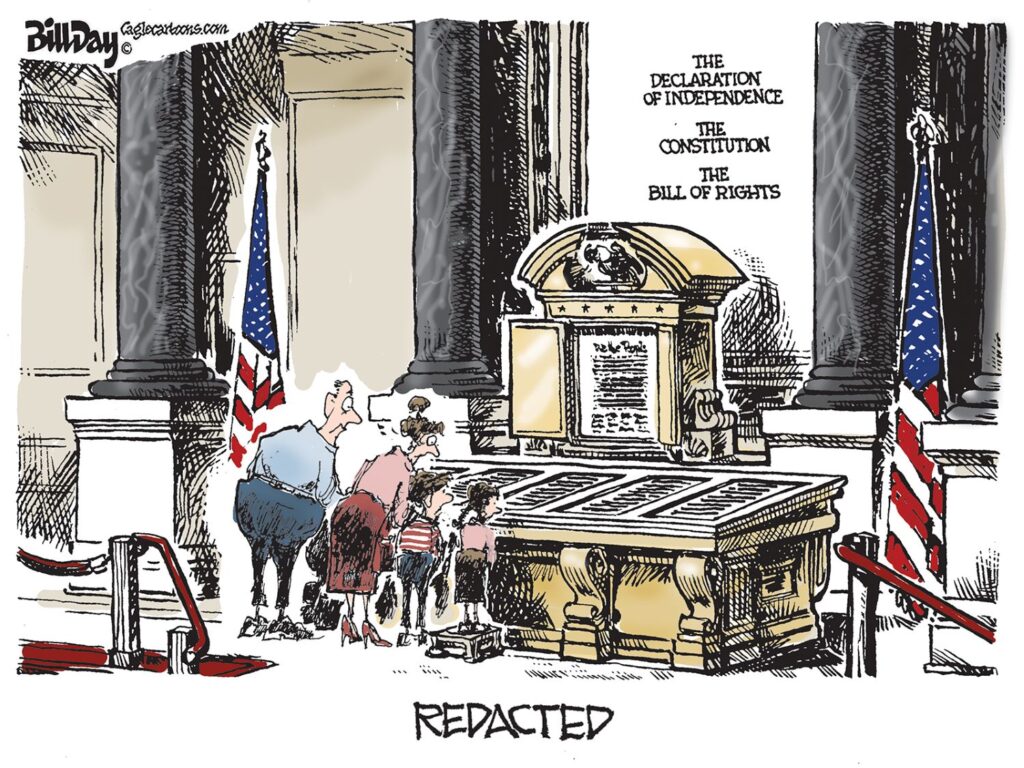

In retrospect, it all seems predictable. The program imposes few requirements regarding community benefit. There are no federal mandates for affordable housing, local hiring, or anti-displacement protections tied directly to the tax advantage. Investors must substantially improve property or deploy capital in qualified businesses, but there is no obligation to demonstrate measurable poverty reduction. Reporting requirements were minimal at the outset, and although Congress later strengthened data collection, the program’s early years unfolded in something close to a transparency vacuum.

The result is that we have a policy framed as community development that operates primarily as a capital gains incentive.

Defenders argue that any new investment is better than none. But Opportunity Zones don’t exist in a vacuum. They represent forgone federal revenue—revenue that could otherwise support direct housing subsidies, infrastructure grants, or proven antipoverty programs (although that’s had to imagine as a goal for the Trump Administration).

The context seems similar to the PILOT program. The question is not whether investment is good; it is whether this is the most effective and equitable way to achieve it.

Where Are Community Needs?

To benefit from Opportunity Zones, an individual must first realize capital gains. That alone limits eligibility to a relatively affluent slice of Americans. According to IRS data, capital gains are heavily concentrated at the top of the income distribution. In effect, the program offers the largest benefits to those with the most wealth, on the assumption that their investments will trickle down into struggling communities.

We’ve seen this movie before. It feels like the Tennessee tax structure, the third most regressive in the country, meaning that the more someone earns, the lower percentage of income that person pays in taxes.

There is also the matter of geographic fairness. Opportunity Zones were capped at 25 percent of eligible low-income census tracts in each state. That meant governors had to choose winners and losers among distressed communities. In some states, political considerations appeared to shape nominations. In others, rapidly appreciating neighborhoods were included alongside deeply impoverished ones, diluting the focus. When the designation itself becomes a political process, it risks undermining the program’s credibility.

The most enthusiastic adopters of Opportunity Zones have been real estate developers and fund managers. That is not inherently villainous; they are responding to incentives and their job is to enhance profits. But it underscores a core tension: the program is structured around investor needs, not community needs. Complex compliance rules and legal structures favor sophisticated players with access to tax attorneys and financial advisors. Small, local entrepreneurs in distressed neighborhoods are less likely to navigate this terrain successfully.

None of this is to suggest that private capital has no role in community revitalization. It does. But capital alone is not a development strategy. Successful neighborhood revitalization typically involves coordinated public investment in schools, infrastructure, transit, and public safety. It requires engagement with residents and attention to displacement. It often demands patience beyond a 10-year holding period.

Big and Beautiful?

Opportunity Zones were born of a bipartisan desire to experiment with a new tool. Experimentation is not inherently bad. But good experiments include clear hypotheses, transparent data, and willingness to adjust when evidence disappoints. So far, the rhetoric around Opportunity Zones has often outpaced the proof.

The promise of Opportunity Zones was that they would unlock hidden potential in places left behind. The risk is that they will instead reinforce an old pattern: generous benefits for investors, uncertain gains for everyone else. It’s yet to demonstrate that the communities most in need are better off.

In July 2025, Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act was signed into law, ushering in the most significant overhaul of Opportunity Zones since their inception. This legislation makes the program permanent and restructures many of its basic features.”

Tax benefits can now be claimed indefinitely, rather than expiring at the end of 2026. Existing zones will be re-designated on a rolling 10-year cycle starting in 2027, and governors will nominate new zones every decade. The threshold for qualifying as a low-income community is tightened, which reduces the qualifying median income from 80% down to 70% relative to area or statewide medians, while eliminating the previous loophole that allowed contiguous higher-income tracts to qualify. The new law mandates enhanced reporting, requiring the Treasury to report annually how much money is invested in Opportunity Zones, how many jobs are supported, and eventually how these designations influence poverty rates and economic indicators.

No Surprises About Motivation

On paper, these changes were meant to address some earlier criticisms: refine targeting, improve data transparency, and broaden investment incentives beyond big urban markets to rural and underserved areas; however, it still operates primarily as a tax shelter for those with significant capital gains to invest.

In simple terms: investors chase the best tax benefit, not the best community outcomes. And thus it shall ever be.

There are stories of new housing units, renovated buildings, and even local job growth. But these anecdotes do not add up to a clear, measurable success story — especially for the residents who are meant to be at the center of the policy’s mission.

The Big Beautiful Bill Act did not dismantle the Opportunity Zone program. It fortified it. It expanded its scale and enhanced its appeal to investors — without fundamentally reshaping the incentives that have produced critics’ biggest concerns. Unless policymakers push beyond incentive carrots and embrace accountability and equity as core policy goals, we risk entrenching a wealthy investor subsidy with mixed returns for the communities that need help most.

For the sake of those communities, and the credibility of federal economic development policy, skepticism must remain firmly grounded and demands for real evidence and accountability should only grow louder.

****

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram for blog posts, articles, and reports relevant to Memphis.