Few things provoke more suspicions than a project that arrives almost fully formed on a public agenda.

And that’s even before it’s said the price tag amounts to $1.3 billion.

That’s the cost of the first phase of a grand plan that builds a new jail and criminal justice building in Frayser at the site of the former Firestone plant.

So much that passes for economic development and public policy in this community are at their base real estate ventures, and without more details and due diligence, this seems to fall into that category.

After all, the plan comes via Cushman & Wakefield, a commercial real estate firm, and was presented by former Memphis City Councilman Kemp Conrad who’s worked there for almost 19 years. While his company has a financial interest in the site, he’s quick to say that the concept could work at other locations.

The plan focuses on the problems of the physical space, but generally ignores the overriding problem at the Shelby County Jail – the culture of the sheriff’s department.

Where’s the Justification?

While there is general agreement that Shelby County Jail is outdated, there remains dozens of questions that need to be answered about the scale and reasonableness of this concept for Frayser. Chief among them is whether each of the elements in the plan – the sheriff’s department training center, sheriff’s offices, Criminal Courts, Juvenile Courts, Civil Courts, Shelby County Corrections facility, Mark Luttrell Transition Center, and Federal Corrections Institute – need new facilities and new locations.

Normally, something of this magnitude would be preceded by a comprehensive feasibility study that determines the condition of each facility and whether its proposed Frayser relocation is fiscally and logistically feasible.

There have been questions for many years about whether downtown is the most efficient location for the jail. After all, regardless of where someone is arrested, police and sheriff’s cars have to transport them downtown rather than to a more centralized location for a jail.

However, there’s not been a definitive analysis to determine the answer to this question and there certainly is no definitive feasibility analysis that concludes that a Frayser location makes more sense.

Then, too, it raises questions about the logic of moving Juvenile and civil courts as part of a giant compound vision. And whether this the criminal justice version of an environmental racism project like xAI, where a majority African American area becomes the site for yet another large-scale development without its residents being asked if they even want it.

Two More Phases To Price

Then, too, it’s worth remembering the proposal has three phases for the 71-acre site, and the $1.3 billion price is for what was described as the first phase – the jail and the criminal courts.

When the Shelby County Jail opened in 1981, it cost $58 million. That’s the equivalent of $202 million today, which begs the question about the cost climbing to $1.3 billion for Frayser.

Then, too, when Shelby County Jail opened, Memphis closed its jail. That raises the question about whether the construction of a new complex in Frayser is a time for Shelby County to tell City of Memphis it’s time for them to again build their own jail. After all, Shelby County is facing another billion dollar project – a new Regional One hospital – so perhaps it’s a good time for it to reconsider its largesse in paying for a jail that houses Memphis inmates.

The layout calls for the relocation of a county prison, a state prison, and a federal prison to Frayser from the area in northwest Shelby Farms set aside for public facilities. The assumption is that county government would not be building these facilities for other government, but the idea laid out by Mr. Conrad was for a lease with an option to purchase.

The suggestion was laid out as a way to keep the cost off its balance sheets but again, there’s no analysis of whether this financing is in the best interest of taxpayers, especially considering that interest rates for the public sector are lower than those for the private sector.

First phase of the plan is for men’s and women’s jails, Sheriff’s Department administrative offices, Criminal Court, General Sessions Court, City Court, District Attorney’s office, Public Defender offices, and Juvenile Court and detention.

The second phase is for civil courts, including Chancery, Circuit, General Sessions, and Probate Court. The third phase includes the sheriff’s department training center, the Mark Luttrell Transition Center, the Shelby County Corrections Center, and the Federal Corrections Institute of Memphis.

Again, why move civil courts to Frayser since there is no synergy of purpose?

Shelby County Sheriff Floyd Bonner is an enthusiastic supporter of a new jail. After all, the existing jail has not worked well since it first opened

Problems From the Beginning

The final fortress-like, monolithic jail and criminal justice buildings characterize our communities’ general disinterest in the architectural quality of public facilities (think Leftwich Tennis Center and Memphis Youth and Special Events Center) and testament to selections of architects and contractors being made through a political process. In the case of the Criminal Justice Complex and Shelby County Jail, it resulted in the selection of architects with no experience in designing jails but important experience as political contributors.

Because of it, the monolithic buildings had issues from their opening days.

The system of pneumatic tubes that was supposed to save time and increase efficiency went on the blink and technology problems surfaced almost immediately but most concerning was the reality that the jail design had heavy personnel requirements – and the attendant heavy labor intensive costs.

Today’s discussion about a new jail echoes former Shelby County Mayor Mark Luttrell’s call for a better facility more than seven years ago. At that time, county government’s struggle with its bonded indebtedness and its associated debt service payments prevented any action along with the reality that the board of commissioners knee jerk opposed most of what Mr. Luttrell pursued.

It turns out Mr. Luttrell was right. The jail continues to house mentally ill individuals, as evidenced by recent photographs of a prisoner in a cell with handprints of feces covering its wall. All county government has done with its delay is to drive up costs and to allow jail conditions to deteriorate. And clearly concerns about bond debt is no less today than they were during the Luttrell Administration, exacerbated by the fact that there are no easy answers for how to pay for a new jail.

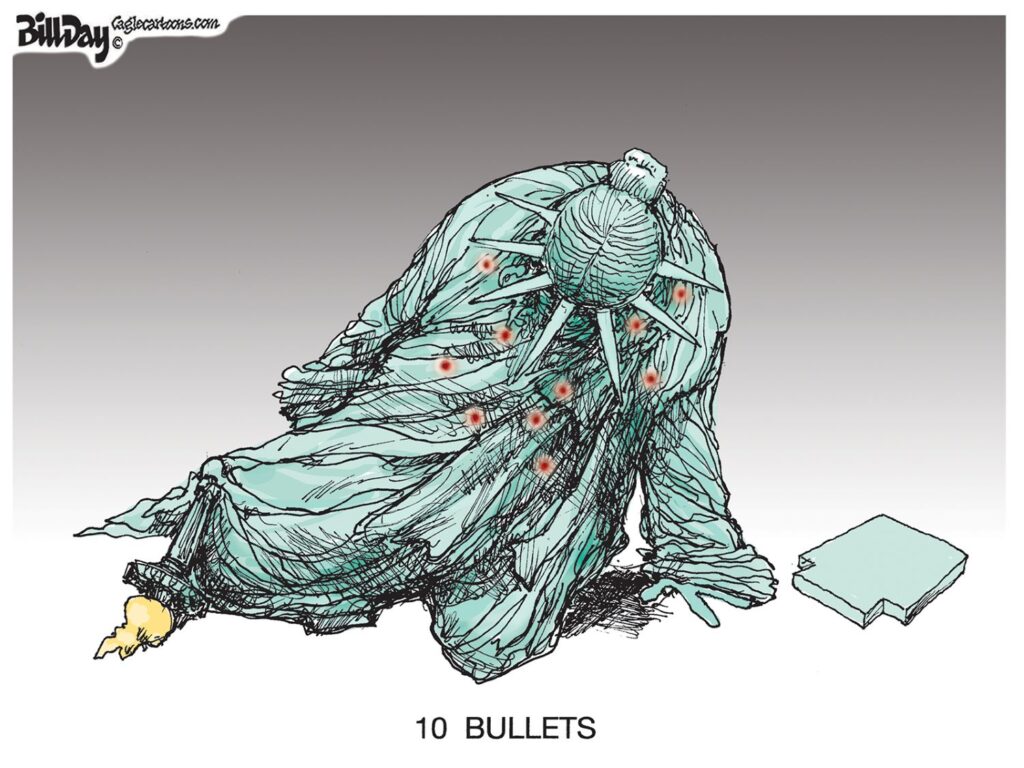

But here’s the thing: it can be argued that building a new jail means nothing if the culture of the sheriff’s department isn’t improved. After all, 64 people have died in the jail since 2019, and this year, there were even four deaths in one week.

It is an intolerable record and the County Board of Commissioners should show much more interest than it has so far in delving into the cultural problems that contribute to the fatalities.

Just City Executive Director Josh Spickler said that the concept for a Frayser concept is “fantastical in some of its assumptions and promises.” He is exactly right and even more correct when he says that the problems in the existing jail will not be solved with a new building.

Just City, the Justice & Safety Alliance, the Memphis Interfaith Coalition for Action and Hope, Stand for Children Tennessee, ACLU of Tennessee, the Black Clergy Collaborative of Memphis, and Decarcerate Memphis have demanded that Sheriff Bonner develop an action plan to improve conditions in the jail and reduce fatalities.

The lack of such a plan suggests that the current culture of the sheriff’s department is incapable of developing one. It’s past time to bring in a national expert who can.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram where these blog posts are published along with occasional articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.