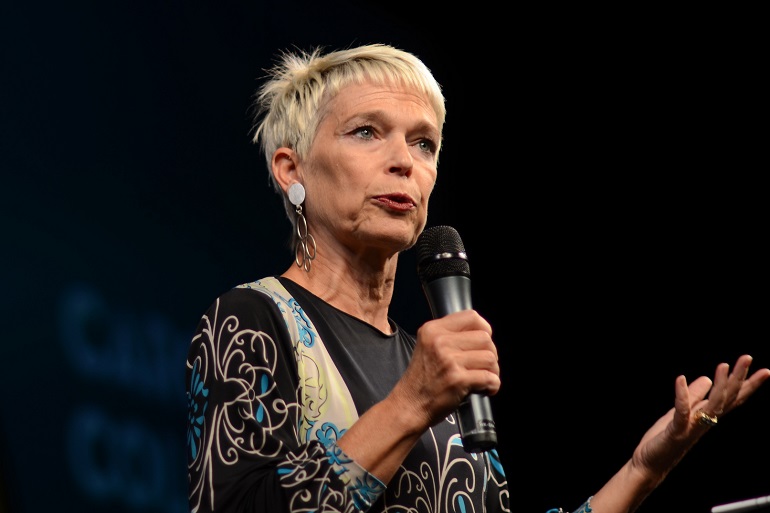

Carol Coletta is known in Memphis as President/CEO of Memphis River Parks Partnership but nationally as one of the country’s most influential urbanists.

As a result, she is often a keynote speaker for regional and national conferences and meetings, but on May 3, she was keynote speaker in her hometown at the International Downtown Association’s 2024 Southeast Urban District Forum. Her presentation drew on her South Memphis upbringing, her childhood love of downtown, her downtown retail store, and 50 years as a downtown residential pioneer. Memphis River Parks Partnership, in only six years, has opened three parks, including the award-winning Tom Lee Park, and brought $80 million to City of Memphis assets without any CIP funds from city government.

Urban planning magazine Planetizen ranks her as one of the 23 most influential women urbanists and #32 for most influential contemporary urbanists. Prior to the River Parks Partnership, she was Senior Fellow in Kresge Foundation’s American Cities Practice where she led the $50+ million Reimagine the Civic Commons, which brought an $8 million grant to Memphis. Prior to Kresge Foundation, she was Vice President of Community and National Initiatives for the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation where she managed a portfolio of more than $60 million annually in grants and a team of 18 in 26 communities.

Here’s her keynote speech:

You’ve spent the last three days exchanging ideas on how to make your downtowns more vibrant, more successful. That’s a journey I feel like I’ve been on my entire life.

I fell in love with this particular downtown very early.

- In fact, my mom and dad met on Main Street where she tinted photos at Silver’s.

- When I was 13, I rode the 13 Lauderdale bus downtown with a friend every Saturday to see a fashion show, hear a band, and walk around this place that was so very different from my own neighborhood.

- By the time I was in high school, I was writing the Mayor telling him what to do with Beale Street.

- During the earliest days of downtown revitalization and just a few years after the civic unrest leading up to and following Dr. Martin King’s assassination, I was selling downtown, first, as an aide to the Mayor, then as the first employee of the CBID – the predecessor to the Downtown Memphis Commission.

- I owned and operated a retail store in downtown for 7 years.

- As an early downtown residential pioneer, I’ve had my home in the heart of downtown Memphis for almost 50 years, even while also living in downtown Chicago for almost a decade and in downtown Miami.

- Now, I have the great honor to lead an organization that is bringing our magnificent riverfront adjacent to downtown to life.

Thank you for the work you do and the care you give to what I believe is the single most important place in any community – our downtowns.

Call them what you will – center city, uptown, the central business district, the central social district, business improvement district or some name one of you in this room is probably coming up with right now – everyone in this room understands why downtowns are so important to the success of our cities.

Downtowns – whether we like it or not — define our cities.

- They telegraph a city’s ambitions not only to visitors and prospective investors, but also to locals, even if they never visit.

- Downtowns are historically big generators of local tax revenue.

- They are typically our communities most walkable neighborhoods, the only hope most of our cities have for a 15-minute neighborhood.

- They serve as shorthand on a city’s character… what is authentic.. what the city values.

- Downtowns are critical social infrastructure… often the only place we regularly come face to face with people whose backgrounds and circumstances are wildly different from our own. They teach us how to do democracy.

- And downtown is the place where the community comes together to celebrate civic wins. No one group owns downtown because everyone owns downtown.

COVID was really tough on downtowns. All of us who work so hard to make downtowns live up to their potential…. their imperative … have been frustrated by the too-slow return of people to offices, to live entertainment, to dining out. Add concerns about crime, car chaos – amplified by social media and local TV news – the fickleness of many U.S. business leaders and their relationship to local communities, and the presence of the unhoused on downtown streets, and it’s made a tough job even tougher.

Fortunately, Downtowns are coming back – just as they did after 1968 and the crash of 2008. But, as they come back, they will come back as something different.

In his book, The Triumph of Cities, Ed Glaeser writes about the enduring strength of cities like New York, Chicago and Boston resulting from their ability to adapt and change.

That is our work today: to make sure our downtowns are adapting to changing conditions.

The good news is that the work of the past three decades has laid a strong foundation for adaptation.

[Adaptive Reuse] We’ve learned how to take old, sometimes abandoned industrial and office buildings and turn them into appealing places to live, shop, study, and even work.

[Mixed Use] We’ve also learned that downtowns are stronger when there is a mix of uses… when they are 24/7 environments to “live, learn, work, play.” When you have a mix of uses, it makes it easier to add more of this and less of that.

So what’s next for downtowns? What is the next adaptation downtowns require? What do we have to do really well to accelerate the comeback of our downtowns?

Let me suggest three moves you can consider.

- Make the commute worth it.

Commuting is rarely enjoyable, and it’s become less so post-COVID. Driving to an office building, parking in the building, taking the elevator up, eating a quick lunch in the building or nearby, taking the elevator down and making the return drive home is not much of a pay-off for the hassle and expense of the commute.

With so many firms making “coming into the office” optional, those of you who manage downtowns need to assert yourselves.

What can you do to make the commute worth it? Can you make my life easier? Richer? More convenient? More fun? Less frantic? Less lonely? Healthier? Can you help me learn something new? Can you help me live my values?

All of that is possible in a good downtown.

- Double down on an alluring public realm

I hope you’ve had a chance to see at least one of the 5 new projects we’ve completed on our riverfront in the past 7 years. I’ve been a champion of great public places for a long time – at the Mayor’s Institute on City Design, CEOs for Cities, ArtPlace, Knight, Kresge, through our Civic Commons work, and now on the Memphis riverfront.

Our latest project is Tom Lee Park opened last Labor Day. Designed by Studio Gang and SCAPE, it has become an instant hit with locals, and to date, has generated positive press for Memphis in more than 70 national and international publications.

This month, we expect to welcome our 500,000th visitor.

The demographics of our visitors closely mirror the demographics of Memphis.

* 94% of visitors rank it good or excellent on cleanliness.

* 88% rank it as good or excellent on safety.

* 57% say they met someone new at the park.

That last statistic is deceptively important. Because if you can get people across the income spectrum to occupy the same space at the same time – not an easy task — and when occupying that space together, they expand their networks and meet someone new, there is the possibility of new economic opportunity for people with less income.

In fact, for a person whose household income is low, the expansion of one’s networks beyond one’s neighborhood is the most powerful way to break out of the tight hold “zip code is destiny” has on the fate of too many Americans living in high poverty/high distress communities. And we have many of those in Memphis and near downtown.

I believe public places, such as parks and libraries, alluring enough to attract people with enough money to be anywhere and also people for whom DisneyWorld is not an option, may be our last best hope for getting rich people and poor people to spend time together.

Now more than ever, we need great public spaces that draw people from across the city in the face of more income-segregation today across the U.S. than 50 years ago.

Don’t ever apologize for building great public space in your downtown.

To hear people say alluring places are not equitable, that they lead inevitably to “gentrification” is especially irritating when it comes to alluring places in downtowns.

Most downtowns are still transportation hubs. They aren’t the most accessible neighborhoods to each of us, but they are the most accessible neighborhoods to all of us.

Finally… in terms of what’s next for downtowns, I urge you to…

- Practice equity in public space

It’s not enough to build alluring public space, even if you do it with 43% MWBE participation, as we did in Tom Lee Park.

It’s not enough to lift up the mostly forgotten but powerful story of a Black man who acted with great courage when no one was looking to save 32 White lives from drowning in the Mississippi River, even though the hero, Tom Lee, could not swim.

It’s not enough to hire team members from nearby distressed neighborhoods.

Or to start building the next generation of riverfront champions by creating classroom curriculum mapped to the park and to host 14,000 school students in the park on field trips this semester.

Or to organize an apprentice program with certifications leading to good-paying jobs for high school graduates who are not immediately college-bound.

Those things are absolutely important. We’ve done them, and we are proud of our performance.

But the way we run the space is equally important.

If it is not clean and well-maintained, it disrespects the community.

If we don’t keep it family-friendly, parents won’t bring their kids.

If it doesn’t feel safe, people with options about where they spend time will stop coming.

If it doesn’t feel welcoming, people who wonder if something this good really is for me will stay away.

If it doesn’t feel generous, it is missing the “x factor.”

There is no formula… no recipe… no playbook that tells us how to “practice equity” in public space. In our case, we observe, we try things, we observe again, we tweak, we measure, and then we tweak again. Our method is continuous learning and continuous improvement.

But I want to tell you two quick stories of equity in practice. They are beginning to give us hints of how we might practice equity in public space everywhere.

The first is a very simple inspiration we had early on that didn’t seem like much at the time.

We wanted a park Welcome Center as part of the program. We didn’t know quite what the services would be, but we imagined it could do a laundry list of things – greet people coming into the park, offer information and directions, survey visitors. We were driven by the story of Tom Lee’s heroic rescue – the deep generosity and neighborliness of it. He was, indeed, his brother’s keeper.

This led us to adopt the “Hi Neighbor” message we use on ranger shirts and, eventually, on our park café, which has morphed into a ranger team who really understand our intention to get people to meet new people in the park. (Remember that 57% number?). It has created relationships between park regulars and rangers and led to equipment loans and dog treats. Bloomberg Center for Public Innovation has written about the impact of communicating a culture embodied in “Hi Neighbor” vs. police with guns patrolling a space.

Yes, sometimes, you need police. But the vibe that “everyone is welcome here” (as long as you act in a neighborly way) is a good beginning point to create a space where strangers can feel comfortable – even joyful — spending time together in public space.

The second is the product of an idea I had 4 years ago during a Sunset Kayak event on the harbor. We had a DJ on the water to set the vibe for kayaking, and between songs, he would encourage good behavior from participants… reminding people to return your kayak after 30 minutes, tell others about the event… really simple stuff.

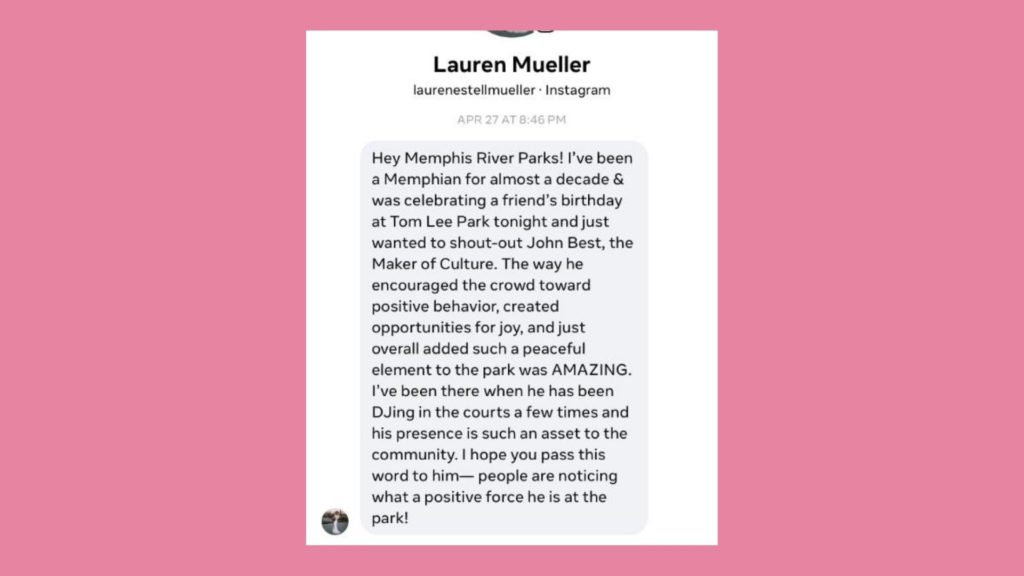

I thought then, John Best should be the official DJ in Tom Lee Park. I kicked the idea around for several years, while we continued using John for Skate Nights and various events. As a former professional basketball player who had traveled the world where he was always “the outsider,” he knew how to read a crowd with both his music and his messaging. He is a generous, confident, beautiful human being who knows how to use his talent for good.

Fast forward to last week when we announced John Best as our first “Maker of Culture” on the riverfront. Our rangers love having him in the park because, as they say, everything gets better, happier, more respectful when John is performing. He mixes messages into his sets, reminding people of park closing times, to dispose of trash, to keep it fun, to watch your children. But it never feels like he’s preaching.

And this is typical of the response we get…

Recently, I’ve been re-reading my friend Ryan Gravel’s book “Where We Want to Live” on the creation of the Atlanta Beltline. In it, he writes, “When infrastructure is done well, it compels others – hundreds, perhaps millions of people – to create a better life for themselves. It provides them with the incentive and the opportunity to build an apartment building, start a new business, host a picnic, perform a dance or tip their hat each morning when we see them at the market. While new infrastructures might also create beautiful landscapes or make convenient connections, their central purpose is to compel people to bring their city to life.”

Your job and my job is to bring our cities to life in a way that everyone feels included and everyone participates in public life – not because they have to but because they want to. This is about parks and public space and downtowns, yes. But more fundamentally, it is about luring us — across our many differences — into spending time together. It is about joy. It is about equity. It is about opportunity. It is about democracy.

Downtowns have a unique and outsize role to play in bringing cities to life. Thank you for being stewards of these important places.

Make the commute worth it? Maybe provide trains or bus rapid transit to the downtown so the commute isn’t necessary.