The following post is by Portland economist Joe Cortright. It previously was published on his City Observatory blog.

Must ReadThe problem with the “reckless driver” narrative. Strong Towns Chuck Marohn eloquently points out the deflection and denial inherent in the emerging “reckless driver” explanation for increasing car crashes and injuries. Blaming a few reckless drivers for the deep-seated systemic biases in our road system is really a convenient way to avoid asking hard questions about the carnage we accept as routine. Many drivers routinely engage in risky behaviors, from speeding to texting, to other distractions. What’s changed during the pandemic, is that their are more opportunities for these risks to turn catastrophic, because there’s less traffic. Ironically, traffic congestion holds down speeds and forces drivers to pay attention, diminishing possible crashes. The problem isn’t the recklessness, it’s all the driving.

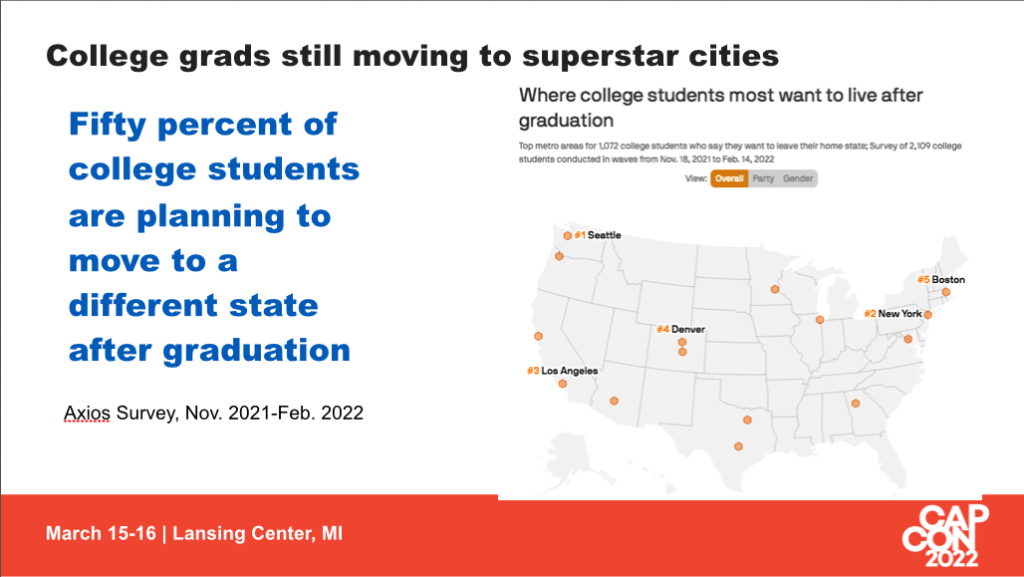

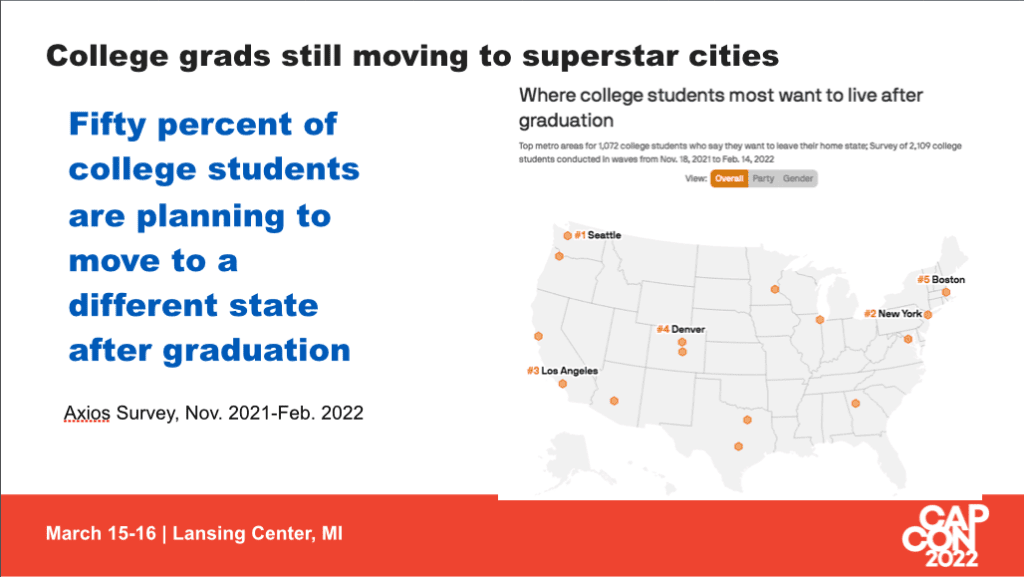

Where college students want to live after graduation. Axios has a new poll asking an important, post-pandemic (we hope) question: Where will young workers want to live. If remote work is as popular and prevalent as some think, young adults seemingly have more choice than ever about where to live and pursue their careers. The Axios survey shows that the new hotspots are . . . the same as the old hotspots: big vibrant cities, chiefly on the coasts. The great tech-hub exodus that didn’t actually happen. In theory, the advent of work-at-home ought to have undermined the need to be located in an expensive, superstar tech-hub. Finally, it was supposed to be the opportunity to flourish for second-tier cities that had been bypassed by the continuing concentration of firms and talent in a relative handful of established tech centers. But according to this article from WIRED, the theory isn’t panning out: for the most part, tech jobs remain concentrated in the long-established tech hubs. Drawing on data from the Brookings Institution, they report that:

A key factor underlying the persistent success of these tech centers is knowledge spillovers. WIRED quotes UC Berkeley’s Enrico Moretti, whose research points out the tech centers serve as force multipliers for idea creation and dissemination: scientists are more productive when they’re embedded in an environment with others, than when they are widely scattered. |