“They had a legitimate charge, but they had the wrong men. Everyone knows there was wrong done at the scene that night. If I did (know who killed Mr. Hayes, I would have told who did it.”

“They had a legitimate charge, but they had the wrong men. Everyone knows there was wrong done at the scene that night. If I did (know who killed Mr. Hayes, I would have told who did it.”

Part I: Introduction to a Teenager’s Murder.

Part II: The Incident

Part III: The Trial

Part IV: The Verdict

**

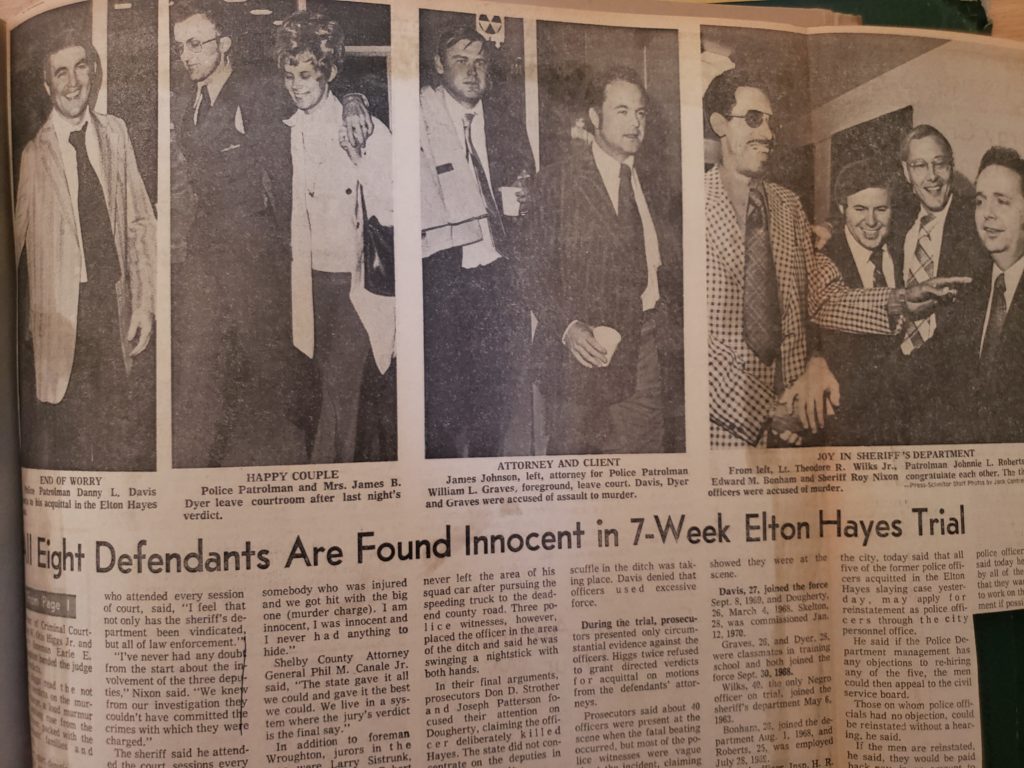

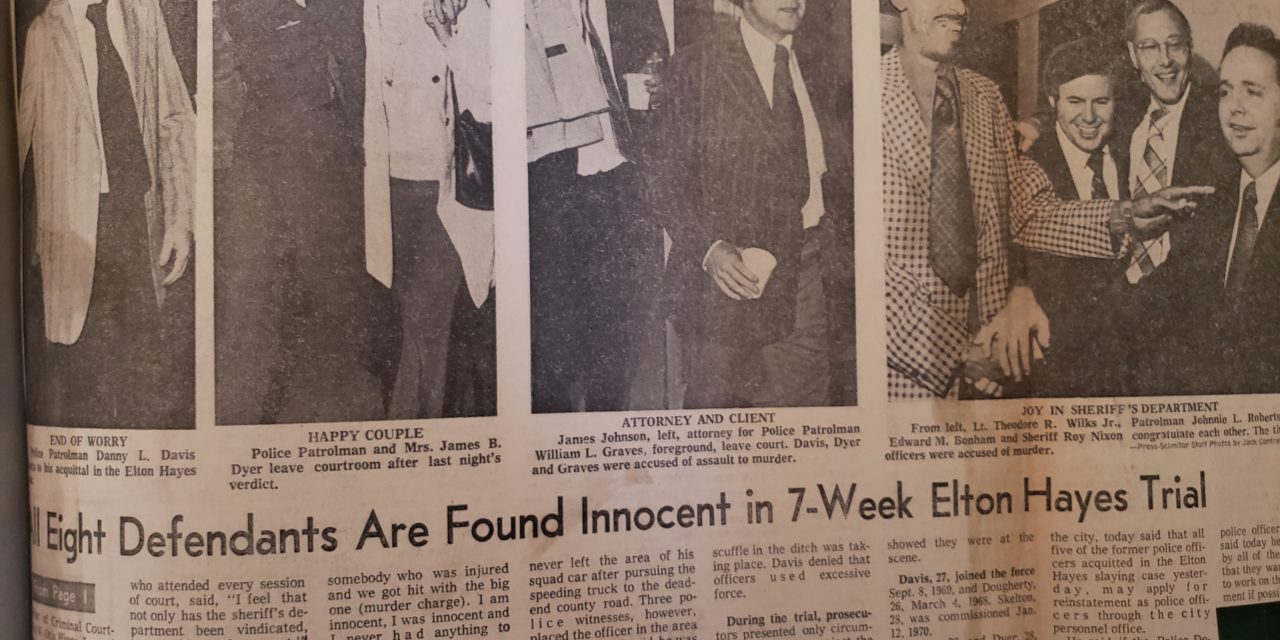

In the end, the verdict December 7, 1973, in the Elton Hayes murder trial felt familiar. The all-white jury of 12 men returned not guilty verdicts.

It mirrored verdicts commonplace in the South and reflected a long tradition, which continues today, of failing to hold law enforcement in Memphis accountable for mistreatment of African Americans. In the end, all eight law officers were acquitted in the murder of the 17-year-old Hayes and the beating of Calvin McKissack, his 14-year-old friend, after a high-speed chase on October 15, 1971.

Lt. Theodore R. Wilks Jr., charged with first degree murder in the death of Mr. Hayes and the only African American defendant, summed up what court watchers had concluded weeks before: “They had a legitimate charge, but they had the wrong men. Everyone knows there was wrong done at the scene that night. If I did (know who killed Mr. Hayes, I would have told who did it.”

By the time prosecutors made their final summations, it had become clear that Lt. Wilks was right. He and the other two sheriff’s deputies were ignored as prosecutors made their case for a murder conviction and instead focused on a Memphis Police patrolman.

By then, it had become equally clear that the trial strategy by prosecutors was cumbersome and muddied their narrative, and it seemed obvious from the evidence that the attorney general’s office had mangled the charges. Murder charges appeared to have been placed against the wrong defendants. Worst of all, they failed to evoke the terror of three teenagers facing 25-40 emotion-fueled law officers and how one of the youths didn’t make it out alive.

All in all, it fueled the belief in some quarters that the potential for justice in the case had been sabotaged from the beginning – when the indictments were returned by the Shelby County Grand Jury.

The trial featured a parade of police witnesses with only a couple providing any pertinent information, a missing tape of police radio conversations, a ruling by the judge that threw out confessions, and a defense attorney vilifying the teenage victims as criminals. All in all, as the trial unfolded, it fed predictions that justice would not be done.

Three sheriff’s deputies – Lt. Theodore R. Wilks and Patrolmen Edward M. Bonham and Johnnie L. Roberts – and one city policeman – Michael J. Dougherty – were indicted on first degree murder charges. Four city policemen – Danny L. Davis, Larry R. Skelton, James B. Dyer, and William L. Graves – were charged with assault to murder in the beating of Mr. McKissack, Mr. Hayes’ 14-year-old companion in the truck. Police Inspector H. R. Ray was indicted on a charge of neglect of duty, a misdemeanor, and his case was severed for a separate trial. All of the defendants were White except for Lt. Wilks. None of the indictments addressed an attack on George Barnes, 15-year-old driver of the truck.

Following the verdicts, Shelby County Sheriff Roy Nixon, who attended the trial each day, immediately hired back the three deputies charged in the case and held a victory party in his office. If that was not enough, he promoted all three. Deputies Roberts and Bonham were promoted to the rank of sergeant and assigned to the Detective Division. Mr. Wilks was promoted to captain, becoming second in command of the sheriff department fugitive squad.

Meanwhile, at Memphis Police Department, Chief Bill Price said, “I feel sure they (the police officers) will” be reinstated if they apply.

The responses were unseemly since they seemingly forgot there remained the inconvenient fact about a dead teenager in a ditch in Capleville after a five-mile chase. There was also the undeniable fact that he had been killed by police, who attempted a cover-up by initially blaming his death on a traffic accident.

As the not guilty verdicts on the murder charges were being read by Criminal Court Judge W. Otis Higgs Jr., a loud murmur and sobbing rose from the courtroom which was packed by defendants’ families and friends. After the judge read acquittals on the assault to murder charge, spectators cheered and Defendant Davis jumped to his feel and hugged other defendants as the bailiffs tried to restore order.

Speaking for the deputies charged in the case, Lt. Wilks said: “My men and myself had done no wrong in our stumble bumble way to help somebody who was injured and we got hit with the big one (murder charges). I am innocent, I was innocent and I never had anything to hide.”

Primary evidence against the deputies was blood on their uniforms. The deputies said they only touched the teenage victim when they carried him to a squad car to be taken to John Gaston Hospital. They said policemen were swinging nightsticks in the ditch where they found Mr. Hayes with blood flowing from his head.

Police contended that the truck occupied by the teenagers had attempted to ram a squad car and when that was radioed to the dispatcher, dozens of cars took up the chase with as many as 40 law officers arriving at the scene after the truck slid into a ditch. Police apparently focused their anger on Mr. Hayes on the mistaken impression that he was the driver of the truck rather than Mr. Barnes. The medical examiner’s office testified that Mr. Hayes died from nine blows to his head. Six were strong enough to cause brain damage and four cracked his skull.

In their final arguments, prosecutors did not concentrate on the sheriff’s deputies, and instead focused on Patrolman Dougherty who they said intentionally killed Mr. Hayes.

Prosecutors said about 40 officers were present at the scene when the fatal beating took place, but most of the police witnesses at the trial were vague, claiming the lighting was too poor to see the activities of the defendants. This was despite residents in the area testifying that it was well-lighted.

Prosecutors came under withering criticism for their handling of the case, and six weeks after the not guilty verdict, Attorney General Phil M. Canale Jr. resigned. Four days later, another Criminal Court jury returned a not guilty verdict against a policeman accused of striking a prison in the city jail.

In its way, the Elton Hayes case falls into the category of what’s past is prologue, because over the ensuing years, we can count on the fingers on one hand cases where police officers or sheriff’s deputies were charged for abuse of African American Memphians and Shelby Countians.

The attorney general’s office earlier this year established a new prosecution unit targeting police brutality cases and has filed cases against two law enforcement officers. That said, it’s too early to tell if the new Conduct Review Team will deter excessive force. After all, the local attorney general’s office has a poor record in that regard.

Memphis Police leaders say they support the team, and it remains to be seen if this is just a different process producing the same results. Regardless, it’s telling that such a unit was not created until 50 years after Elton Hayes murder.

Still remember this. I was nine years old at the time. Just goes to show that not much has changed in 50+ years.