Thumbnail: The national attention to the crack on the I-40 bridge in downtown Memphis gives advocates of a third bridge an unforeseen opportunity to make their case to federal officials and local citizens.

**

Stanford University economist Paul Romer famously said a crisis is a terrible thing to waste.

The pithy epigram is especially true for our community as a result of the crack in the Hernando de Soto Bridge.

But the crisis is not ours alone. In truth, it is national crisis, because the break in the bridge is in truth a break in the national economy.

As every economist knows, I-40 is a crucial current for the economic life of the U.S. and the interstate highway’s bridge crossing the Mississippi River is a vital link that makes it possible.

When Andrew Carnegie built the first bridge across the Mississippi River in 1874 – at St. Louis, he said he was uniting America with the “eighth wonder of the world.” And yet, the wonder was not just in its use of a steel structure but the economic wonder from removing a formidable barrier that disconnected the economy of east and west United States.

Infrastructure Backing

Today, there are about 130 bridges across the 2,320 miles of the Mississippi River, but only a handful – arguably only four or five – have the importance of the 50-year-old I-40 bridge. Short of a New Madrid Fault earthquake, there are few events with an economic impact as negative as the loss of this major bridge.

For those advocating a third bridge in the Memphis area, to make sure this crisis is not wasted, it’s an opportunity to do more than fix the bridge.

The idea for a new Mississippi River bridge dates back decades and transportation studies have been undertaken for more than 15 years. So far, it’s not gained the kind of traction it needs to justify an investment that could be as much as $1.5 billion.

For context, consider that the Hernando de Soto Bridge cost $57 million in 1967, which is $476 million in today’s dollars.

Infrastructure investments are a priority of the administration of President Joe Biden to create more blue collar jobs, increase middle class incomes, and improve national competitiveness. In the best of times, any investment of this size requires considerable political capital, and in an age of naked and unyielding partisanship, this is a considerable challenge.

A Third Bridge?

It’s yet to be proven that the Republican governors of Arkansas and Tennessee and the states’ Republican majorities in Congress can support the Biden infrastructure initiative that might provide funding for a third bridge. A unified coalition of Tennessee state and Congressional politicians would be absolutely essential to cut through the blizzard of funding requests for federal transportation money.

The politics of a new bridge may be further complicated because of the potential need to involve Mississippi officials and the likelihood that “Memphis third bridge” might not be in Memphis at all. Studies about alternative locations of the bridge shows one of the strongest routes to be south of Memphis below the Mississippi state line. It is a given that if the proposal for a new bridge gained momentum, that state’s government and political officials will press a location in their state.

An equally important issue is the money itself. Tennessee Senator Bill Hagerty has pending legislation proposing $311 billion for bridge repair and construction projects over five years. That’s an average of $62 million a year and with one out of three interstate highway bridges needing repairs, that’s hardly enough to make much of a dent in the need.

In the same bill, there is only $3.3 billion in the bill for new bridges, and it is said that a third bridge in Memphis could cost half that amount. The reality is that there are other cities lobbying for federal money for new bridges, so the case for a third bridge here would have to be especially persuasive.

That will undoubtedly surface this week when U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg visits Memphis on Thursday. While his purpose in Memphis is for an update on the repairs for the I-40 bridge, it is a certainty that a third bridge will be mentioned in the discussions.

Funding A Bridge With Tolls

The 2011 study for a new bridge – the so-called Southern Gateway – summarized its needs this way:

Need #1 – The need to improve infrastructure to withstand a major earthquake.

Need #2 – The need to improve the movement of freight on roadways and railroads.

Need #3 – The need to increase capacity and improve operations for vehicular traffic.

A 2009 feasibility study evaluated the possibility of a toll bridge (the former head of Memphis MPO argued that tolls couldn’t be levied on an interstate highway when several of us called for them on I-269); however, the report assessed five potential routes and projected net revenues from the tolls (in 2018 dollars) in the first year from $11.7 million to $22.4 million, growing to $81 million to $249.3 million in 40 years.

The costs for the alternative routes for a new bridge were estimated from $451 million to $709 million and construction would take five years.

The report estimated that 20 years after the bridge is built it will have produced $2.2 billion increase in Gross Regional Product, $1.5 billion increase in personal income, and an increase of 32,500 jobs. Today, the gross regional product is $78.9 million and there were 657,000 jobs pre-pandemic.

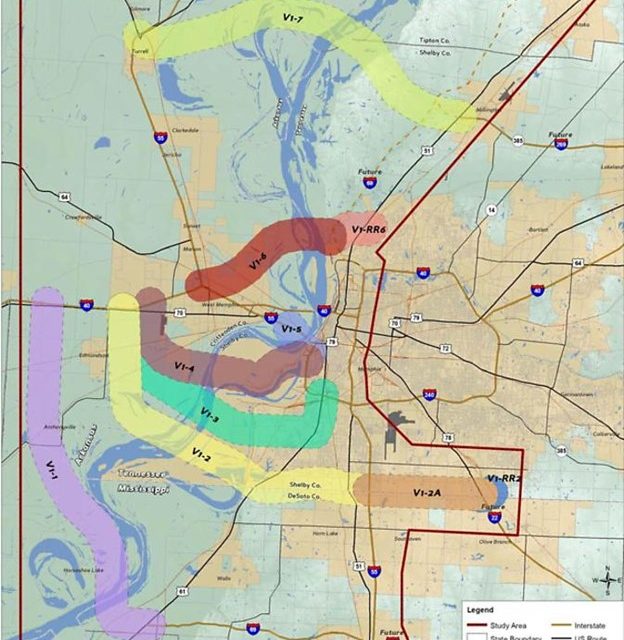

Alternative Locations For A Third Bridge

The five alternative locations for a new bridge listed in the 2009 report are:

* Alternative 1 – This is the most southern alternative with its eastern terminus located on Interstate 55 approximately five miles south of the Tennessee-Mississippi state line. The western terminus is located on Interstate 55 approximately four miles west of the interchange between Interstate 55 and Interstate 40 in West Memphis. Intermediate full access interchanges are assumed with Mounds Rd, US 61, and Goodman Road. As studied, Alternative 1 is approximately 23.5 miles in length.

* Alternative 2 – The western terminus of Alternative 2 is the same as Alternative 1. The eastern terminus is located near interchange 8 of Interstate 55 southwest of downtown Memphis. Alternative 2 is approximately 13.5 miles in length and includes an intermediate full access interchange with Mounds Rd. This alternative would run through a really tight corridor between a large rail yard and the Valero oil refinery.

* Alternative 3 – This location is between North Memphis and Frayser in the general area where I-40 turns south. The western terminus is located at the interchange between Interstate 55 and Interstate 40 in West Memphis. The alternative proceeds northeast before turning east and terminating at the interchange between Interstate 40 and State Route 300 in Memphis. Alternative 3 has a full access interchange assumed with Mound City Road and is approximately 10 miles in length. Alternative 3 and 4 run between General DeWitt Spain Airport and Maynard C. Stiles Wastewater Treatment Plant.

* Alternative 4 – Alternative 4 is quite similar to Alternative 3. The only major difference between Alternatives 4 and 3 is that the eastern terminus of Alternative 4 is located at the interchange between SR 300 and US 51, approximately one mile northwest of the Alternative 3 eastern terminus. Similar to Alternative 3, Alternative 4 is approximately 9.5 miles in length and includes a full access interchange at Mound City Road.

* Alternative 5 – The most northern of the five alternatives studied and north of Frayser . The western terminus is located along Interstate 55 approximately five miles northwest of its interchange with Interstate 40. The eastern terminus of Alternative 5 is located along US 51 near Firestone Park. Alternative 5 has no assumed intermediate interchanges and is approximately 10.5 miles in length. Alternative 5 was analyzed based on connectivity to a future Interstate 69.

A Pitch To Buttigieg

The 2011 study dubs the bridge “The Southern Gateway project,” and said it “originates from several previous studies and investigations related to improving the regional transportation system. Early studies such as the Memphis to Pine Bluff Freeway Study conducted in the early 1990s and more recent studies, such as the Mississippi River Crossing Feasibility the Location Study completed in June 2006 and the Mississippi River Bridge Toll Feasibility Study completed in early 2009, all have a common theme: eventually another highway bridge across the Mississippi River will be needed in the Memphis area.”

One thing is certain: the need and the cost will only grow over time. Looking back, the cost estimates from 2009 seem like a bargain, and every year a new bridge is not constructed, today’s cost projection only go in one direction: up.

That’s a point bridge supporters hope to make during Secretary Buttigieg’s visit while emphasizing the potential of an inter-state political coalition.

That said, there will unquestionably be internal political considerations that will require attention.

Politics – Inside And Out

Downtown supporters, influential downtown business leaders, and tourism officials are likely to question the impact of a new bridge distanced from the CBD.

The likelihood of one in Mississippi will attract intensive opposition although the average daily traffic counts on the I-55 bridge indicate that the pressure is on the southern crossing. It has seen increases over the past decade while the counts on I-40 have gone down, which will lead some to question the need for the bridge at all.

There will also be opposition based on the perception that a new bridge is justified primarily to help move freight more quickly through our region. Already, there are concerns that the region’s overreliance on TDL jobs contributes to an economy failing to keep pace with our peer regions.

Because of the crack in the I-40 bridge, our regional economy is in crisis. If it is not repaired quickly, we run the risk of long-term economic damage as companies consider whether they should relocate to a region with fewer risks for a similar crisis.

With national attention on I-40 bridge’s crack, this is likely the best opportunity advocates will have to make their case for a third bridge but it will require equal attention to garnering tri-state political support and convincing Memphians it is in their best interest.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis and the conversations that begin here.