The power of partnerships has become a threadbare talking point from political overuse but that makes it no less true. The evidence is seen in the rebooting of the cobblestone preservation project on the riverfront.

City of Memphis, in partnership with the Memphis River Parks Partnership, has jumpstarted the project that seemed at times like it would never get done, even with the state funding, long held in abeyance, to make it happen.

The project to restore these civic monuments was delayed seven years ago when State of Tennessee engineers expressed concerns about the safety of the railroad crossings on the riverfront, but a couple of weeks ago, City of Memphis filed a $6.3 million building permit for the project.

That was made possible by city engineering’s new designs for the crossings and synchronized signals that have been submitted for state approval. Armed with that approval, City of Memphis could begin the bidding process to select a contractor next month, and with the attention given to it by the Strickland Administration, the public could see work on the cobblestones as early as the fall.

Well-Traveled

The sequencing of the work will be driven by river levels, but would include removing inappropriate materials like concrete and asphalt, moving the utilities underground, stabilizing the bank, adding ADA access, and building foundations for two river overlooks.

The restoration and preservation of the cobblestones, which celebrate its 40th anniversary on the National Register of Historic Places this year, is a significant piece of the plan under way that is restitching together a riverfront that has been isolated and had disconnected nodes of activity for decades.

The historic profile of the cobblestones was raised in May of last year when several hundred of them were taken from storage and shipped to Venice, Italy, for its internationally prestigious Architecture Biennale. The purpose, according to Jeanne Gang of Studio Gang, was to explore the question: “How do you make the stones talk?”

Metropolis magazine reported:

“From Gang’s stone foundation, the U.S. Pavilion (commissioned by the University of Chicago and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago offers myriad takes on similar questions of civic histories. With the theme ‘Dimensions of Citizenship,’ the seven participating teams of artists, architects, and researchers work at a wide range of scales, from the personal to the global. Inspired by the Eameses’ Powers of Ten, the pavilion’s curators—SAIC assistant professor of architecture Ann Lui, Niall Atkinson of the University of Chicago, and writer and curator Mimi Zeiger, with associate curator and SAIC lecturer Iker Gil—present two queries: ‘What does it mean to be a citizen today?’ asks Lui, and ‘What is the role of architecture in researching, intervening in, and speculating on these questions of belonging?’

“Five hundred stones previously held in storage (of about 800,000 at the landing) were transported to Venice, where they were installed inside William Adams Delano and Chester Holmes Aldrich’s neoclassical pavilion in the Giardini della Biennale. It’s one of the first exhibits visitors see as they enter the pavilion—a strong tactile and physical presence, where the stones gradually slope up into a chamfered corner. Gang’s landing is made of nine types of stone that the Memphis landing comprises, arranged to accentuate different colors and textures: brilliant pink granite, intriguingly speckled gneiss, and plain-Jane gray limestone. Off to the side of the entrance, nine augmented cobblestones—diced, spliced, and then pieced back together—thematize stories told by exemplary Memphians in an accompanying film produced by the filmographers Spirit of Space. There is similar scalar diversity at work in the film, from a segment about the mayor’s citywide agenda to a clip devoted to local artists working with youth.”

Laying Down History

Memphis was only 40 years old when the $83,333 contract – the equivalent of $2.4 million today – for laying the cobblestones at the Great Memphis Landing was approved in 1859 and awarded to John Loudon of Cincinnati. The contract called for “paving the wharf with limestone or granite, of not less than four nor more than eight inches in surface, to be laid on gravel not less than five nor more than eight inches in depth; the width of the pavement to be 100 feet, the length 3300.”

It called for “paving the wharf with limestone or granite,” and it was likely the largest public works project by the City of Memphis during the antebellum era. The limestone cobblestones were quarried on the Ohio River in Hardin County, Illinois, near the tiny port town of Cave-in-Rock and floated down by ship and barge to Memphis to create what today is the largest remaining intact cobblestone landing in the U.S. The work continued contemporaneously with the Civil War and wasn’t completely finished until 1881.

If you are a glutton for this kind of historical background like us, read on with the following, which comes from the Cultural Resources Assessment of Memphis landings in 1995:

The present Memphis Landing is the surviving portion of a series of four river landings developed along Memphis’ frontages with the Mississippi and Wolf rivers between 1819 and ca. 1881. Today’s Landing includes portions of the South Memphis Landing, developed between Union Avenue and Beale Street beginning in 1838, and the southern portion of the great Memphis Landing, first developed in the 18405 between Jefferson and Union avenues.

Before 1859, the appearance of the great Memphis Landing and the South Memphis Landing were quite different from the existing vast but well-defined stone pavement. Printed images from the 1840s and 1850s show the Landing as an expanse of rough, exposed, eroded bluff terraces, divided by east-west road cuts through the terraces to reach a narrow strip of land at the water’s edge. The river’s edge, a much smoother plane of clay and silt, was subject to erosion by the currents of the Mississippi River and proved to be an unreliable place for river traffic to land. Falling water levels often revealed impassable sheer drops in the slope of the embankment, caused by erosion of the bank by river currents during high water levels. The vertical movement of the Mississippi River is astonishing, sometimes exceeding 50 feet between periods of high and low water and 30 feet between average annual high and low water. During periods of low water, river passengers and laborers were forced to traverse two hundred to three hundred feet of the unstable bank before reaching compacted ground. Newspaper descriptions from this period suggest that crossing this embankment of mud was usually difficult, and virtually impossible during rainy periods.

Historic Landing

The City of Memphis recognized that the surface of the Landing should be improved. Center Landing, between Adams and Poplar avenues, was paved before 1859. However, paving the portion of the Landing that remains today was not considered until 1859, when the opening of the Memphis & Charleston Railroad fueled a boom in activity at the Landing to connect river with rail transport. At that time, the City hired paving contractor John Loudon to initiate ‘paving the wharf with limestone or granite” between Adams and Union avenues to cover a width of 100 feet and length of 3,300 feet. Amendments to Loudon’s contract set the thickness of the paving at 12 inches and extended its length to Beale Street. The stone used in the project was quarried in Illinois; contrary to popular and longstanding myth, it did not originate as ballast stones in sailing ships.

Loudon began the work in 1859; by August 1860 the City Engineer reported that Loudon had completed 19,558.27 square yards of paved surface. The project was halted soon after the outbreak of the Civil War. Loudon resumed the project in July 1866. Subsequent contracts with Loudon’s sons and other contractors brought the Landing to completion in 1881. Analysis of the remaining pavement fabric on the Landing strongly suggests that at least portions of each of these paving projects remains in place today.

By the early 1880s, the original Memphis Landing at the mouth of Bayou Gayoso near Auction Avenue had been rendered obsolete by accretions of the river bank to the west. Center Landing was in the process of eroding away and was landlocked by the late 1880s. The focal point of commerce on the Memphis waterfront permanently shifted to the great Memphis Landing and the South Memphis Landing, then recognized as a single place.

The paving of the Memphis Landing between 1859 and 1881 was arguably the largest and most complex public works project undertaken by the City of Memphis in the nineteenth century, perhaps rivaled only by the construction of George Waring’s revolutionary sanitary sewer system, which began in 1879. The completion of the Mississippi and Tennessee Railroad line across the brow of the Landing in 1882 established a direct connection between the river and rail terminal.

The Collective Importance

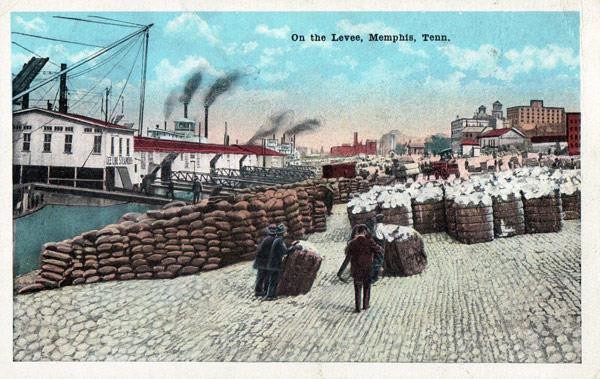

For the next fifty years, the Landing bustled with activity. The growth of the nation’s railroads slowly diminished the importance of the Landing for passenger traffic, especially after the completion of the Frisco Railroad Bridge in 1892. Still, the river remained a necessary connection between the rich cotton plantations of the Mississippi and Arkansas deltas and the industrialized North. The poor quality of the road systems in the Mid-South region guaranteed that the river would remain an important transportation route for agricultural crops well into the twentieth century. Local steamship lines like the Lee Line and national carriers like the Anchor Line originated service from the Memphis Landing and continued to make Memphis a port of call on their routes, with daily trips until the 1930s. Individual steamships such as the Lee Line’s Kate Adams attained such status in the city’s collective consciousness that their names are still familiar to most Memphians.

It is difficult to pinpoint when the Memphis Landing began to slip in commercial importance and prestige. Some argue that the completion of the Frisco Bridge started the decline of the Landing’s commercial role; others point to the region’s escalating agricultural depression that began in the 1910s. An important factor was the isolation of the Landing from the main channel of the Mississippi River by the growth of Mud Island beginning in the 1910s. In all likelihood, a combination of these and other factors changed the role of the Landing in city life.

Harland Bartholomew proposed altering the Landing for a new purpose in the city’s first comprehensive city plan, completed in 1924. Since then, urban planners, architects, and city leaders have occasionally proposed a solution to the question, “What shall we do with the Memphis Landing?” To date, the complex terrain of the river bluffs and the Landing itself have combined with the formidable and fickle Mississippi River to render many proposals impractical or impossible. Riverside Drive was constructed across the brow of the Landing in the 1930s; apart from that road project, the other proposals, including the massive parking lots proposed by Bartholomew, the 17-lane interstate highway, the heliport, and the megalithic apartment building included in other plans have all been considered briefly but discarded.

One probable reason for the survival of the Memphis Landing into the 1990s is its special place in the collective memory of Memphians. At its peak, the Memphis Landing played a role as important to the commercial and civic life of the city as the FedEx “Hub” and Memphis International Airport are in our own times. Perhaps its preservation has been accomplished in recognition of its valued service to the Memphis community, not just for its place in the City’s economic development over a century and a quarter, but also in memory of the thousands of unknown people who built it and moved the commerce of the city across its surface.

For a much larger group, those who might be in Memphis for only a few days or even a few hours, the Memphis Landing provides a rare opportunity to approach the edge of the waters of the Mississippi, to touch the water if they wish to. Though this may seem insignificant to Memphis residents, the powerful place held by the Mississippi River in our national heritage, our literature, and our music is a magnet for visitors who feel attracted to this mighty waterway. Along its entire route, there are few places where the topography allows one actually to reach the river easily. Keeping the Memphis Landing as one of a very few urban places to experience the Mississippi River may be enough to justify its preservation.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis and the conversations that begin here.

I was just walking on them a couple of weeks ago.

I really hope, that this cobblestone landing gets improved, so that people can enjoy it and learn from history.