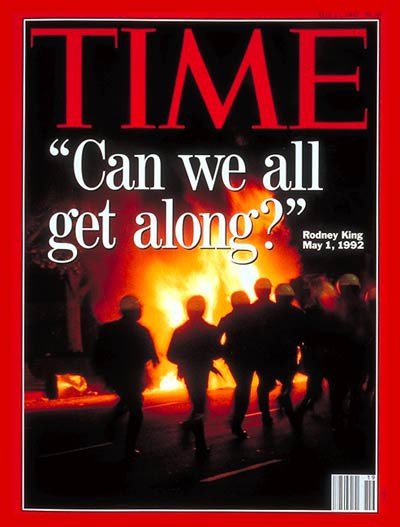

Twenty-five years ago this week, Los Angeles’ simmering police racism erupted into the open when the police officers who had viciously beaten Rodney King were acquitted.

It led to what was called by officialdom as the “LA Riots,” but was known more often as the Los Angeles civil unrest or civil uprising by those working at the grassroots in that city.

But long before Rodney King, there was Marquette Frye, and their lives were linked by 1965.

Mr. King was born April 2. A little more than four months later, on August 11, Mr. Frye, a 21-year-old African American, was stopped for reckless driving by a California Highway Patrol motorcycle officer.

Frye’s mother was called to the scene, an argument took place, rumors spread, a crowd formed, and that spark touched off the anger over law enforcement racism, which in turn resulted in the Watts Riot, sometimes called the Watts Rebellion, six days of looting and arson marked by 34 deaths and about 3,400 arrests within a 46-square mile area of the City of Angels. It would be the largest riot in Los Angeles until the Watts Riots following Mr. King’s acquittal.

Two Links On The Same Chain

It’s tempting to see the two events as independent milestones in Los Angeles’ racial history, but in truth, they were a continuum, not just in the history of L.A. racism, but as mile markers in the nation’s relentless march toward African American mass incarceration.

It is likely that news analysis this week will concentrate on the 1992 “L.A. Riots” as a single event rather than as the progression of events that ironically began in the midst of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society programs to eliminate poverty and racial injustice.

Looking back, there are no heroes in this story, and there is plenty of culpability to go around – both political parties and politicians of all political philosophies.

It is arguably the most devastating public policy stories in American governmental history: after ignoring warning signs of coming racial strife, a city explodes, prompting a burst of national self-examination and policies, and yet, all the while establishing a framework in which decisions about the future would be made that put more African Americans in contact with the criminal justice system.

This framework was anchored in assumptions that treated families in poverty as problems, saw adolescent behaviors through a delinquency lens, presumed inner city neighborhoods were powder kegs, and considered African American families as in crisis. The connection between this framework and the attitude of some police officer toward African Americans remains to be researched, but the implied effect seems clear to us.

Blaming The Victim

If any single report documents the tenor of that time, it was the Moynihan Report, written by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a sociologist working as Assistant Secretary of Labor for President Johnson. It too is connected to 1965 with a title distinctly of its time: The Negro Family: The Case for National Action.

His treatise on racial inequality was influential, although the Johnson Administration backed away from it when it provoked a liberal and African American uproar. Mr. Moynihan’s premise was that destructive ghetto culture and dysfunctional family structures were responsible for a rise in families headed by single women which in turn had produced a matriarchal culture that undercut the role of black men.

While researchers still argue about the causes of poverty and inequality, there is no debate today that the problems of people in poverty go far beyond the structure of families. That was always our problem with the Moynihan Report: it was concentrating on the symptoms rather than the causes.

However, the report still had impact in federal policies because it shaped the narrative about African American families and neighborhoods. As a result, while federal programs produced headlines about racial progress, the emerging social policies were setting in motion forces still causing structural challenges today.

Seeing Inner City Neighborhoods As The Problem

While the Great Society War on Poverty programs were being established, so too was the foundation for a criminal justice system that would put in prison a staggering number of young African American men in urban areas like ours (which today has one of the highest incarceration rates in the U.S.).

We cannot think of a president since Mr. Johnson who has not proposed laws and programs to step up policing in America’s major cities, to expand the prison-industrial complex, and to join the War on Drugs, all while disproportionately targeting African Americans.

In particular, a central theme for these criminal justice programs was the notion of unemployed African American youth as dynamite just waiting to be lit. By 1977, the federal government had spent $6 billion ($25 billion in today’s money) in 12 years for new law enforcement programs, including the Safe Streets Act, whose title alone suggests how the federal government defined the need for urban streets.

As Elizabeth Hinton wrote in her book, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America, the federal government even created grant programs funding for community development organizations willing to link up with the criminal justice system. For example, she points to a U.S. Department of Justice program that provided funding for grassroots organizations that agreed to label youth as “pre-delinquent” and to share space with law enforcement agencies so they could watch them.

Locking Up Better Ideas

In this way, these programs were self-fulfilling prophecies and in time, punitive approaches were welded into every corner of the social welfare system. The Law Enforcement Assistance Agency plowed millions of dollars in street patrols, most often in large cities with significant African American communities, and in addition, grant programs paid for new and bigger jails and prisons whose inmates were largely people of color.

That said, as we have proven in Memphis, the reliance on incarceration as a primary crime control policy has only a small impact on public safety and a significant impact on government budgets. For example, from 2001, the cost of the Shelby County Jail has tripled (now approaching $100 million a year and in the past 10 years, it has grown at a rate three times education).

At the same time, the number of youth and mentally ill people in the jail has grown, and jail overcrowding is once again a problem because of the law of unintended consequences: elected leaders lobbied again for longer mandatory sentences, and as a result, more defendants go to trial, remaining in the jail until their day in court.

The Shelby County Sheriff’s Department received a $150,000 grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation to develop programs aimed at reducing jail population by “changing the way American thinks about and uses jails.” The department made little progress on doing something innovative or it would have likely received more funding, like one of the grants for $1.5 million to $3.5 million awarded to 11 jurisdictions.

Tougher enforcement, more arrests, and longer sentences remain our go-to responses to spikes in crime rates. It’s hard to get politicians to take the long view about the cyclical nature of crime when constituents are breathing down their necks for instant answers, but more and more enforcement and incarceration largely reflects the federal priorities set from the Johnson Administration forward.

Thinking Long Term In A Short Term World

In the last couple of years, a group of criminologists has refined how policing gets evaluated, generating new perspectives and even contradicting conventional wisdom. In particular, they cautioned against responding to outliers like a large spike in murders by looking for quick fixes.

Using new analytical tools, there were two threads that ran through most of the group’s recommendations:

* Pinpointed targeting of the most dangerous people and places

* Solve underlying social problems instead of just treating symptoms of those problems with brute force

Fighting The System

And that takes us back to where we began. Fifty-two years after the Great Society, we still are trying to solve causes. We often talk a good game, but in the end, we come up short because we are not courageous enough in our strategies and we do not sustain them when we hit the first bumps in the road.

But more than anything, we do not solve them because the system has been constructed in such a way that African Americans remain disproportionately represented in criminal justice, both in arrests and incarceration.

We tend to address them with a sense of immediacy that treats them as problems of the moment. As a result, we don’t approach them with the long view in mind, and we certainly don’t address them with the systems change that can deliver more than incremental progress.

Today, concentrated poverty exists in twice as many census tracts as in 1970, inner city neighborhoods’ densities are roughly half of what they were then, and more than five times more African American men are in prison than whites.

Once more, it proves that every system – especially one carefully constructed over 50 years – is perfectly designed to produce the results it gets.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.