It’s City Hall’s Greek chorus: We’ve got no money and financial times have never been tougher.

And yet, in the midst of the mantra, there are approvals for millions of dollars in city funds for profit-making projects and millions more being waived in tax freezes for private companies.

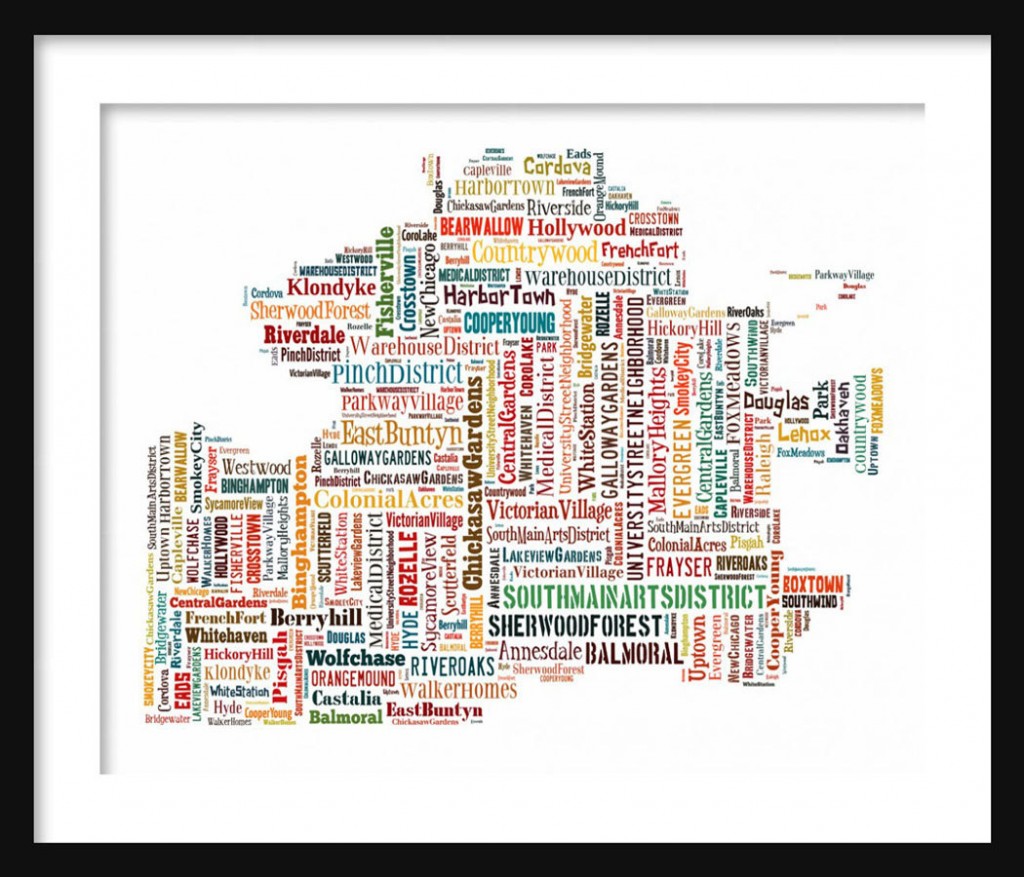

Watching it all from Memphis core neighborhoods that have seen meager investments in the past 15 years, their question seems obvious: Do we ever get to the front of the line when they’re giving out money?

While few things in Memphis and Shelby County get more lip service than neighborhoods (well, maybe, children), requests for money for neighborhoods regularly meet with explanations about how important neighborhoods are but how there just isn’t any money for them in such tight budgetary times.

All The Above

And yet, Memphis City Council approves funding for developers like the recent project at Union at McLean for residential development and possibly a grocery store. City Council’s $4 million loan/grant for that project is to be spent for demolition and public infrastructure (although Kroger’s expansion just up Union received no similar consideration.) The project also received a $15 million tax freeze, meaning that it gets a pass on $10.5 million in city and county taxes.

It represents a trend that has developed in high-profile projects. Rather than select which one of the business incentives they want – a tax freeze or city funding – developers select all of the above.

For example, Crosstown Concourse got a 20-year freeze waiving about $42 million in city and county taxes. To top it off, the developers also asked for money from local government, getting $15.2 million from City of Memphis and $5 million from Shelby County.

Another was the Chisca Hotel redevelopment, which got $2 million from City of Memphis to go with a 20-year tax freeze worth about $6 million, and Tennessee Brewery got a 20-year tax freeze worth more than $7 million plus $5.1 million from the Downtown Parking Authority for a parking garage plus $2.5 million from city government.

There are other high-profile private projects that have also gotten direct funding from city government, benefitting both from their merit and the political influence of their backers, but they also benefit from economic impact reports that are of course self-serving and incomplete. For example, with the Union at McLean project, the report said that a new grocery store would increase sales taxes – although it’s more likely that spending at that location is simply moved from other locations so there’s no significant net gain.

It’s Neighborhoods’ Time

We’re not saying that these projects aren’t important. In fact, the ones downtown are nothing short of transformational.

But here’s what we are saying: If City of Memphis can find money, give away taxes, and issue capital improvement bonds to help projects like these, it can do it for neighborhoods as well.

What neighborhoods obviously lack are the political clout and the unified front that refuses to be ignored. But they also need local governments that demonstrate that they value their opinions and back it up with processes to give them opportunities to have a voice in public funding decisions. It is in creating a constituency for neighborhoods that they have their best chances to develop the political backing for the investments that they want and need.

In fact, at the same Memphis City Council meeting where they heard the presentation about plans to renovate the old Sears Crosstown megalith into an activated hub to stimulate the Memphis economy, Council members were presented with plans for the Klondike/Smokey City neighborhood north of the project.

No Local Funding For Community Development

One slide said it all: 1) Neighborhoods are the building blocks of community, 2) Memphis is a city of neighborhoods, and 3) Redevelop Memphis inside out, neighborhood by neighborhood. The good news is that the Crosstown Concourse proponents pledged an unspecified amount of money to support the Klondike/Smokey City plan, which includes realistic housing and commercial demands as well as improvements to the public realm.

And there’s the rub. Although the Council approved $15 million for Crosstown Concourse, it approved nothing for the neighborhoods plan.

But it was hardly surprising. There are about 4-6 neighborhood plans sitting on shelves in city government waiting for the funding to implement them.

Unlike many comparable cities, Memphis puts no money into the budget for community development. It hasn’t for at least a decade. Instead, whatever is done in Memphis hinges on how much federal money comes to Memphis Housing Authority and Memphis Division of Housing and Community Development.

It seems a good time for City of Memphis – and Shelby County Government, for that matter – to approve funding to support and strengthen Memphis neighborhoods. After all, if the neighborhoods grow stronger, they produce more property tax revenues to fund the services of local government.

Choices Are Being Made

While it would have been good to have done it earlier, it’s more and more mandatory now with yearly declines in federal funding from HUD. That was a reason that the funding for the development at Union and McLean was so controversial. The money came from federal funds that could have also been spent on neighborhoods.

That decision may or may not have been the right one, but our concern is that these decisions are often not treated as the choices that they are. Instead, they are political transactions rather than policy decisions, and as we’ve learned over the years, it’s the politics that comes out the victor.

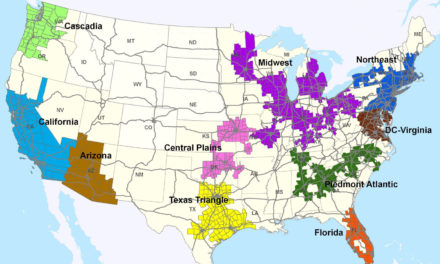

For more than a decade, the Shelby County Board of Commissioners voted time after time to approve every development placed on its agenda. There was never the sense that its members were making a choice – to fuel sprawl by shifting public investments to the suburban fringe rather than strengthen the urban core and maximize ng the public infrastructure already paid for there.

We took it as a hopeful sign that Mayor-elect Jim Strickland named neighborhood improvement as the topic for one of his transition committees, whose recommendations called for more direct involvement by city government in identifying the needs of neighborhoods, in setting metrics to determine impact of investments, improving poor customer service, breaking down current silos, and stimulating economic revitalization by attacking the problem of inadequate partnerships.

Suggestions For Neighborhoods

In particular, the community committee’s recommendations included these: “the City should establish and capitalize a new redevelopment fund comprised of city funds, private investment, grant funds, and other available national, state and local funds to assist non-profit and for-profit investors who seek to develop single family, multifamily and retail projects in identifiable neighborhoods that will accelerate demand and investment in Memphis,” and “the City should partner and assist in developing a strong and independent community enterprise development entity that partners with the City and charged with facilitating increased urban revitalization for both commercial and residential areas on a neighborhood identified basis, and which assumes the direct involvement in developments.”

The committee also talked about how words matter, and that rather than talking in negative terms like “blighted neighborhoods,” we should instead refer to “reinvestment zones.” In our vocabulary, we often suggest that core city neighborhoods – and the people living in them – are problems rather than vehicles for economic growth and higher revenues for city government.

As for the Klondike/Smokey City plan, its housing priorities were to identify and map blighted buildings and vacant lots, determine the need for various housing types, implement demonstration projects, construction infill single family homes for sale and rent, redevelop some vacant lots as open space, and construction in fill multi-family on Chelsea and Jackson

Commercial priorities were to develop the urban magnets, determine the real sustainable retail market need, recruit businesses that meet the real need, provide opportunities for neighborhood entrepreneurs, strengthen compatible existing businesses, and construction of infill business as market allows.

In addition, the Klondike/Smokey City plan’s “implementation strategies” are a good to-do list for almost every Memphis neighborhood: 1) Institute required policy changes, 2) Forge critical partnerships, 3) Identify potential financing options, 4) Suggest legislative actions, 5) Strengthen neighborhood association/CDCs, and 6) Implement Catalytic Projects.

The Front Of The Line

The good news is that there is growing support for more neighborhood investment and the best news is that there is a foundation to build on. It includes Memphis HOPE, Methodist Health Assets, Neighborhood Christian Center, Agape, LeBonheur’s nurse practitioners, GrowMemphis, Christ Community Center, Victorian Village training public housing residents as neighborhood docents, BRIDGES, Caritas Village, Community Development Council and its members, Community LIFT, numerous neighborhood associations fighting for the future, and more.

All of this is why Memphis needs a balanced program for the future. It’s about major projects but it’s also about neighborhood revitalization. We’ve concentrated for more than a decade on the former and it’s time to concentrate on the latter.

It’s time for neighborhoods to move to the front of the line.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.

Great article SMC.

Since Memphis has been chosen as one of the six Choice Neighborhoods Federal grant recipients, I think the City now has the chance to demonstrate their capacity and expertise to holistically revitalize the Foote homes area. In short, to follow your prescription.

That’s a 30 million dollar grant that can be used collaboratively with the residents towards the efforts that will invest in the neighborhoods in an effort to transform our city communities into places that can:

“recruit businesses that meet the real need, provide opportunities for neighborhood entrepreneurs, strengthen compatible existing businesses, and construction of infill business as market allows.”

If the City proves itself a good steward of that grant money perhaps that will open up other grant funding opportunities. My skeptical side thinks the area will simply be “transformed” into some newer mixed use housing units with little to no capacity for local economic development. I hope that my skeptic will be proven entirely wrong.

Great point, Aaron. South City should be made into the place that we take people when they ask to see a neighborhood that embodies our values and aspirations.

Thanks for pointing that out.

Thank you for your great article! “Neighborhood redevelopment” was the excuse to give a wealthy, out of town corporation a free $75 million hotel in Whitehaven at Graceland. What makes this taxpayer-funded freebie worse, Graceland will be competing against other hotels that actually have to pay for their own construction and expenses. Talk about government picking winners at the expense of others!

I would feel better about these ridiculous giveaways at taxpayer expense if we had not just elected a City Council member who voted for such largesse. Please keep up the good work pointing out these thefts at taxpayer expense.

It is very important to distinguish between Belz’s profit project which promises high rent apartments and maybe a high end store and the almost Great Society style Crosstown project. Confusing the nature and mission of the two projects is unfortunate. The very nature of Crosstown is to bring a wide range of backgrounds together: economiclly and racially diverse. It’s development of a higher calling fusing education, art, healthcare and the like.

Belz has acted in the worst possible way. At every turn blackmailing the city by saying if they did not build a fence or give a rebate they would walk away. Most shockingly they now say that the grocery which was the generator of the high sales tax figures may not be part of the project.

Not all tax breaks or the people that ask for them are equal.

Couldn’t agree more with Anonymous, for once. It is SHOCKING how poorly the Belz developer is treating Memphis. Would expect such greediness from Sidney Shlencker, but it is way beyond bad taste for him to be pulling such an egregious bait & switch. What’s far worse, though, is Memphis “leaders” still falling for such ’80s tricks.

Anonymous: Our intention was not to equate the projects, but simply to make the point that there are many projects that receive direct city funding of some kind while neighborhoods cannot get even modest amounts of investment.

Let’s also mention Peabody Place. A project built with an enormous about of tax payer dollars. Why has it spent years empty? Apartments are being built all over downtown. Why do we allow Belz to sit on a prime piece of downtown property? In its current state it sucks life and urban energy away from the area.

Why since we taxpayers paid for it is this fair.