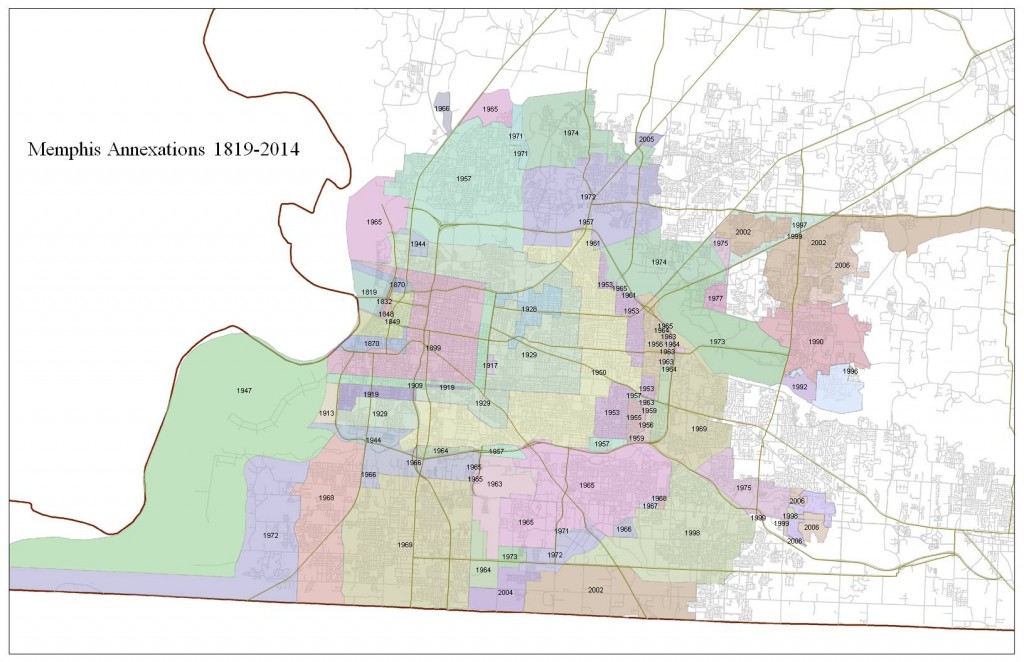

The following was published Sunday as a commentary to The Commercial Appeal’s landmark series this week on City of Memphis finances (thanks to Louise Mercuro for the annexation map):

By Tom Jones

Put simply, Memphis has too few people living on too much land.

The impact of that imbalance and the policies that created it ripple throughout the City of Memphis budget, increasing the cost of services, pitting quality of life investments like libraries and parks in a losing battle against climbing police costs, and requiring core city taxpayers to pay for a larger and larger Memphis while their own neighborhoods declined.

It is inarguable in hindsight that aggressive annexation by the city was not a race to prosperity as much as it set in motion dynamics that temporary stalled but ultimately deepened Memphis’s serious budget challenges. While it is easy today to see the pitfalls of increasing the size of Memphis by 60 percent while cutting its density in half, it is not as easy to dismiss city government’s rationale of chasing people and revenues through annexation, which was widely considered enlightened public policy by urbanists at the time.

Here’s the tale of the tape: in 1970 Memphis, the population was 619,757, and today, within those same city limits, the population is 449,930. In other words, the equivalent of the population of Chattanooga moved out, and they did it while the land area of Memphis grew to be twice as large as Atlanta, four times larger than Baltimore, and five times larger than St. Louis. Meanwhile, the densities of these cities are on average more than two times higher than Memphis.

The mismatch between size and density drove up the costs of services in many neighborhoods where more than half the people who used to live there were gone. In the inner city, poverty rates were as high as 60 percent in some census tracts, accompanied by dramatic declines in revenues at a time when services were being spread more thinly over an expanding area.

It’s no wonder that city officials were gripped by the belief that only annexation could deliver a much-needed burst of revenue. In this environment, the mandated analysis of revenues and expenditures as part of the annexation process was predestined to end up in the positive (and without considering what the impact of annexing new territory would have on the core city neighborhoods left behind).

Faced with financial challenges, it’s hard now to criticize city officials for not seeing better options, particularly in the face of Shelby County Government policies that were simultaneously undermining Memphis’s governmental and financial stability, including the decisions to send its debt skyrocketing to fuel sprawl and to deliver urban services to unincorporated areas of Shelby County.

As more and more people moved to sprawling areas where county government promised urban level services at a lower tax rate and to municipalities where Shelby County was subsidizing their lower tax rates with county tax money (which came largely from Memphians) for their services and roads, the City of Memphis felt under siege and with no choice but to chase people and tax revenues by annexing them into Memphis.

As a result, annexation decisions were never treated as choices — between paying for extending existing services to a larger area or making investments in core city neighborhoods. Even if Memphis had decided against future annexations in 1970, without major changes in county policies, it is hard to imagine that city government would not be financially stressed today, (not taking into account the impact of equally aggressive PILOT tax abatement program that waived about $350-400 million in city taxes over 10 years).

However, the most serious consequence from annexation was that it left city leaders with a false sense of security, and as a result, they never made smart city planning a priority nor mapped out an investment plan to keep older neighborhoods strong and healthy. In the wake of the “tiny towns” controversy in 1998, Shelby County, Memphis, and the municipalities had the chance to develop a smart growth plan for the future, but instead, they simply carved up Shelby County into annexation areas and called it successful.

In addition, City Council had power over all zoning within five miles of the city limits and power to extend sewer line, but never exercised either wisely. Germantown Parkway is a case study of one and Gray’s Creek development the other, but both speak to the single-minded allure of new revenues by adding more and more land.

The ultimate irony is that despite decades of annexation, most of Memphis’s sales tax and property tax revenues are today produced within Memphis’s city limits of 1970.

Tom Jones leads Smart City Consulting and edits the Smart City Memphis blog (smartcitymemphis.com).

so what’s some solutions? All I have heard is lop off some of the more affluent areas but I am not so sure that’s a viable solution. It seems like there could be other options, maybe some that have not been tried before.

Memphis needs to be a smaller city, but there are multiple legal, financial, and practical issues associated with that. We need to do the kind of serious analysis that tells us what the scenarios can be. Much more information, data, and analysis are needed before smart decisions can be made about what a smaller Memphis could potentially be.

The biggest mistake Memphis leaders made about 50 years ago was not consolidating the city and county into a single metropolitan government. Nashville and Davidson County did it then and have never faltered. Just look at the booming population growth and economy of Metro Nashvilke.

It’s worth remembering that the booming growth in Nashville took place 40 years after consolidation, but there’s no denying that its government structure has been a big plus for that city – more in attracting better candidates for mayor than anything. Of course, most cities have governments structured just like ours and they find ways to succeed. It leads one to believe that perhaps the mantra that “leadership is everything” is right.

If Memphis leaders had the power to consolidate, it would have been done already. There have been referenda to consolidate city and county governments in 1962 and 1971, and as you know, in 2010. You’d think the logic of merging two large urban governments with the same organizational structure would be glaringly obvious, but so far, it’s not been possible to get it passed by the voters.

Actually 99, Memphis leaders have supported consolidation every time we have had a referendum.

The opposition comes from 1) African American leaders who feel that consolidation will dilute their power and 2) County and suburban leaders thinking this is a takeover by Memphis.

99?

One referendum failed inside and outside of Memphis, maybe the one in 1971. In 2010, it barely passed in Memphis.

Your summary of the opposition is right on target.

You are so right about the lack of leadership in Memphis. Nashville has benefited from numerous progressive mayors who include Richard Fulton, Phil Bredesen, Bill Purcell and the current mayor is Karl Dean who has orchestrated the current huge boom in Nashville. Dean is nearing the end of his 2 terms as mayor and there are numerous excellent progressive contenders ready to continue the growth and development.. Hell would have to freeze over before such a scenario could happen in the good ole boy politics of Memphis and Shelby County.

This article is absolutely spot on! The only answer I see is de-annexation and allow the local communities to control their own fates. That will not happen. The other solution is to stop the bleeding by stopping the annexations and sprawl

Knoxville and Nashville have had much more growth than Memphis and Chattanooga. A largely unacknowledged factor may be that Memphis and Chattanooga are on the state line. The state line becomes a barrier that allows suburbanites to avoid paying taxes to either state or municipality while maintaining the economic benefits of living in proximity to a city.

Making Memphis smaller would help services that are spread too thin, but it would also decrease revenue. It seems that what really needs to happen is urban renewal. The city should give developers tax breaks to come in and build new neighborhoods where blighted ones now exsist. We need more residents to increase revenue from taxes.

Ann is correct.

FG

It is time to split Memphis up and let the new communities have community schools.

Ask anyone who studies this: young families buy schools- not houses.

There are neighborhoods in Memphis that could make it and eventually thrive as stand alone communities without the burden of the existing public school system.

The last thing I want to do is pay more taxes to Memphis.