The Brookings Institution, in a new report on the growth of extreme poverty in the U.S., wrote what we already know full well in the Memphis MSA: we’re at the top of the rankings. What’s more interesting is that it’s the trends in the suburbs that propel us there.

If there’s any wake-up call for the suburbs or for the proposition that we are all in this together, here it is: the concentrated poverty rate for the suburbs of the Memphis MSA is ranked #8 in the U.S. among 100 largest metros.

It’s the suburb’s high ranking that drives the Memphis MSA to #3 for concentrated poverty. The city of Memphis alone is #13 among the 100 largest cities.

Brookings wrote about extreme poverty (the fastest growing income group in America): “Rather than spread evenly, the poor tend to cluster and concentrate in certain neighborhoods or groups of neighborhoods within a community. Very poor neighborhoods face a whole host of challenges that come from concentrated disadvantage – from higher crime rates and poor health

Tale of the Tape

The good news is that the Memphis MSA wasn’t in the top 10 for regions where extreme-poverty neighborhoods increased the most in the past 10 years. It grew at 8.2% in Memphis, well behind the 14.5% in El Paso, 13.2% in Detroit, 15.3% in Toledo, and 12.2% in Jackson, MS. The bad news is that we didn’t record the significant increases of many other regions because there just wasn’t much more concentrated that our poverty could get.

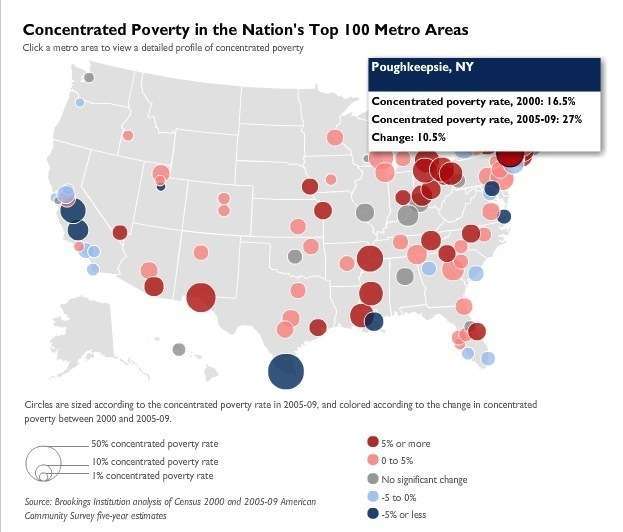

The Memphis MSA has 48 extreme-poverty census tracts (at least 40% of people living below poverty level) with a concentrated poverty rate of 27.7%. That compares to Nashville at 8.1%, Louisville at 16.9%, Atlanta at 6.4%, Birmingham at 10.9%, and Raleigh at 6.5%.

Our peer group includes Detroit, 23.6%; Milwaukee, 23.4%; Baton Rouge, 22.7%; Cleveland, 23.5%; Poughkeepsie, 27%; Jackson, MS, 22.7%, and Rochester, 22%. The only MSAs with concentrated poverty rates higher than Memphis are McAllen, TX, at 53.2% and El Paso at 34.9%.

The depth of the issue underscores the way that the problems of concentrated poverty are turbocharged here. While some cities are now grappling with this emerging issue, we have been wrestling with it for decades.

Sign On for Selfish Reasons

It’s also why if we’re talking about economic development and not talking about attacking poverty with the full resources of our region, we are merely engaging in delusion on a massive scale. As long as so many people are locked out of the economic mainstream, it keeps money out of our cash registers at the same time that the costs of public services to these troubled neighborhoods are increasing.

We’ve written many times since we started this blog more than six years ago about the cancer of economic segregation in our region. Hopefully, the Brookings Institution report will deliver that message with an exclamation mark. It’s encouraging that the Wharton Administration has been talking about how Memphis can become ground zero for imaginative, effective programs to reduce poverty, to give every child the opportunity to escape from it, and to develop the talent that is needed for today’s complex global economy.

It’s a tall order. It’s a daunting order. But we have stalled long enough and the consequences of inaction are becoming clearer and clearer. The new experiment to determine if monetary rewards can improve behaviors is well worth a try. The wrap-around social services that are needed to custom tailor interventions for each poor family are a step in the right direction. But, most of all, there must be a shared regional understanding that poverty is an enemy to all of our plans for a better future.

In other words, no one needs to sign up for moral reasons, religious reasons, or patriotic reasons. All of those might be motivation enough for many people, but all we need is a healthy dose of enlightened self-interest. In other words, let’s take the most selfish approach possible, because if we only care about what’s best for our businesses and our economic futures, we should urge every elected official in our region to put poverty as the overriding priority for our community.

And, So?

So, why does concentrated poverty matter?

According to Brookings, concentrated poverty can 1) limit educational opportunity – “children in high-poverty communities tend to go to neighborhood schools where nearly all the students are poor and at greater risk of failure..teachers in these schools tend to be less experienced, the student body more mobile…”, 2) can lead to increased crime rates and poor health outcomes; 3) can hinder wealth building – “neighborhood conditions can lead to the market to devalue these assets and deny them the ability to accumulate wealth through the appreciations of house prices, 4) can reduce private-sector investment and increase prices for goods and services; and 5) can raise costs for local government.

The report also contained a bad omen for Memphis MSA. “It is unlikely the nation has seen the end of poverty’s upward trend. Trends from the past decade strongly indicate that it is difficult to make progress against concentrated poverty while poverty itself is on the rise. It is also unlikely that without fundamental changes in how regions plan for things like land use, zoning, housing, and workforce and economic development that the growth of extreme poverty neighborhoods and concentrated poverty will abate.

“With cities and suburbs increasingly sharing in the challenges of concentrated poverty, regional economic development strategies must do more to encourage balanced growth with opportunities for workers up and down the economic ladder. Metropolitan leaders must also actively foster economic integration throughout their regions and forge stronger connections between poor neighborhoods and areas with better education and job opportunities, so that low-income residents are not left out or left behind in the effort to grow the regional economy.”

Do we have to keep saying things like:

“What we didn’t know was that it’s the trends in the suburbs that propel us there.”

We knew full well what was going to happen, it’s not an accident, this was done on purpose.

“Powered by who?” and “Why?” are the questions we need answered and especially:

“what are we going to do about them?”

“While some cities are now grappling with this emerging issue, we have been wrestling with it for decades.”

Exactly and that’s WHY we weren’t 31 in growth over the past ten years, we’ve been toped out and at full poverty maturity for that long. We don’t have that much more to grow, one look out the window when landing here in an airplane could tell you that with your own two eyes if they work properly.

To me, after spending 4 years in Memphis worst area and experiencing first hand what goes on there, I see it like this:

1. Concentrated populations of ex-offenders, ex-incarcerated, and mentally ill people are criminalized, which lowers the earning power of he community and destroys their saving power.

2. Once they are “in the system”, the concentrations of dysfunction create a culture of mental illness via protracted exposure to violence and poverty. This is multiple generations of people deep.

(see a map of crime, sex offenders, and domestic abuse and overlay that with an income map of the city and it will make sense to you)

3. In these communities, when there is not enough money for “relief”, then comes “escape”. Escape is drugs, alcohol, and finally when there’s no money for that, SEX.

4. Protracted periods of lousy educational resource distribution leaves the community ignorant over generations, criminalized, poor, escapist, and with no job skills, they will turn to prostitution, their concentrations will cause other known disorder effects.

5. Some smart business man will put up lots of liquor stores and pawn shops in their area, some corrupt police will run a burglary ring, some will control the drug business, calling the police will become a known taboo.

6. What’s missing?

E-F-F-E-C-T-I-V-E R-E-H-A-B-I-L-I-T-A-T-I-O-N.

Community rehabilitation programs with onsite psychological support, putting the right people behind bars for good and rehabilitating those who can be before it’s TOO LATE.

None of that has EVER been done here.

7. You probably want to know why I say effective rehabilitation is a key factor.

First hand experience in those neighborhood schools with unqualified teachers has shown me that almost 50% of all the kids in those schools have one parent in some stage of the “justice system” and many have BOTH parents in some stage of the system or is an ex-inmate.

Now remember, fly around the city in a plane an look at the ground, se how much of the geography is a ghetto, and do that math. If you don’t know the difference, go to a city where you can tell the difference and note it before you return to do your survey.

It’s the first thing people who move here see.

It’s VERY disconcerting, and a big reason why they leave.

This place has possibility, but, it NEVER realizes any of it, it talks a big story and never improves, THAT is what people take away from Memphis.

I know for a fact that you can create any future you want regardless of whether anyone agrees with you or not (it’s better when they do, but, not required).

This city never takes that responsibility up, It’s as if your people are trained to fight it with clique-ism, bureaucracy, belligerent ignorance, and a self centeredness/self defeating greediness I’ve never encountered to this degree, FROM TOP TO BOTTOM, in that Memphis is at one.

The needle on the desperation factor meter has been pegged so long that the gage is burned out.

You’re right of course. We have been writing here for years that the inevitability was obvious, but there’s been the strong denial outside Memphis that it was a Memphis problem. As we’ve often said, it’s a regional problem. We’ve said that it was coming – now it’s here.

Thanks for the thoughtful post and the insights. We do think that Memphis has no margin for error and that there are more positive things happening right now and the presence of leading national foundations working here are an opportunity we cannot squander. As you say, we need to turn the talk into action and change.

some of you will still be talking about the inevitable about Memphis losing its grip for the NEXT 25 years !

it’s not hard to understand why people leave, and really don’t wish to come here and stay ! why would you if you have at least six other good options ??

hate to break it to you, Memphis ‘squandered’ its future in the late 1970s and all through the 1980s

it’s doing the same thing now IF you can notice and actaully tell the damn truth about the region !

can it “recover” ?? I really have no faith or proof that it can or will ! maybe in the next 25-30 years ! but what dynamic thinking person or family wants to stick around for that “maybe” and gamble ??

I know too many people that will not do that to their families or careers, and I would never advise any younger professional to waste his very valuable time in such a competitive global environment ! again, WHY bother ??

Wow, once again such language and anger from someone who simply doesn’t get it and thinks others would share their narrow and uninformed opinion of Memphis, the world or life in general.

If you don’t have any faith in the region or think that anything positive can be done, why do you care enough to always be ranting about it?

Smart City do you think our region focus to much on the logistics industry? How can the Memphis metro area speak with one voice economically when much of the metro area is against Memphis?

I think the suburbs that are involved in the statistics are either primarily or entirely the suburban counties in the Memphis metro area rather than the suburbs in Shelby County. There is a lot of poverty in several of those suburban counties.

I know who that first anon post is. I’ve seen him in other forums and comment sections. He’s a straight up troll and has been banned by a few sites. I’d recognize that bad writing from anywhere.

Thanks, mtown85. We understand completely the decision to ban him. We’re close on that one ourselves.

Businessman, we think we’ve focused way too much on the logistics industry, committed way too much land and with much of it paying no taxes since they have tax freezes, poor salaries and overdependency on temporary workers to keep wages down, etc. And we sure don’t understand why we are giving PILOTs to them.

jcov40: Right. This was not suburbs in Shelby County but in all counties. As you know, that’s another reason we’re different from other places. You don’t leave the core city and drive out to high incomes and higher education. Generally, just the opposite.

@business man

that’s a point, and a good one ! residents of Memphis should wake up and face reality The reality is that all cities in the US are not destined for greatness and this applies to ALL cities, not just Memphis ! some cities will be left behind in the wake of others – there are and will continue to be winners and losers, and johnny come latelys – one city’s failure can be another city’s or region’s gain – it’s just that way – to suggest every region is entitled to enormous economic or cultural progressivism is pure nonsense. Growth and progressivism is a matter of degree – everything is relative. Memphis maybe relatively strong in some areas compared to others while at the same time being quite deficient to many others. Memphis doesn’t “deserve” anything that it has not worked for, and frankly its “work record” (compared to other cities) is very deficient- get over it

Some US cities are going to suck no matter what, and HAVE SUCKED for a very long time

Cities like Oakland, Jackson Mississippi, Birmingham AL (can you say BANKRUPTCY for Jefferson County TODAY ?), Montgomery AL, Newark NJ,

New London, Jonesboro AR, Pine Bluff, WEst Monroe/Shreveport, and a list of others across the nation.

Success is something you choose and work at over decades. Sorry to say but salvation was not meant or guaranteed for anyone or any city – That too is nonsense and folly. Salvation is seomthing you consciously and continuously SEEK. Plainly, Memphis has been and continues to be hampered in this quest.

You have to be in LA LA Land not to see that over time. Some cities might not be able to “make the trip”, and maybe, just maybe Memphis might be one of them – all the hope in the world won’t help – all of the false pride won’t help – all of the bravado won’t help – all of the denial and resentment of this fact of life won’t help. Being a realist might help though, in focusing on the areas of real possbile community success ! even if it’s only two areas, just be the best in those areas first ! success is contagious.

Memphis should get its collective head out of the clouds of urban design and false status, and truly FOCUS on what is the OBVIOUS problem and opportunity for the future.

All things flow from an educated electorate and community….period….but Memphis is one of the dumbest communites in which I have ever lived.

Memphis has no “shortage” however of useless religiosity and fatihful proclamation……and look what that has done for the city and region….NOTHING…..if anything, it has buttressed more ignorance and ostrich-like behavior for the entire social strata.

Imbedded racism, sneaky racism has killed Memphis, and it will be be resurrected and redeemed. It is the payback for being stupid all these years, while other cities blasted past Memphis and didn’t look back.

Memphis has made its own bed…now you are forced to lie in it. Blame yourselves – blame the locals – the natives – certainly not transplants like myself. Heck, I know better than to stick around a lost cause – a lost cause for at least another 20 years – yep, 20 YEARS at LEAST – if you have time to bask in the proposed “sunshine of accomplishment” TWENTY damn years from NOW, you go right ahead, and may God Bless you – but some of us may think you’re a chump.

also banning posters with whom you disagree says more about Memphis’ ability to really take a critical look at itself than any single poster..

banning any poster doesn’t enhance your status or opinion – it only puts Memphis’ lack of tolerance of opinion on continual display for others – it does NOTHING to the banned poster expressing a divergent opinion on Memphis. That, itself is crazy, parochial, and typical Memphis..

it’s crazy, now we have a cybergang mentality infecting the entire web on Memphis issues – everybody must buy-in to a singular voice about Memphis on any website at any time, and anyone who “dares” to diagree with “Memphis thought” is blamed for the lack of progress in Memphis over the years…

man, talk about ignorance, and backwoods “groupthink”…..

whew…….grow up Memphis…look, everyone is not the same, everyone in Memphis doesn’t think the same about Memphis or the region……everyone has a voice much to the dislike ot the Plantation Bossman…..

how primitive indeed ! Memphis is surely, somehow, brighter than this.

We’re not thinking about banning you because we disagree, but that’s probably the way you rationalize it in your mind. We’re thinking of it because you are robotic, monotonous, and boring.

“Memphis is surely, somehow, brighter than this.” That sounds like exactly the opposite of what you say ad nauseum.

No, face it and be intellectually honest ….you don’t LIKE WHAT I say it’s not because you believe it’s BORING

banning me, or others does nothing to advance your position

if everyoone is thinking the same, then someone is not thinking……..that’s true across this great diverse nation, with the exception of monolithic Plantation culture still impeding Memphis’ future…..

the fact that I, and others express the reality of divergent thought on Memphis simply irks you and others –

ban me ? you go right ahead, if you think that more censorship and unanimity of thought is what Memphis TN needs

if you choose to do that, that will provide clear evidence to others who do read your blog quite often, who are indeed looking at Memphis for a variety of reasons……some of whom I have spoken with at length about the true character of Plantation Memphis and its lack of competitiveness and forward thought……believe me, I won’t be “injured”…….you don’t even realize the damage that you are doing to yourselves even contemplating limiting reasonable free speech …..you don’t hurt me, pal.

the world-wide-web is a good thing to learn about the truth in any city- including Planatation Memphis

lots of readers of this blog and others formulate their own opinions about Memphis’ status – how you handle yourselves is far more important than how you handle my own reasonable posts, whether they are negative or positive…

We’re not trying to advance our position. We’re trying to have an adult conversation. You’re welcome to express any opinion you have if you could just once offer something factual or logical to back it up instead of the childish attempts to get attention. You can’t really think that somehow you are expressing opinions in ways that mature people do,

To your point, we have never limited reasonable free speech. Got anything reasonable, we’d love to hear it. There’s a first time for everything.

What a frigging crybaby. Wah, wah, wah. Any time anyone disagrees with him he immediately starts with the ad hominem “typical Memphis.” Shekel, you’re the pot calling the kettle black, and if you would stop repeating yourself with your bad grammar and insults, somebody might pay attention. DUH!

Shek, you’re not interested in intelligent or reasonable debate or conversation. If you were, you would’t make up crap about being a US Marine, or a rabbi, or pretend to be two different posters in the same thread who hold two different (equally stupid) opinions on a subject. You’re a troll, and only intersted in blather. My question is: if you hate Memphis so much, and everyone in it, especially poor black people, why do you spend so much enrgy and waste so much time and bandwidth obsessing over it. Seriously?

Reasonable posts? Who exactly is anon trying to convince- other readers or his/ herself?

Anon, not that you care (yet you do care seeing as you have gone out of your way time and again to tell us that you don’t), but your credibility per conversations with others is pure bunk. On second thought, I am sure you have made all sorts of outlandish comments to all sorts of people, yet the idea that any educated individual would take such opinions seriously is laughable. If said conversations were occurring I know that as an educated young professional myself, they would not give much weight to your rants having heard your other opinions concerning women, minorities, sexual orientation, etc… You deride the plantation yet your opinions all too often seem rooted in the era of plantations- the 19th century. Similarly, your attitude where the internet and forums such as SCM are concerned reflects a heightened degree of immaturity. You state that you are free to express an opinion (often personal) in regards to what others might post but simultaneously believe your opinion should be above similar critique or criticism. You think that eliminating a “troll” such as yourself is somehow indicative of censure because you cannot fathom that the freedom to post on such sites is accompanied hand in hand with the responsibility to ensure one’s posts should contribute to the conversation. In layman’s (or should I say Anon’s?) terms you are guilty of taking such freedom for granted and as often is the case are guilty of abusing such freedom. Despite your seemingly inaccurate claims of continued education and a supposed immeasurable depth of personal experience, you fail to grasp the most simple of concepts: that SCM is not a public domain. It was founded and is operated by private individuals who are in no way required to provide a platform for your irrational rants. Should you (God willing) be banned from this site, feel free to continue your obsessive dedication to informing those few with the time, lack of education or tolerance of your narrow minded and poorly informed view of the greater world around them. I’m sure that your habit for repeating the same stale and unsubstantiated opinions will do nothing but continue to betray whatever influence you dream of commanding.

Where is Zippy The Giver when you need him?

Undoubtedly, this same ‘anon’ is the person who has been banned countless times (under an array of screen names) from the City-Data forum. If nothing else, he’s determined.

looks like this whoever poster is just getting your skins for whatever reasons

move on, who cares ?

If anyone on this site thinks this is the only website with posters expressing negative or unfavorable opinions, they are living in a box !

There are lots of posters who are residents, or former residents of Memphis that express their own unfavorable but realistic opinions about Memphis, and city-data is just ONE ! so what ? sometimes you have the same paid posters who also sound like they are working for the local chamber of Commerce or the CVB as well.. Opinions are shaped by personal experiences and lots of people who have experienced Memphis have different opinions as well . That’s no big deal, unless you actually believe that Memphis is some sort of vanguard city when obviously it is not.

No matter though, why on earth get besides yourselves if someone else’s opinion and experience doesn’t support your own positive (or negative) position ? That’s crazy to get that personally in an uproar don’t you think ?

Funny thing, I lived in Las Colinas for a while, and there were people who expressed negativity about Dallas, but locals and residents don’t take the negative comments or opinions like they are talking about their mothers for chrissake ! in fact the criticisms didn’t seem to make them angry and nasty. That’s not the case about criticisms of Memphis , many seem waay too petty and angry.

I experienced the same sort of thing in Atlanta. No one cares to get viscerally angry in Atlanta if an outsider or transplant makes a negative comment about Atlanta. Both Atlanta and Dallas seen smarter than to get bogged down in trying to discredit simple possibly negative assessments or opinions.

The question should be why the vast difference between the reactions ? My answer is that Memphis might be still small-minded and an overgrown cotton town.

Anonymous:

Listen closely. No one cares if you are critical. If you’ve been paying attention, a lot of what we write about could be considered critical. What we care about is having a conversation as much as we can with rants, childish antics, and the same thing over and over and over. It’s a distraction and if you think that Memphis is all the things you say, why do you care so much to proliferate website with your pro forma rants?

We’re baffled by your comment about paid posters, and if you think that the comments are Chamber of Commerce-ish, we wonder why what we write doesn’t always please the folks over there. Stick to a logical thread instead of your hodge podge of unrelated bursts. You’d have more credence and impact.

Anon-

You inability to employ critical reading skills continues to hamper your ability to understand the articles an posts found at SCM. If you read closely, few are actually criticizing your opinions beyond your ability to support them with actual facts. What everyone- which apparently includes individuals in other forums- is criticizing is your disregard of the stated purpose of the site which is to formulate a healthy conversation pertaining to all aspects of life in Memphis and the region as covered by articles posted at SCM. One can only assume that you are suffering from some sort of selective reading disorder. Otherwise you would note that as many articles found on this site focus on the city’s negative aspects as do focus on the positive initiatives and momentum found both in the city and the area. Try as you might via misdirection, misinformation and your attempt to white wash your own posts by interjecting irrelevant comparisons, you still prove that your are incapable of participating in a discussion, are incapable of grasping the issues being discussed and are hindered by selective reading. I too have spent much time in Dallas and I can assure you no one living there (or anywhere else for that matter) would tolerate the degree of irrelevant and off topic rants you have posted at SCM to date beyond a knowing grin as they attempt to distance themselves from an obvious kook.

Summary: It is not your opinions. it is the way you bristle when individuals request or criticize your total lack of facts of experience on which you base your opinions. It is also the repetitious manner in which your rants are neither informative nor are they informed- they are simply blather from a misguided individual and no one anywhere (outside of certain mental hospitals) has a tolerance for as much.

SCM beat me to it.

now I see we’ve devolved into name-calling ! ha !

see what I mean ?

if you’re so damn-well informed…..in good ole Memphis, then why on earth is the place still so stupid and behind all these years ??

the point is that most of you are baying at the moon for the place to make significant strides forward.. you all seem to have been, and still ineffective as hell ! ha ha ! look around you, listen, look at the history

you want to influence somebody that counts ? get off the damn web and spend your precious and informed time and wisdom on the LOCALS, pal…they are the ones who sorely need you enlightened ‘leadership’ ha ha !

bitching about posters on a website is futile, er, if you’ve noticed ! people are still going to express their own opinions time and time again, get used to it ! THERE are more things to worry about in Memphis than putting out fires on the web, and you sure as hell can’t change my years upon years of experience in Memphis (or anywhere else)

so let the name calling continue ! I shall still be laughing at you for being so easily hassled, and it’s extremely doubtful that I’m going to change my opinions just to “get along with you” or anything else..

another thing, hopefully you really don’t think I, a web poster,, am concerned about CREDENCE and IMPACT ???? geeezus, pal you must be kidding, right ?? who cares about CREDENCE and making a damn IMPACT on the web ?????????? that’s nutty indeed…

I’m going to go hit some balls in a bit……later perhaps…..

unbelievable ha ha !

Please excuse my continued contribution to this tangent, but it is saddening to think there is at least one individual so lacking in their ability to comprehend the written word.

Urbanut you need to get out more around Memphis

Most of the popluation will make you “sad”

you’re the only enlightrened one in the building

that’s what Memphis needs …your pedantic web contributions

Oh trust me anon- I’m on the streets of Memphis, specifically in neighborhoods inhabited mainly be individuals you have said in the past you despise due entirely to their ethnicity, more than you could know. I have found that even those that could be counted as the least informed still manage to ascertain more and communicate in a more eloquent manor than your best attempt to date.

To the idiot: You ask “who cares about CREDENCE and making a damn IMPACT on the web ?????????? that’s nutty indeed”

Self-diagnosis is a good thing and progress in your case. Nutty is right.