With so much wrong in the world and so much need in Memphis, it makes us sleep soundly at night knowing that some Memphis legislators and the Shelby County drug court judge are spending their time working to make Spice illegal.

The “herbal smoking mixture” produces a distinct high, and apparently that’s enough to set into motion State Rep. Ulysses Jones, State Senator Reginald Tate and Judge Tim Dwyer. It’s always curious how much emotion is provoked by the mention of marijuana, particularly when the real gateway drug, the one that produces the greatest problems and costs in the country, is alcohol?

There’s no mention in the media coverage of this push for state anti-Spice legislation that the herbal concoction is addictive, but when marijuana, even synthetic pot, is mentioned, the facts generally fly out the window (although we do admire Judge Dwyer’s emphasis on treatment options for addicts in his court).

There’s little question, at least here, that we’ve lost the war on drugs. In fact, it makes Afghanistan and Iraq look like a cakewalk. Even if we are supposed to believe that we should continue to pay billions every year for this unwinnable drug war, there is less and less reason to skirmish over marijuana.

Reefer Madness

The local news media continue to treat marijuana as if it’s 1973. A December 23, 2009, Commercial Appeal headline said: “Pot farm near University of Memphis tunneled beneath property.” It had all of the favorite elements – 23 plants (farms must be measured differently when it comes to pot), 30 pounds of marijuana and the customary inflated values given by law officers and left unquestioned by reporters.

And yet, it’s clear that the tide has turned and medicinal marijuana is the beachhead. In addition, states’ fiscal problems have driven some to look at legalizing marijuana for the sales tax revenues. It’s high time, because at this point, illegal marijuana hits both sides of public budgets – reducing revenues and increasing expenditures.

Early in the Obama Administration, there was hope that more rationality would be injected into drug laws and enforcement, but with the walls of economic and political crisis closing in on the Administration, there’s less and less chance of that happening. Meanwhile, here, we argue over something that approximates the effects of marijuana, and even if it’s made illegal, there will be other mixtures and chemical compounds to follow.

There is little concern about tough sentencing on drug offenses, because drug offenders are the raw material that keeps the prison-industrial complex humming. It is a factory benefiting prison builders, concessionaires, vendors, contractors and hundreds of thousands of politically-connected prison bureaucrats. There’s little wonder we have the world’s highest incarceration rate – 25% of prisoners worldwide compared to 5% of the population.

Politics of the Impractical

Thousands of nonviolent drug offenders are thrown into jail every year, helping to explain why 1 out of every 100 Americans is now in prison (there are more people in jail and prison in Shelby County that in about 15 state systems), and the cost is more than $100 billion a year, money that can’t be spent on schools, arts, health care or other crucial underfunded programs.

And yet, elected officials like ours stand before cameras to posture at regular intervals to call for getting tough on crime, complete with often draconian (and largely ineffectual) mandatory sentencing. It’s unsurprising that some of the tougher laws produced by special Congressional committees included representatives of companies like Corrections Company of America, which leads the privatization of prisons campaign and financially benefits directly from more prisoners for longer times.

It’s a direct line and at its end are almost 2 million kids with a parent in prison – an 82% increase over 15 years. But the breakdown ethnically is particularly revealing – 1 in 15 African-American children has a parent in prison, 1 in 42 Latino children and 1 in 111 Caucasian children. The number of African-American prisoners in prison has quadrupled since 1980, and if trends continue, one in three of black males can expect to do time.

Because 62% of parents in state prisoners and 84% of parents in federal prisoners are more than 100 miles from home, visits from children are few and far between, contributing to family breakdowns and dysfunction. (There are programs in a few enlightened states that are aimed at continuing the connection between family and children.)

Putting Health First

It’s no secret that sentences are longer for people arrested for driving while black or shoplifting while black or taking illegal drugs while black, and to underscore this problem, the states where African-Americans have the highest rates of incarceration are also states like South Dakota, Utah, Iowa, Vermont, Montana and Colorado that are hardly known for their black population.

Maybe, just maybe, the answer for these nonviolent drug offenders is to treat them as a public health problem rather than a public safety problem. It’s the worst-kept secret of the criminal justice system that drug abuse in middle-class communities is regularly treated as a public health problem while in minority communities, it’s a criminal justice issue, and we’re not even talking about the disparity in crack and cocaine penalties that spring straight from racial bias.

To compound their risks, poor defendants are generally represented by overworked (or inexperienced) public defenders in courts and defendants’ broken homes and poor neighborhood support systems lead position them as grist for the criminal court mill.

In a 12-year period, 82% of the increases in drug arrests and the cost of the national marijuana strategy averaged $4 billion a year.

Booming Support

It’s not just pot that gets the overwrought media treatment that contributes to an overemphasis on marijuana, with reporters parroting without question the talking points of law officers and prosecutors. According to a guest speaker from St Louis addiction counseling services, in this regard, meth has become the new marijuana. There are headlines about an epidemic (about 0.2% of Americans have used meth) and apocalyptic statements by justice officials (one time use is instant addiction) as they ask for harsh mandatory sentencing. Based on media hysteria, it’s hard to remember at times that meth is one of the least-used drugs and studies in Tennessee, Texas, Iowa and California indicated that two-thirds of users are meth-free after therapy.

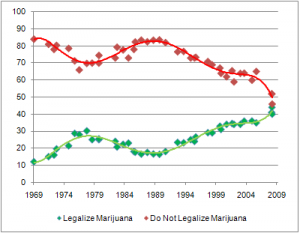

Back to marijuana: Support for legalizing pot stems especially from baby boomers who have experienced it. And most boomers know that they tried only marijuana. They didn’t try cocaine, heroin and acid, so by and large, this demographic is also skeptical about sensationalized reporting about pot or that it is the first stop on the road to ruin from hard-core drugs.

That’s not to say that the present boomers aren’t arguing with their 1960s selves. They may know there is no such thing as reefer madness, but despite that, they take a much more conservative approach to legalizing marijuana for their children (or grandchildren), but all the while, these kids have access to tobacco and alcohol. Of course, it might be easier for these young people to get marijuana, since unlike the legal drugs, they’re not regulated to keep them away from minors.

Unlike tobacco and alcohol, however, there’s no sales tax or sin tax on marijuana, and the hypocrisy about stimulants and addictive substances does nothing so much as cost states a lot of money. Marijuana is said to be California’s largest cash crop with revenues of $14 billion a year. In other words, a 15% tax would yield $2.1 billion in revenues for the state coffers, not even counting the benefits from the jobs that would be created.

The Right Question

In a sentence, the cost of criminalizing marijuana is simply not sustainable.

The costs are climbing and public revenues are dwindling. And research shows that European countries with much stricter drug laws than the Netherlands don’t have lower drug use, and if you’ve ever visited one of the bulldog coffee shops in Amsterdam that sell pot and hashish, it’s hard to distinguish it from an American bar serving alcohol.

In the past, the question was “why should marijuana be legal?” For us, the question now is “why should it be illegal?”

Good piece, but we’ll never see the end of fear-mongering.