Two years ago, when most attention was focused on the Nathan Bedford Forrest statue in a prominent city park in the center of the University of Tennessee Health Sciences campus, we raised an issue about all the Confederate detritus – including a statue of the president of the Confederacy Jefferson Davis – in an even more prominent park – one downtown on Memphis’ most prominent bluff overlooking the Mississippi River.

We have been pleased with the increased attention to deal with the Davis statue, and especially the leadership provided by Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland and Memphis City Council – who have now been joined by Shelby County Mayor Mark Luttrell and the County Board of Commissioners – in calling for removal of the two statues. It is hard to think of an issue that has so galvanized the political class in Memphis and Shelby County, and here’s hope that the state historical commission will take notice and do the right thing. In particular, Mr. Strickland gets kudos for gathering the signatures of more than 150 faith leaders in our community to take a moral stand in supporting removal of the statues.

Here’s the thing: The dedication of the Jefferson Davis statue October 4, 1964, was obviously meant to portray a parallel universe in Memphis at the same time the civil rights movement was striking at the foundation of the Lost Cause myths of the Confederacy: segregation. Clearly, Memphis was on the wrong side of history. Three months before the statue dedication, the U.S. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, and two months earlier, the bodies of young civil rights workers Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner and James Chaney were found in an earthen dam 190 miles south of Memphis. Ten days after the Davis statue was erected, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. received the Nobel Prize for Peace, four years before he would be murdered in Memphis as he led protests in support of better working conditions and wages for African-American city sanitation workers.

Recently, I wrote an article for the mlk50.com website, “Confederates’ Lost Cause still cripples the South’s economy,” which places these statues and the Memphis history in the context of how “a direct line rungs from the Lost Cause to the reality of lost opportunity in much of the Deep South.”

Finally, I talked with Deidre Malone last week on her Internet interview program about these Confederate statues.

Here’s the blog post we wrote in July, 2015, to get the Jefferson Davis statue’s removal on our local agenda:

Now that we are intent on burying one racist artifact by sending Nathan Bedford Forrest back to the cemetery and shipping off his statue, can’t we also throw in the statue of Jefferson Davis in a downtown park as part of the deal?

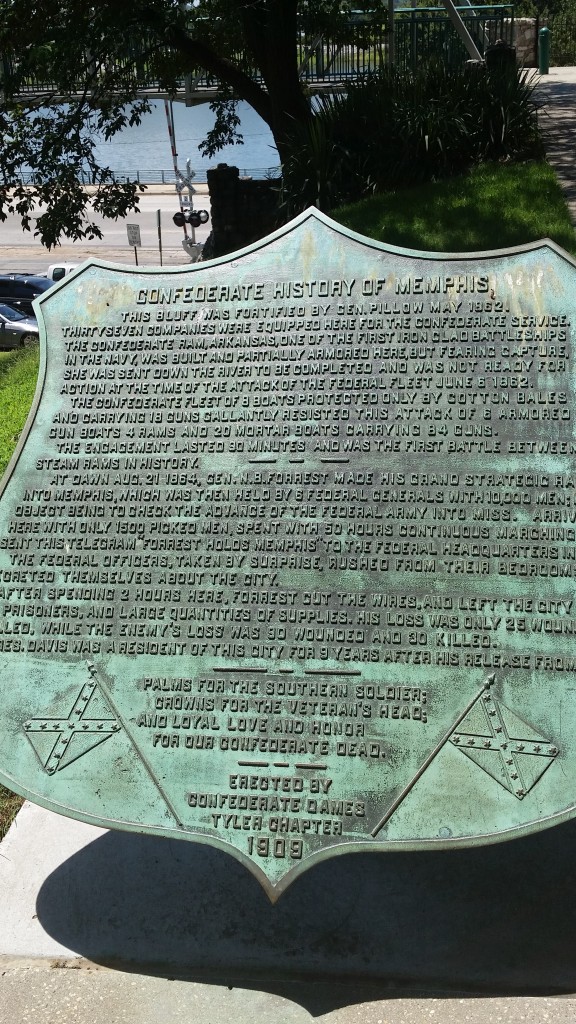

While the park has a new name – Memphis Park rather than Confederate Park – it still acts as the Rebel attic for a hodge podge of Confederate tributes, including the statue of the first and only president of the Confederate States of America. While most of Memphis’ Jim Crow monuments were put in place shortly after the 20th century began, the Davis statue was not erected until the 1960s as a direct response to the growing moral authority of the civil rights movement.

It’s a troubling reminder of the hostility and hatred tha lay at the heart of decisions to honor and keep honoring soldiers fighting to maintain an economy built on the backs of slave labor at slave labor camps, plantations painted over time with a brush of sentimentality and fiction.

It could almost be humorous to watch the pretzel logic exhibited by the defenders of the Confederacy, ranging from the South wasn’t really fighting for slavery, it was fighting for state’s rights (true, the right of the states to have slavery); the battle flag is just a tribute to the courage of these brave soldiers (in the same way the swastika is a tribute to the courage of German soldiers); this is about our heritage and history, not hate (although the heritage is hate and this isn’t about history – it’s about making up history); and these are our relatives and we don’t want them to be forgotten (our relatives also served in Confederate uniforms but we remember them as members of our family, not as heroes since it’s hard to work around the fact that they were fighting so people could remain property).

No One’s Laughing

But it’s not remotely funny. These monuments are ugly reminders how those in power use their white privilege to humiliate minorities, to pass laws that prevented black Americans from accumulating wealth, and to praise those who would have destroyed the United States as we know it today.

Strangely, in listening to the flimsy defenses of Confederate monuments, it is easy to come to conclusion that the defenders see themselves more as descendants of Confederates than as citizens of the United States, and as a result, they made the conscious choose to perpetuate the divisiveness of the Civil War and make their lives’ purpose the elevation of a lost, traitorous cause until it has no resemblance to the facts.

Apparently, it was in the pursuit of their revisionist history that someone in 1960s audaciously carved the following into the downtown statue of Jefferson Davis: “He was a true American patriot.” That the statue was erected in the same era that saw Dr. Martin Luther King’s murder in Memphis, and that even today, we have no statue of Dr. King speaks volumes on the power structure and its motivations at the time.

The statue was placed downtown six decades after Confederate Park was created. There is no mistaking its message.

Thumb In The Eye Of Unity

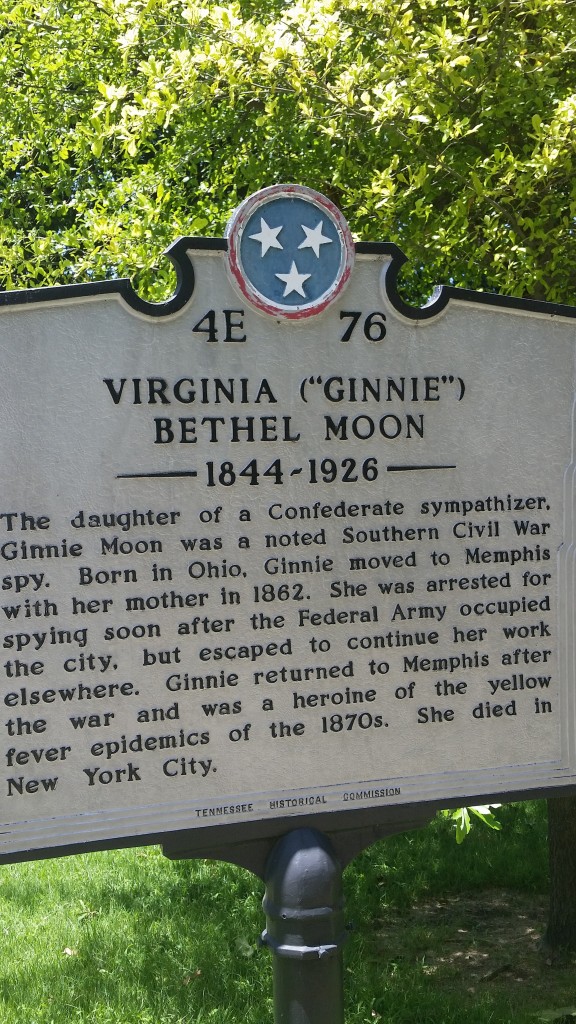

A friend told us this week that in a history of Memphis that he was reading recently, the explanation for Forrest Park was that in the first few years of the 1900s, Memphis had gotten its balance back after the devastating yellow fevers in 1878 and 1879 that resulted in 30,000 of the 50,000 Memphians fleeing the city. Of the 19,000 who stayed, 17,000 came down with yellow fever and 5,150 died.

Prior to the yellow fever epidemics, Memphis was home to large numbers of middle and upper middle families and a substantial underclass that had characterized it from its earliest days. During the epidemics, people with means moved, and by the end of the epidemics, it was poor African Americans, Irish, and others without means who were left here. (In fact, some of the “old” families in Atlanta, Nashville, and Cincinnati have roots that run deep to Memphis.)

With the dawning of the 20th century, the cause of yellow fever was determined, the city gained notoriety for inventing the modern sanitation system, and it started its road back. It is written that the city fathers wanted to drive a stake in the ground that said unmistakably that Memphis was back and that its future would be as a proud Southern city.

In that way, the Forrest statue and the naming of Confederate Park were ways that the message could be sent not just externally, but internally to let minorities know that although they had stuck with the city during its bleakest days, they should not get any big ideas that things had fundamentally changed.

Make The Park Worth The Trip

But that was then, and this is now.

If there is a place for the statue, the bust of Confederate captain, a history of Memphis during the Civil War, and a historic marker, it shouldn’t be downtown at the precise time that Memphis is trying to convince the world – and ourselves – that the city is not stuck in time or trapped by outdated, discredited historical events that have no relation to who we are today or the values that we have as a city.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.

For the reasons that the monuments must be removed, the same reasons demand that black people remove themselves from the Democratic Party. It is the party of slavery, white supremacy, and segregation. When will blacks completely divest themselves from the party of the Old Confederacy? Segregation and Jim Crow were promulgated by the Democrats. The Klan emanated from the Democratic Party. Remember, Davis, Lee and Forrest were Democrats.

So you want African Americans to be politically homeless. There’s sure no place for them in today’s Republican Party.

I completely agree with removing both the Forrest statue and the Jefferson Davis statue. With regard to the Jefferson Davis statute, it has no historical connection or relevance to the park in which it is located, so it can either be sold as scrap (or crap) metal or given to somebody who wants it. While we’re cleaning up that park, we ought to remove all the other irrelevant dreck which our City fathers over the years have allowed to accumulate there.

Here’s a thought – after we remove the statute, why don’t we acknowledge the real historic role that park played in Memphis history by renaming it “Battle of Memphis Park”. It was on that site that a large percentage of Memphians gathered to watch the Battle of Memphis and defeat of the Confederate navy on the Mississippi River. Keep the cannons and give the park a truly representative name.