Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland is part of a growing coalition of mayors calling for more State of Tennessee funding support for public transportation.

It is a promising sign that modern public transit may finally get the attention it deserves on Capitol Hill, albeit it is never easy to predict decisions of the Tennessee Legislature, particularly on an issue that attracts the attention of the Koch Brothers and ALEC influence there.

Mayor Strickland’s reply was an emphatic “Yes!” when we asked if he’s involved in seeking state action on transit funding. With pressures on the city budget for pension liabilities, public safety, and quality of life, the mayor understands that to achieve a goal of more money for MATA, City of Memphis needs state support similar to that seen in many other cities of its size.

Public transit has been a top priority of the Middle Tennessee Mayors Caucus since its founding eight years ago, and it could usher in a new spirit of community if our suburban mayors followed the example there and stood with Mayor Strickland for a better funded MATA.

In a ranking of 72 major cities by Center for Neighborhood Technology, Nashville ranks #62, seven spots below Memphis at #55.

State Help Is Vital

Already, there are several funding ideas being circulated with the Haslam Administration and Tennessee Legislature, and Mayor Strickland and his staff are evaluating them in light of Memphis budget realities, the local political context, and the best options for long-term responses for MATA’s serious funding needs.

The Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce’s recommendations include a sales tax for transit, the local portion of the state’s tax on gas, special land value capture tax, new taxes on commercial parking, part of the hotel-motel tax, and a higher wheel tax. The Strickland Administration has been part of a process led by Innovate Memphis that will produce a white paper on public transit that is scheduled to be released within days.

Here’s the thing: State support is crucial for MATA to have the opportunity for a level of funding that allows it to provide better and more adequate service.

After all, public transit has been shortchanged for years as the powerful roadbuilding lobby has treated the budget of the Tennessee Department of Transportation budget as its own. As a result, state funding for public transit is in the bottom third in a ranking of funding by states for public transit.

Clearing State Hurdles

As Governor Bill Haslam prepares to submit a transportation plan that includes a state gas tax increase from 21.4 cents per gallon, an amount that has not changed for almost 30 years. So far, the governor has not said if he will earmark some of the increase for public transit if the tax increase is passed by the legislature.

A budgetary earmark would be a grand slam for public transit advocates, but the legislature’s approval would also be needed to allow local governments to use local option taxes as dedicated revenue sources for public transit.

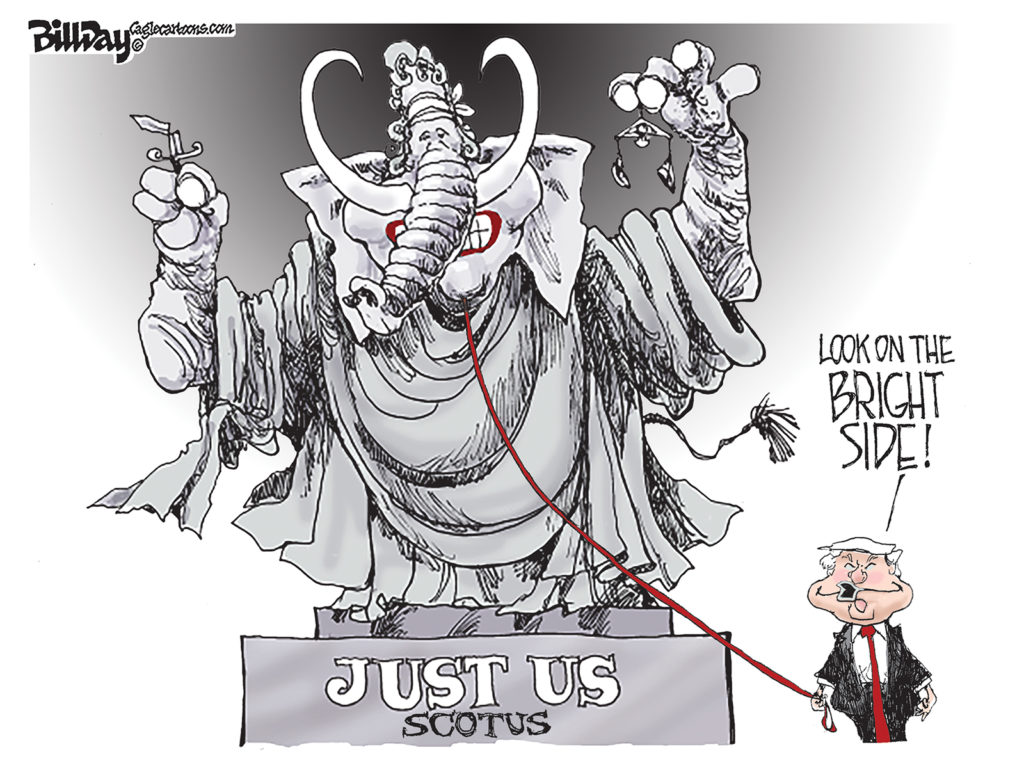

State legislative passage is a hurdle that may be difficult to clear, but with the Koch Brothers’ self-serving Americans for Prosperity’s opposition to anything that reduces sprawl and increases density, the odds are even more challenging.

The Tennessee Legislature’s interference in Nashville city government’s decision to create AMP, a seven-mile long Bus Rapid Transit project, is a cautionary tale, as the Kochs’ opposition defeated Nashville’s plan to reduce congestion and support sustainability. By the time the smoke cleared, Americans for Prosperity had enflamed racial and class divisions to get their way.

The hope is that through a broader coalition supporting smart public transit, cities can convince a legislature generally tone deaf to urban issues. As one Nashville transit supporter said: “They (legislators) talk about local control when it is about the federal government, but when it isn about cities, it is more about controlling the locals.”

More Money For The Basics

Mayor Strickland’s $667 million budget last year included $2.5 million more in the operating budget of MATA and a $5 million increase in capital spending as the MATA’s aging fleet requires replacement. The Memphis Bus Riders Union has ably chronicled the breakdowns and problems and advocated for better service. Some buses have logged more than 700,000 miles, about 200,000 more miles than the standard lifespan.

While MATA’s budget had not been cut in the years before the Strickland Administration took office, it had not kept pace with inflation, so last year’s increases signaled new City Hall intent to address an operating funding gap widely accepted to be about $20-25 million a year and capital needs of $25 million.

Acting on his promise to be “brilliant at the basics,” Mayor Strickland encouraged observers by including public transit among those basics. He said at the time: “It is essential that we have a solid transportation plan that allows people to get to work on time and helps the city recruit businesses to Memphis.” The attitude within City Hall about public transit under this administration is noticeably different – more collaborative and supportive – than in the past.

That he sees the potential of public transit as a business recruitment tool was a concept unspoken by his successors.

The failure of the current system to connect worker rich sections of Memphis to the job rich sites on the city’s fringes mandates that low-income Memphians buy cars to connect with employment opportunities, and as a result, Memphis leads the nation’s major cities in the percent of median household income spent on transportation: 27.3%

The Vision

In addition, efficient public transit is needed to address “transit deserts” that disconnect young people from educational opportunities, families from health and social services, and individuals from job training programs, to name just a few. Explaining the economic and personal costs of these transit deserts was pivotal in a campaign in Chicago that led to Cook County funding for public transit for the first time.

It will take time to create a more efficient public transit system, but to get there, we need a clearer vision of our destination. MATA President Ron Garrison has devoted much of his time since being appointed to painting a picture of what is possible and pushing the envelope on business as usual, but while that vision is clarified, there can be no argument that a better MATA is in all of our best interests.

Better transit was at the center of the Blueprint for Prosperity framework because of its impact in reducing household costs, reducing our carbon footprint, and providing alternatives for those who need them but those of us who also want them (as shown in the documents published in recent weeks by our blog).

The average household in Memphis spent more than $11,000 on transportation in a four-year period. As Scott Bernstein, president of Center for Neighborhood Technology, said during the Blueprint for Prosperity planning process: “This is money that can be better spent on education, small business investment, or any number of household needs.”

A Drain On Our Economy

Collectively, Memphis households spend almost $3 billion a year for transportation, and this is money that largely leaves our local economy. It adds up to more than $81 billion over the 30-years of the Long Range Transportation Plan.

In retrospect, it is nothing short of amazing – if not misleading – that these economic impacts are never discussed as part of our community discussions about public transit and better transportation planning. It also points out how much more attention we give to planning for transportation that carries boxes and freight than we do on transportation that carries people and families.

Just imagine what kind of modern regional public transit system we could create if we could only captured a small part of the $3 billion flowing out of Memphis every year.

Most of all, it would provide a brilliant service that’s one of the basics encouraging people to move to Memphis. It could propel the real estate industry, create jobs in transit-oriented development, improve workforce access, and fight disinvestment and overuse of tax breaks.

Alignment

All of this underscores why Memphis 3.0 is so important.

Our community has failed for decades to align transportation and land use, and the results are all around us from decades of public decisions made without the framework of a comprehensive plan. Changes in land use policy are vital if Memphis is to ensure that it uses its scarce resources most productively, increases density along transit corridors, increases ridership, and builds a stronger tax base.

To paraphrase the mayor, that is nothing short of being brilliant at the basics.

***

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.

I suspect that a legislature that makes the Bible our official state book and wants to add IN GOD WE TRUST to our license plates will not want to fund public transit because it helps poor and brown people.

Left out an important element: We are a region. MATA serves the region. Shelby County and the cities MATA serves must also contribute.

Also, planning decisions like Parkside at Shelby Farms build housing where there are neither jobs nor transit and exacerbate the problem.

can Parkside even be built before road improvements are made in that area?