We have an inviolate rule: we don’t argue with women who say something is sexist and we don’t argue with African-Americans who say something is racist.

They know it when they see it, and these days, African-Americans see it writ large in Sanford, Florida, and writ small with the rush here to create town school districts.

They know it when they see it because they have seen it often – the nuances, the clever justifications, and the dismissive attitude toward their concerns.

The killing of Trayvon Martin, the teenager armed with a package of Skittles who was gunned down in an Orlando suburb, is fast becoming today’s equivalent of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old African-American tortured and murdered in the Mississippi Delta in 1955 for allegedly flirting with a 21-year-old white woman. It was his murder and mutilation that are often cited as the pin prick that finally awoke Americans to the cancerous racism that flourished in our midst.

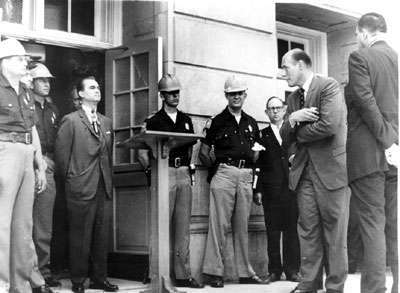

As for historical perspective, the push by the town mayors to wall off their schools seems akin to Alabama Governor George Wallace standing in the school house door in 1963. Of course, he talked about the role of the federal government and local political control of education. He stood in the door to keep African-American students out of the University of Alabama was to protect the special way of life that was under threat.

Our Way

It is this defense of “our way of life” that is central to the motivations of the town mayors to have their own schools and to make sure their cities are segregated from the rest of Shelby County. The language today is more polite and the justifications more politically correct, but the impulse is more basic and base. It is the impulse for the majority race to push back against the minority race and to overlay stereotypes and preconceived notions upon them in developing the political agenda and positions.

It has happened here for decades, but seems to be uglier in its political exercises these days, in the rhetoric of anti-Memphis opinions and the coarse code words, and in the willingness to point out the mote in others’ eyes rather than remove the plank from their own.

It exhibits itself in the town mayors’ inability to act as leaders who provide perspective and balance, but rather, as leaders who pander and play to the lowest common denominators of public opinion. It’s more and more a part of American political life these days, and local governments have been held up as the exception to the rule. That’s not the case here as the towns leaders can’t even manage occasionally to point out that it is the majority black urban city that drives our economy, holds most of our region’s jobs, pays for most quality of life amenities, and has subsidized suburban sprawl and the growth of the towns themselves.

Nationally, leaders call this a time for soul-searching, for introspection, and for self-examination. More to the point, it’s about engaging in an honest, candid discussion about who we are as a people and finding ways to contribute to productive conversations that end with a handshake and cooperation.

There’s no question that the same is needed here, but it requires suburban leaders to listen to the voices of Memphians without taking reflexive positions on the opposite side, without talking in code words, without remaining silence as citizens make outrageous claims, and without the apocalyptic rhetoric. The same is true for Memphis, but over the years, the multitude of regional initiatives has reached to the area outside Memphis but it’s a rare day when it is reciprocated.

The Decent People Should Stand Up

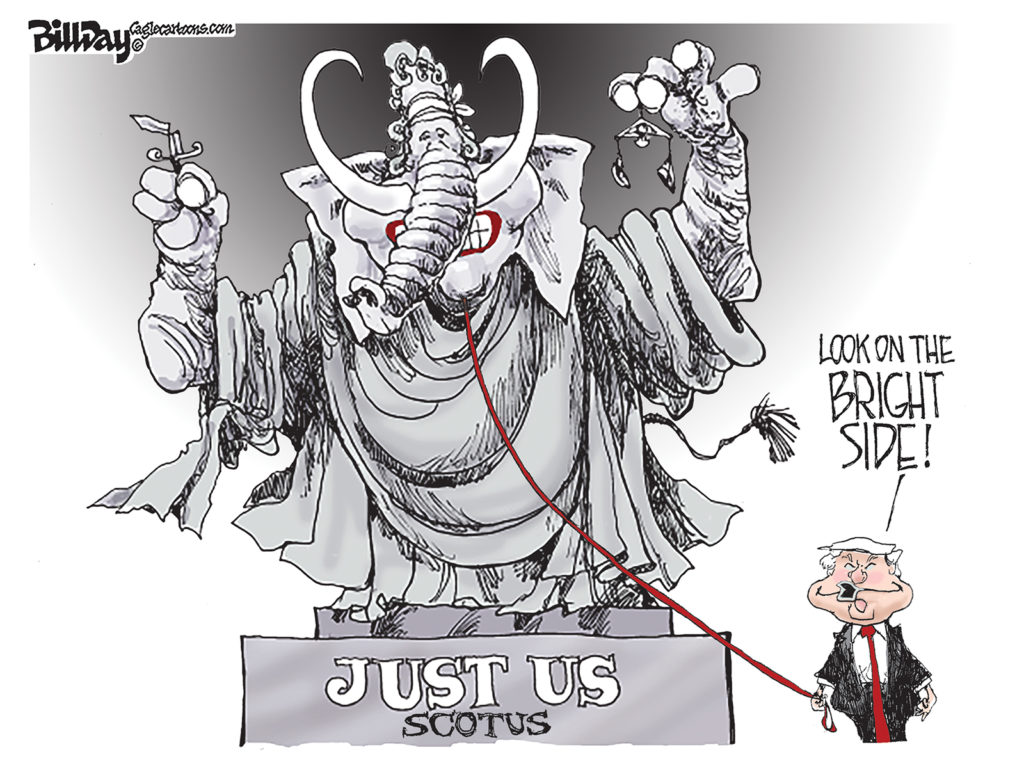

In fact, we cannot think of a single regionalism effort that ultimately accrued to Memphis’ benefit, and it is a trend that continues today with over-representation of suburban interests on groups like the Memphis-Shelby Growth Alliance and EDGE. The towns in the end are not looking for proportional representation or fairness. They are, as Shelby County Commissioner Terry Roland acknowledged in a refreshing burst of suburban candor, they are not content with anything but over-representation and imbalance on the side of their interests. It is this core motivation that propels so much that is advanced by the suburbs and by the legislators that serve this motivation with such blind devotion.

Despite this predictability, it is difficult for the majority residents of Memphis to hear much from the town mayors that isn’t filtered through a racial lens. The town mayors of course reject the fact that it is justified, and again, a group of white man (and one white woman) is willing to tell African-Americans that their opinions have no validity.

But, as we said when we began, African-Americans know it when they see it and they see it often outside Memphis.

Memphis Flyer reminded us of it last week in a letter to the editor, recounting the experience of a black woman from Memphis while visiting Bartlett was the target of hate speech and an uncaring Bartlett policeman unwilling to consider any action. Judging from the letters to the editor to The Commercial Appeal that are ubiquitous from that suburban town, it’s not an attitude uncommon in Bartlett.

The letter writer asked a seminal question for our times in this community: “Will the decent people please stand up?” The second question seems obvious to us: Is the mayor of Bartlett willing to lead those decent people in standing up?

don’t Take the Paycheck

Then there is that Bartlett High School graduate who serves as Arlington Mayor. Mike Wissman is another one of those Shelby County School Board members who holds two elected offices – something that has become common place for the county board members although suburban politicians were always willing to rail against John Ford when he double dipped.

Mr. Wissman often appears to be venting his deep hostility of Memphis and can reliably be counted on for some hyperbolic blast about why the city is going down the tubes. He appears to have a deep disdain for Memphis and is all about the Norris-Todd crowd sticking it to the city. It seems only logical that if he dislikes Memphis so much, he should refuse to take anything from Memphians, say, his paycheck as a Memphis firefighter.

Then there are legions of stories told by African-Americans about the seemingly relentless traffic stops by Germantown police on charges that can be lumped together under the heading of “driving while black.” There were also the expressed concerns from inside Germantown leadership that drove the county school board’s effort to move black students out of the town’s borders because the city’s schools were “becoming too black.”

There was the story by a national publication last year illustrating the anti-black attitudes of Americans. The quote was by a resident of Millington. There is also the long-time lack of city policy concern for the needs of its poor, a concern that normally has been dealt with by county government.

Collierville is the suburban town with a long history of African-American residents, although they were required to huddle on three or four streets which were the only place they could own or rent homes prior to changes in federal law. Old-timers who grew up in Collierville – like Mayor Stan Joyner – attended segregated schools through their entire 12 years there (his class was integrated in the last years of his high school education when a number of black students that you could count on one hand were admitted to Collierville High School. It is a non-diverse worldview that shapes the mayor’s policies and those of his political base and contributes to comments that sound sometimes close to standing in the door rhetoric.

Us Against Them

We suspect that neither this national moment of self-reflection about race nor the shared benefit of finding ways to unite this community will slow down the testosterone-fueled comments of the towns’ leaders or the “us against them” groupthink that passes for policy evaluation of the school issue. There’s little interest in setting guiding principles, gathering all the facts, sifting through all the finances, and considering all the options that achieve the educational goals.

The Transition Planning Committee has shown how it should be done, but this kind of thoughtful approach appears to hold little interest for town district advocates who decided what the conclusion was before they even began to gather information.

While it’s impossible for them to confront one of the driving forces of their runaway train, African-Americans can tell them all about it.