Note: My name is Joe Krattley. I’m a third year journalism student at the University of Minnesota. I want to say thank you to Bill Day as well as all the other political cartoonists who helped me with this story. I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed writing it.

Editor’s Note: Because the decline of newspaper cartoonists is a sad chapter in American journalism, I am publishing this story by Joe Krattley. It features former Commercial Appeal cartoonist Bill Day, who allows his work to be featured on this blog where he reminds us regularly that a picture – in his case, a cartoon – is worth a thousand words. His award-winning work is featured on the Smart City Memphis home page in the top right column.

**

Political cartoons are dying a slow death. The cartoonists who remain are doing what they can to keep them alive. Others have had to make what was once their job, a hobby.

by Joe Krattley

Every morning before going into work, political cartoonist Bill Day would sit in the parking lot for 10 to 15 minutes, bracing himself for the reality that it could be his last day with a job.

He hadn’t always had that habit. For much of his tenure at The Commercial Appeal in Memphis, he felt secure.

Part of the reason he left the Detroit Free Press for Memphis was because it felt safe. The paper had a cartoonist since 1916, going without one only if searching for someone new.

Even as more and more of his co-workers were laid off after the Great Recession of 2007, Day remained hopeful. After almost a century of having a cartoonist, he thought, surely they would keep him around. Yet on a March morning in 2009, 15 minutes into working on his sketches, Day got a call from his editor to meet at human resources. He knew what was coming.

Day and 24 of his co-workers were laid off.

“How am I going to survive?” was the first thing that went through Day’s mind.

Day was given three hours to pack up his office and go. He was never given an opportunity to get back the numerous drawings he was forced to leave behind.

“I took what I could, but in three hours what can you take?” Day said. “It was painful. But they didn’t care.”

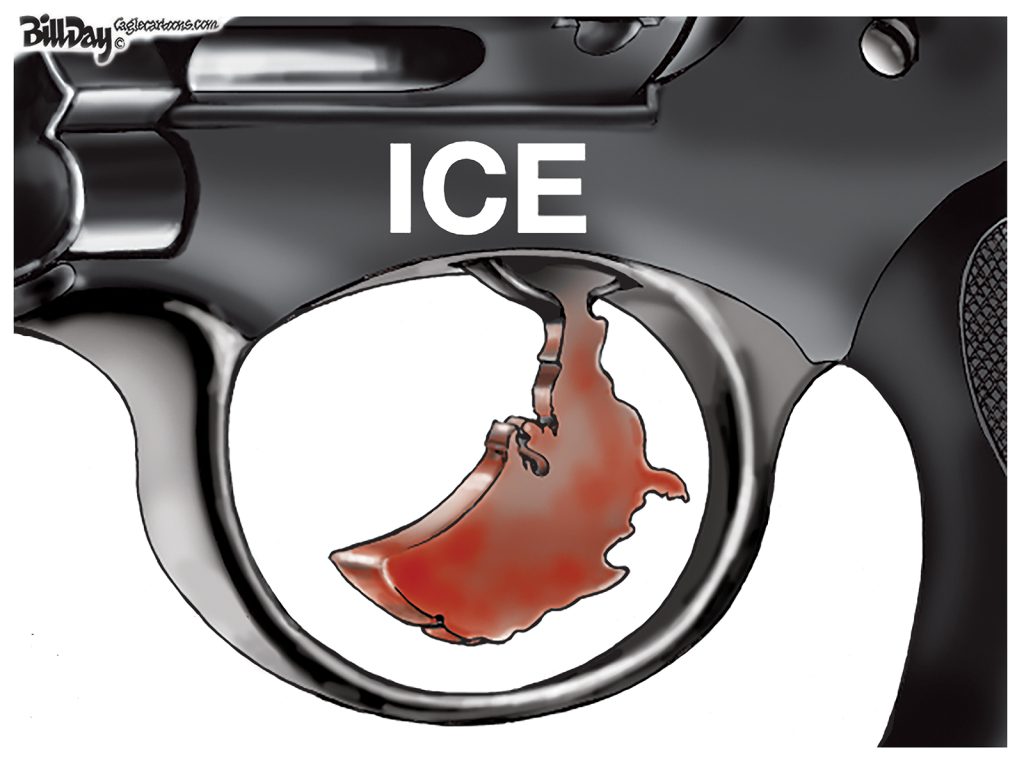

Practically every major news outlet used to dedicate a section of their publications to political cartoons. They were recognized as a powerful form of visual commentary that could distill any issue into a single, compelling image.

But the form has declined. It’s estimated that at the beginning of the 19th century there were around 2,000 editorial cartoonists. As of 2021 there were around 30.

The decline matches that of the newspaper industry as a whole. Daryl Cagle, an editorial cartoonist and the creator of Cagle Cartoons, one of the largest political cartoon syndicates, said that when he began his syndicate in the early 2000s, there were around 1400 daily newspapers. Now there are around 900, with that number continuing to drop as over 100 papers have shut down within the last year.

In June 2022, Gannett Media Co., the largest newspaper publisher in the U.S., announced that it was dropping opinion pages, where you most often find political cartoons, from its publications.

As of 2019 Gannett, now known as USA Today Co., owned 261 daily newspapers. After shutting down many, they now own around 100. Their publications make up over 10% of all daily newspapers in the U.S. Very few of them, if any, run political cartoons.

Outside of daily papers, the U.S. newspaper industry as a whole has shrunk drastically, losing over one-third of its papers since 2005.

As fewer papers publish cartoons and the number of defunct publications continues to rise, syndicates such as Cagle Cartoons become one of the only potential income sources for political cartoonists such as Day.

Syndication has always been important for cartoonists. But according to Day, for a long time cartoonists viewed syndication as an “extra” on top of the work they did for their staff positions. As these staff positions disappear, sending drawings to syndicates becomes the only option.

Day said cartoonists having to rely on syndication makes the field more competitive than it has ever been before.

“Cartoonists, they had the luxury of having their newspaper and could get along,” Day said. “But as they worry about who their reader’s going to be, as they worry about who their competition is, a lot of them have really pulled out their knives.”

Despite these trends, political cartoonist Scott Stantis was able to keep his full-time position at the Chicago Tribune up until 2019. A position he started in September of 2009 after 13 years cartooning at The Birmingham News.

Stantis was still drawing for the Chicago Tribune when he recalls having dinner with a friend who was heavily involved with the city’s politics.

As they sat and ate dinner, the friend remarked to Stantis that he wished his cartoons were still appearing in the Tribune. The comment took Stantis a moment to process, as his cartoons were still appearing in the Tribune.

For Stantis, this interaction was a sign of the decline of political cartoons.

“Someone like him should have known that, and he didn’t,” Stantis said. “That’s where we are in terms of the media landscape. It’s so fractured.”

Comparing modern news media to news media of even just 20 years ago, fractured is one of the best ways to describe it. Through the internet, everyone can now pick and choose where they get their news, as well as what news they want to be getting.

This has backed newspapers into a corner. The internet was once a niche environment for news while papers ruled the mainstream, a dynamic that has now been completely flipped, according to Cagle.

In April 2019, the international edition of the New York Times published a political cartoon depicting Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu as a seeing-eye dog for a blind President Donald Trump. The cartoon was seen as antisemitic, and the New York Times received international backlash.

In response, the Times discontinued all editorial cartoons in their international edition and fired their two in-house cartoonists.

This move from the Times reflected the ongoing decline in the prevalence of political cartoons, as well as an increase in sensitivity towards cartoons criticizing those in power.

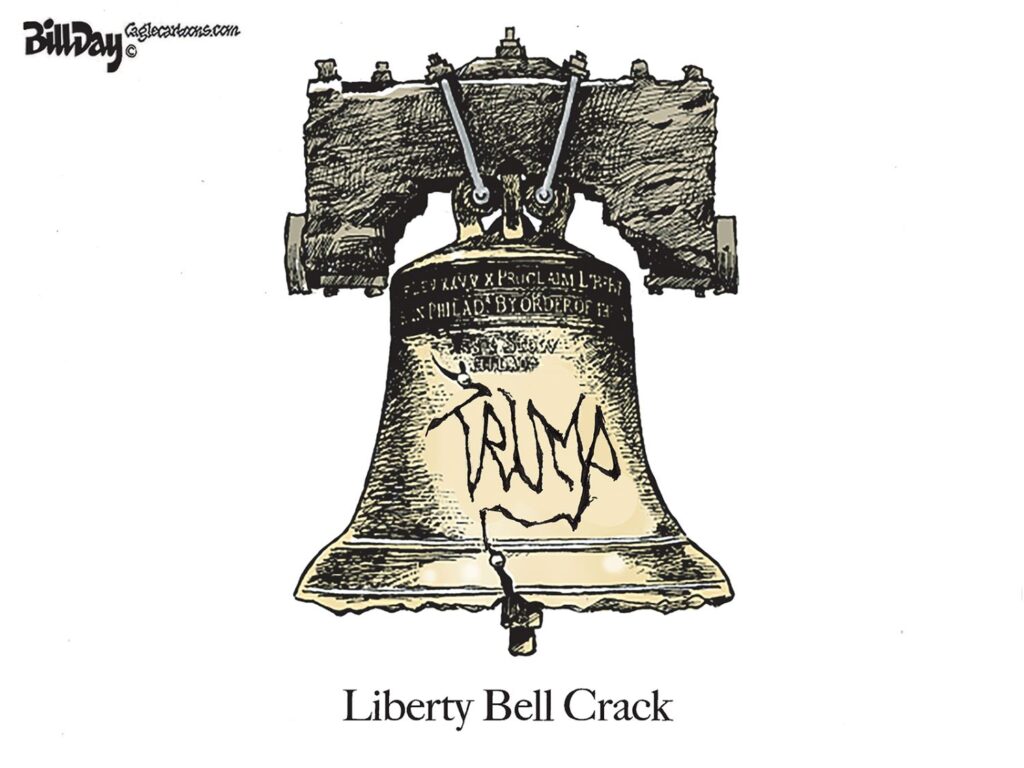

A sensitivity that Day says is largely due to Trump, his MAGA Movement, and the fear that the movement can strike into newspaper editors.

“The rise of MAGA has been very detrimental to editorial cartoons,” Day said. “Editors are afraid of losing their MAGA readers, and they’re afraid of the reaction that they get, because MAGA readers are easily offended.”

Earlier this year that sensitivity became explicit when Ann Telnaes resigned from the Washington Post over their refusal to publish a cartoon depicting Jeff Bezos alongside other billionaires bowing at the feet of Trump.

Cagle says despite offering hard-hitting cartoons to newspapers, oftentimes the most agreeable cartoons are the ones picked up for publication.

“You rarely see images of Donald Trump, and you rarely see cartoons that express strong opinions,” Cagle said in regards to the cartoons he sees published through his syndicate.

“A letter to the editor complaining about a cartoon has a lot of impact,” Cagle said.

Despite a push from editors for cartoons that won’t upset readers, Cagle says cartoonists continue to create cartoons that fight for justice and challenge power.

“Newspapers have become a niche content market for editorial cartoons,” Cagle said. “That hasn’t affected the work of the cartoonists who are doing great work without regard to supply and demand and without regard to whether the newspaper editors are printing it or not.”

Day credits his own editor’s timidity, in addition to his style of bold, critical cartoons, as large contributors to him being laid off.

“I believe a cartoon should make a statement,” Day said. “A lot of editors don’t want that to happen.”

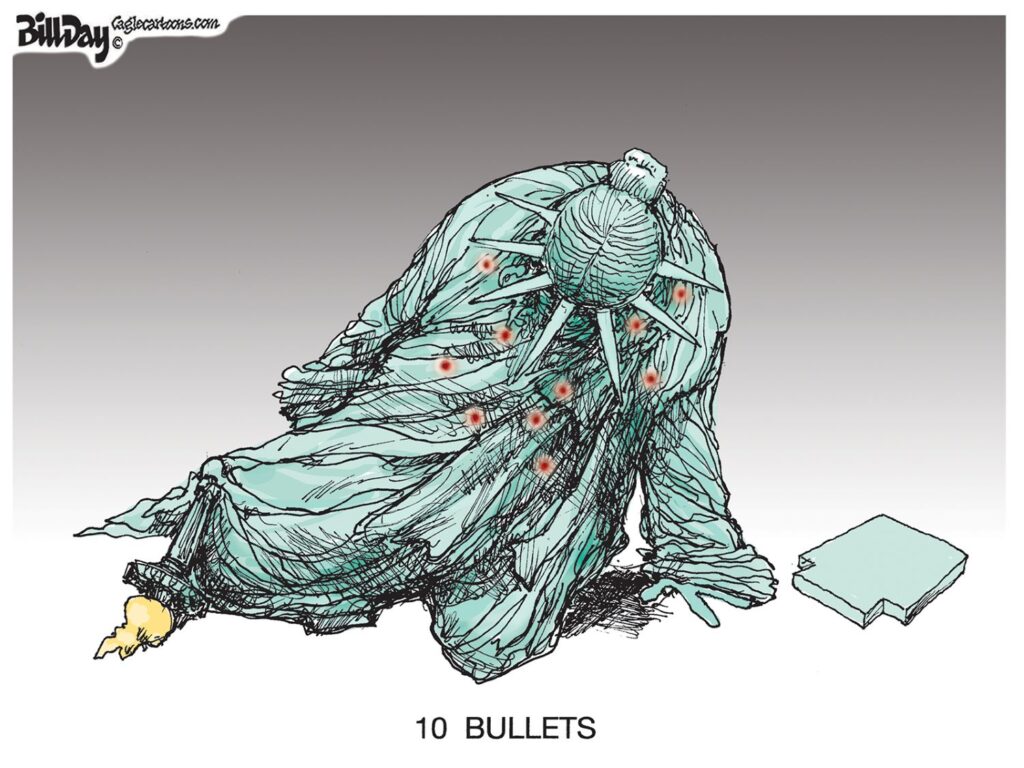

A “strong sense of social justice” developed as a child in the segregated South serves as the basis for many of the statements that appear in Day’s cartoons.

One night when Day was around 11 years old, he and his parents accidentally drove past a Klu Klux Klan cross burning, a memory that remains strong in his mind even 60 years later.

“The smell of it, the atmosphere of it was just frightening to me,” Day said. “That’s part of my upbringing. That’s part of the reason why I stand firm against the reactionary trends in this country.”

After losing his job at the Commercial Appeal, it would have been understandable for Day to put down the pen and find a new career path. But he persisted.

Even while working at a bicycle shop, then on the assembly line at FedEx, leaving political cartooning behind was never an option.

Even when odd jobs, freelancing and syndication weren’t enough, and his wife had to join the workforce to make ends meet, Day never stopped trying to get his message out to the world.

Day knows what he draws isn’t going to appeal to editors, or get him the most publications, that doesn’t matter to him. What matters is speaking his truth.

“They’re gonna do what they’re gonna do, I’m gonna be who I am,” Day said. “I’m gonna keep doing what I do until the day I die.”

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram where these blog posts are published along with occasional articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.