The singular failure of economic development plans in Memphis is their inability to reduce the poverty rate.

It’s really no surprise. While poverty is a dependable talking point in speech after speech, it often feels like a “check the box” point to make. Meanwhile, economic development plans themselves don’t include poverty reduction as a measurement of whether they are succeeding.

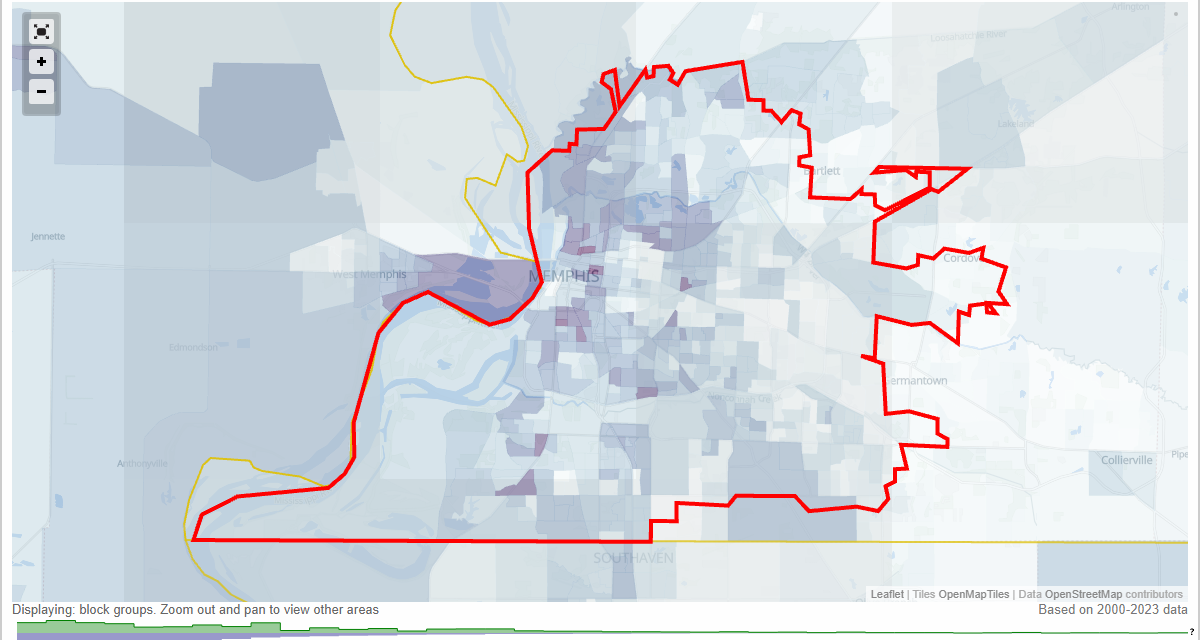

Regionalism appears to be once again on the agenda for economic development and before they think this diminishes the poverty issue as a challenge, they should think again. Among the MSAs with more than one million people, the Memphis MSA has the second highest poverty rate in the U.S. – 17.4% – and the highest rate of child poverty – 27.8%.

Put another way, 228,658 people live in poverty in our MSA. That’s about 30,000 more than the population of Chattanooga.

If there is a regional imperative more pressing than this, it’s hard to imagine what it is. After all, the #1 economic development opportunity for our region is closing the racial income gap to unlock a $29 billion increase in the GDP. That’s five times more than the $5.6 billion Blue Oval factory which received $900 million in incentives from state government.

Memphis’ Resistant Poverty

If regionalism is to be more effective than its previous incarnations, all of the counties in the MSA should care about reducing the poverty rate of Memphis. The late Phil Trenary said to me in when he was president of the Greater Memphis Chamber, “It’s not enough to reduce the poverty rate by people earning just enough to be above the poverty rate. That’s the mirage of progress. They have to make enough to raise their standard of living, improve their quality of life, pay for child care, and more.”

His words once again underscore the sense of loss from his 2018 murder in the city he so deeply loved and at the point that he was formulating an economic development agenda that would more directly set reducing poverty as a stated priority in economic development.

The challenge remains, as shown by the invaluable data from this year’s edition of Poverty Fact Sheet. This 14th edition of this indispensable report is once again researched and written by Dr. Elena Delavega, University of Memphis School of Social Work, and Dr. Gregory Blumenthal of GMBS Consulting.

They offer a straightforward and important assessment of what the 14 years of the poverty fact sheets tell us: “Over the course of our study of poverty in Memphis, the rates of poverty have remained resistant to significant change with minor increases and decreases from one year to the next…the controlling trends seem to be structural in nature and not cyclical.

“An interesting aspect of Memphis poverty is that it does not appear to be in sync with the rest of the nation. In 2024, poverty declined in the United States but it increased in Memphis. Why? It is clear from the data that poverty in Memphis is structural and that economic development is lagging in this community.”

There’s No Living Wage Here

The latest Poverty Fact Sheet reports that the 2024 poverty rate was 24%, compared to 22.6% just a year earlier. That’s an increase of 6.2%. It’s a 10% increase over 2019 when it was 21.7%.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, poverty has generally become worse. Since 2019, the poverty rate is up 10.6%, white poverty is up 16.1%, Black poverty is up 6.9%, and Hispanic poverty had increased 17.1%.

“Poverty in Memphis has increased since last year,” the authors of the Fact Sheet concluded. “This is true for most groups, including children and minorities but not for non-Hispanic whites in Shelby County although the poverty rate for non-Hispanic whites in the City of Memphis and in Shelby County increases significantly. It bears repeating that once again, the poverty in Memphis has increased even as the poverty rate in the United States has fallen.”

The U.S. poverty rate is 12.1%; for Tennessee, it is 13.5%; and 19% in Shelby County.

The report also said: “Implementing a living wage for Memphis is another policy solution that is long overdue (the minimum wage has not increased since 2009) and Tennessee does not have a minimum wage; the state depends on the minimum wage.”

In 2009, the federal minimum wage was increased from $6.55 an hour to $7.25 an hour. If the minimum wage increased at the rate of inflation, it would today be $11.31. Meanwhile, in this community, we operate under the myth that $15 an hour is a living wage. According to the MIT Living Wage Calculator, $15 is not even a living wage for one adult with no children. Rather, that living wage for a single person is $21.23 an hour and one adult and two children is $42.56.

Meanwhile, 42% of Black workers in Memphis earn less than $15. That compares to 19% of white workers. It’s little wonder that the fact sheet researchers conclude “the deeply entrenched racial disparity in poverty is an ongoing reality.”

Too Little Changes

When Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. led the sanitation workers’ strike, the median household income for white families in Shelby County was twice that of African-American families. Now, 57 years later, it is roughly the same. Media household income for whites in Shelby County is $94,971, compared to $47,180 for Black household income.

The Poverty Fact Sheet delivers a disturbing message about the intractable nature of poverty in our city and region. The Memphis MSA is #1 for the highest MSAs with more than one million in child poverty and #2 in the overall poverty rate.

Unlike many of its peer cities, as you drive away from the economic center – Shelby County – there are counties with similar challenges to Memphis. For example, the poverty rate for MSA counties are 31.4% for Tunica County; 20.6% for Crittenden County; 22.8% for Marshall County; and 16.8% for Tate County.

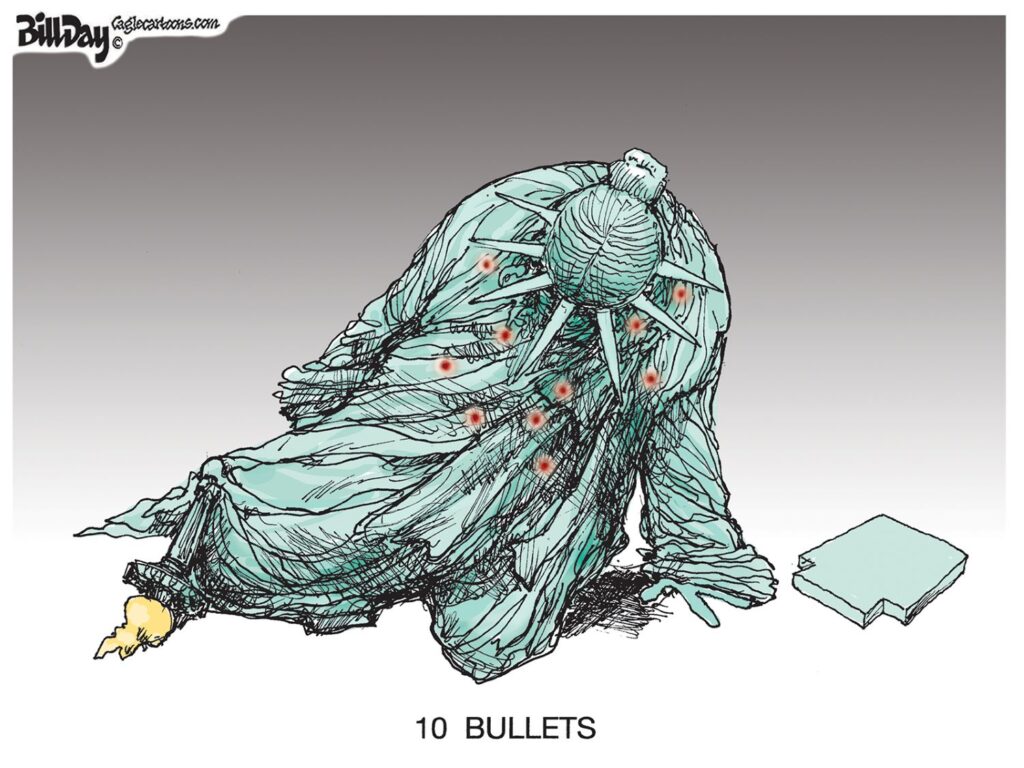

Year after year, there is no more disturbing statistic than the poverty rate for children in Memphis. In 2024, the child poverty rate is 31.3%, and it has increased in each of the past four years.

Expert Advice

The 2025 Poverty Fact Sheet provides a clarion call for solutions to addressing poverty. “One question the authors are asked all the time is ‘why is poverty so high among children?’ The simple answer is that children are poor because they have poor parents. The solutions to end child poverty are the solutions that help families thrive. Families need to be able to afford housing, and that often means programs to help low-income families buy their first home with a low interest rate; it means childcare support so families can afford to find and keep jobs; it means adequate public transportation that allows people arrive to work on time in a reasonable manner; it means funding education at adequate levels and insuring that all schools have what they need to succeed.

“Ending child poverty needs, above all, that parents receive adequate wages that allow them to meet all their family’s needs. The minimum wage has not increased from $7.25 per hour since 2009, sixteen years ago, and since the minimum serves as an anchor wage for all other wages, many people receive inadequate wages even when they have an education. When wages are insufficient to meet a family’s needs, is it any wonder that our community is suffering from such high levels of poverty and trauma?”

**

These commentaries are also posted on the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram along with occasional articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.

This was a great article on poverty – BUT it seems to miss the real point of the problem of poverty in Memphis. Both at the State and Federal level we have a strong pro-poverty set of policies. The supporters of the pro-poverty policies would claim that they are implementing pro-business policies — but even here, they tend to be short sighted pro-business policies. Low taxes and PILOTS ensure that remedial educational and social enhancement programs at the local level will never get beyond ‘pilot program’ levels. Federal lack of a real minimum wage, State hostility to living wages, and everyone’s hostility to trade unions guarantees that the current working poor will stay that way. And, of course, the historical impact of Jim Crow racism means that significant parts of the Black community are trapped in the intentional creation of a pro-poverty regime. It is probably time to stop writing articles like the one above — and recognize — that until there is political transformation at the State and Federal level — that not only will the poor always be with us, but, for some very sad reasons, we want it that way.

test