Memphian Carol Coletta, Bloomberg Public Innovation Fellow at Bloomberg Center for Public Innovation at Johns Hopkins University, was the keynote speaker June 3 at the Coalition of Urban and Metropolitan Universities’ Anchor Learning Network Action Summit. Her speech title was Connecting for success: New opportunities for economic mobility in the places you anchor.

Carol’s comments are always a master class about public space and its ability to create more happiness and more economic opportunity through its role in creating connections in our communities. As usual, she anchors her message in her hometown and her experiences as president/CEO of Memphis River Parks Partnership as it transformed five miles of Memphis riverfront with new parks and trails, culminating with the award-winning Tom Lee Park.

Here’s what she said:

Your institutions are under enormous pressure today, and when that happens, it’s natural to narrow your focus, “stay in your lane,” and adopt a crouch position. So my thanks to you for showing up today and leaning into the role you play as key drivers of opportunity beyond the campus in your communities and in our nation.

I want to tell you a story.

This is me holding a duck my dad brought back from a hunting trip. I’m standing in front of the home I grew up in. It’s in the South Memphis zip code 38106. My zip code is legendary for being home to Stax and Hi Records where Otis Redding, Isaac Hayes, Al Green and many others recorded music in the Sixties still heard all over the world.

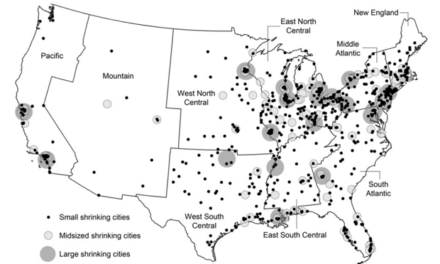

Today, 38106 is one of seven zip codes flanking downtown Memphis on the north and south that rank among the poorest in the state of Tennessee. One of them – 38126 – is one of the top 10 poorest zip codes in the country.

Fast forward to 2018 when I was working as a Senior Fellow in the American Cities Practice at the Kresge Foundation. Kresge loaned me to the public-private partnership in Memphis responsible for the development and management of a five-mile stretch of riverfront along the Mississippi.

Like many cities, the riverfront in Memphis is adjacent to downtown. But parts of the riverfront are only six blocks from one of the poorest zip codes in the country. In fact, it’s only a short bike ride from my childhood home in South Memphis.

So close, yet so far. So close geographically, but so far in terms of almost everything else. You could call it proximity without invitation.

You know this condition. You have likely experienced it along your campus boundaries. It’s one of the reasons this coalition exists. You are working to close the gap between town and gown. On the riverfront we were trying to close the gap between people living in distressed communities nearby and this public riverfront amenity that Memphians, without regard to income, all own a piece of.

Those of you in this coalition lift up your communities in so many important ways.

- The very heart of your mission is to educate talent, and that is critical community work.

- Some of you organize ways for students and faculty to form bonds with the community through internships, volunteer opportunities, and such.

- You provide jobs to your communities.

- Some of you provide employees with affordable housing.

- Some run K-12 schools and early childhood learning centers.

- You provide your community entertainment in the form of arts and sports.

- You unite communities by giving them something they can all cheer for and celebrate together… (something we need now more than ever)

- Many of you develop real estate in ways that physically link your institutions to their surrounding communities. In fact, some institutions have made intentional moves to open facilities in neighborhoods that need the jumpstart that an anchor institution can give them.

Coalition members should be applauded and celebrated for extending your resources to your communities. Bravo! You are our role models.

Now, I’m going to ask you to consider doing a little bit more.

You recall the proximity I showed you between the Memphis riverfront and the distressed zip codes nearby?

When I ran Memphis River Parks Partnership, we decided to capitalize on our proximity to those neighborhoods with so much poverty and distress AND downtown where the incomes were higher to create a riverfront for all.

Was it an obvious opportunity to create a more equitable riverfront? Absolutely! But it was more than that. It was a rare opportunity to create the foundation for the trust and social mobility we urgently need by using public space to foster cross-class connections.

What do I mean by cross-class connections? I mean loose-tie networks between people with high- and low socio-economic status… between people above and below the community’s median income.

These are not intimate relationships. They are not even what we would term as “close” friendships. Think about them as people who are connected on social media, show up at the same coffee shop regularly, participate in the same exercise group – people who are familiar enough to ask for and get a job or school or daycare referral.

That doesn’t sound like much, does it? Making what can be called a “loose-tie connection” probably doesn’t strike you as particularly significant.

But you might be surprised what a powerful effect these casual relationships … these loose-tie relationships… have on upward mobility.

Raj Chetty is a researcher at Harvard. He and his team at Opportunity Insights have been using big data to study barriers to economic and social mobility.

And what they found is this: At the community-level, cross-class connections impact social mobility more than anything else, including racial segregation, economic inequality, educational outcomes, and family structure.

Social mobility is at the core of the American promise – You expect your kids to live a better life than you’ve lived. Every generation will live a little bit better than the one before it.

But for many Americans, that is no longer the case.

Imagine an America where that promise is broken… where it’s no longer central to how we understand our future and our children’s future. That’s an America in decline… where a growing number of people lose hope of ever getting ahead.

How can we not feel urgent about creating more connections across income lines – either through greater economic integration of our institutions and neighborhoods or through more opportunities for cross-class social engagement – when it looks to be the most promising route to improving rates of upward social mobility in the U.S.?

Do we really have a choice?

But where do we make those connections today?

We are living in ever more income-segregated neighborhoods and sending our kids to ever more income-segregated schools. That makes it hard – really hard – for people of high and low socio-economic status – or let me use shorthand, rich people and poor people — to connect because there are fewer places they even occupy at the same time.

How do we even think about creating the conditions for social mobility and trust anchored in cross-class connections when rich people and poor people don’t regularly show up in the same places?

That’s where I believe your institutions can have big impact.

On the riverfront, we asked ourselves, “Can we play a role in knitting our community back together? Can we act with intention to create a space where high- and low-income people would find delight in being together? Can we use the low-risk of visiting public space to create loose-tie connections of high value?”

That seems like a question universities should also be asking, especially those of you here today who lead the community-serving strategies of your institutions.

How can a university deploy its resources to bring people across class together in ways that benefit everyone? And how can you do it with a minimum of effort and not a lot of money?

This is already part of your DNA in admissions and campus life. But can you use the same muscle to extend intentional mixing and socializing across income beyond the campus and into the community? Can you take inventory of your places, your people and your programs to see how they might be used to foster cross-class connections in your community?

Given that you are already in the business of social mobility, this should come more naturally to colleges and universities than it did to Memphis River Parks. After all, we were just trying to build and run parks.

But since we took mixing seriously, I want to modestly offer you some hints about principles that we and others –like your institutions –might use to bring people together who otherwise would be unlikely to meet.

Let me offer up seven principles we developed from our work to get the mix that matters.

The first principle is Allure. Allure is the quality of being powerfully and mysteriously attractive or fascinating.

I don’t believe you can force people to do what they don’t want to do for long. You have to seduce them into it.

For our 31-acre Tom Lee Park, we hired the best design team we could get to create a place so special that people with money couldn’t re-create it in their backyards and people with less money would think it was Disneyland. We attempted to do the same thing with programming – making it, at once, elevated and accessible.

It’s worked because we were able to maintain a great mix of people. This is what the income mix looked like with our first 100,000 visitors, and that’s remained steady almost 2 years later.

In the competition for students and faculty, you already use the principle of allure (although college administrators may not call it that). Think about how you can apply allure to create the gravitational pull you need to get your own mix right.

The second principle is Invitation. We wanted you to know you are invited to be there. The park shows that in a number of ways, but none more dramatically than the new access we built to the park, including a sweeping new ADA-accessible entrance down our steep bluff. Not only is it the first ADA-accessible way to get down the bluff, the new park entrance is only six blocks from 38126 – the zip code that is among the nation’s 10 poorest.

College campuses can be notoriously difficult to navigate for those who haven’t spent time as a student or employee. How can you make your campus more inviting to the first-time visitor? How do you help them navigate with confidence?

The third principle is Belonging. If we do our jobs right at the park, every person is greeted as they move through the space. We want the message to be clear: You are a neighbor here. Thus, the message on every uniform: Hi, Neighbor.

Our signage even tells you, first, what you can do: Make New Friends, Walk Your Dog. Then it tells you what you can’t do: Drink or sell alcohol or food without a permit, Tamper with the plants. We prioritize the welcome. Every person should know they are seen and that they have standing as neighbors in their parks (as long as they act in neighborly ways).

How can you make visitors feel like neighbors who belong in your spaces?

And speaking of acting in neighborly ways…

The fourth principle is Order. I know the broken windows theory is now suspect, but my experience tells me clean places tend to encourage behaviors that keep places clean. The same is true of safety. Places that feel safe tend to discourage unsafe behavior. We have to be intentional about creating the culture of a place… communicating with many overt and subtle cues the way we do things around here. If a place feels disorderly, unsafe or out of control, people who can be anywhere simply won’t come. And if they make that decision, you forego any chance of mixing across class.

We had multiple ways of keeping order in a public outdoor space with no gates and no locks, but my favorite was this guy: DJ Brother John. John Best became our official “Maker of Culture,” deejaying in the park during its busiest hours, setting the vibe with music – a great way to set a mood – and interspersing messages about “how we do things around here”… pointing out the trash cans, notifying people when it was time to rotate out of activity, simple, simple things. Brother John delivered a fun vibe that encouraged neighborly behavior.

So, yes, we believe in Order. But we also operate in Trust. That’s the fifth principle. Find ways to elevate people by demonstrating you trust them, even if it’s only with what feel like small gestures. We did it with free equipment loans. We loan a basketball, a hula hoop, a soccer or volleyball net, golf clubs and balls – whatever people need to enjoy the park to the fullest (including dog treats). We ask for a driver’s license in exchange for the equipment, but we will take your name and phone number if you don’t have ID.

Colleges and universities know a lot about “order,” so I don’t want to belabor that. But I don’t know what the analogue is in your world to building trust. I would be interested in hearing your thoughts on that since trust is in short supply today.

Principle six is Meaning. We were fortunate in Tom Lee Park to have a story of genuine heroism behind the park’s name. Tom Lee was a Black river worker who, despite the fact he couldn’t swim, saved 32 white engineers and their family members from drowning in the Mississippi River when their Corps of Engineers boat sank May 8, 1925. We didn’t have to make meaning. We just had to lift up Tom Lee’s story… which we did with an annual poetry contest and national spoken word commissions, commissioning new sculpture and a short film to use in classrooms, and constantly focusing on Tom Lee’s story.

We re-set an existing sculpture of the rescue into a beautiful new setting. Now it sits in the park in relationship to two exquisite pieces entitled “A Monument to Listening” by internationally recognized artist Theaster Gates.

The Tom Lee story gives meaning to the park that, again, elevates the park experience for all by celebrating a man whose “reward” for his heroism was a job as a City of Memphis sanitation worker – a man every park-goer can admire and whose story we know.

Colleges and universities have great meaning to your alumni. How can your institutions build meaning for others so that it becomes part of the invitation and helps others know they belong there, too?

The final principle is still unfolding and where our team at the Bloomberg Center of Public Innovation hopes to do a lot of learning, perhaps with some of you as partners. How can we Design, Program and Manage for Mixing if we want to be intentional about mixing people across class.

My approach is to do this with the thinnest possible layer of effort and money so that it can be sustained.

Think exercise class leaders asking participants to introduce themselves to the person on either side of them and tell them what gave them joy today. Anything to start a conversation… Designing a deck for parents to make new friends as they watch their kids on the playground or a porch full of Adirondack chairs for marveling with strangers at glorious sunsets over the Mississippi… creating Fire Pit Fridays where strangers huddle up with each other to roast their messy marshmallow and chocolate creations.

We did something right because 57% of people who visit the park say they met someone new. It doesn’t mean that new person turned into a loose tie. We weren’t able to measure that. But it’s a start.

As a Fellow at the Bloomberg Center for Public innovation, I get to spend the next two years learning more about how to get the mix we need to fuel trust and social mobility.

The research on the value of cross-class connections is very clear. Now, what we need to know is where and how these connections can be made. I hope one answer to the “where” will be on your campuses.

The Bloomberg Center of Public Innovation is forming a community of practice so we can quickly advance our knowledge of what works.

But each one of us here today should be very concerned about a nation where trust is stuck at 34% and social mobility is trending down. To date, Washington has tried big policy solutions that haven’t scaled due to their political, social and economic costs. And to be clear: I’m not opposed to trying other policy remedies.

But I’m suggesting that in the meantime, we begin in the places we occupy… the places we each influence.. and act with imagination and intention to normalize connections across class. If we do, the rewards for our communities – rich and poor alike – promise to be more than worth it.

At the heart of your work is helping people build better and richer lives. I’m hoping to get other institutions into that game — maybe some of your own– using this unconventional idea of building cross-class connections with whatever resources we have. And your resources are considerable.

Thank you for what you do every day to strengthen your communities.