Memphis has a history of being late to the latest urbanist trends, and the presence of Riverside Drive separating downtown from the riverfront is a perfect example.

While cities around the world are removing highways and opening up land for parks and green spaces, particularly alongside riverfronts, City Hall clings to the idea that the four lanes there actually makes sense.

We’ve gone through the data before but here it is in a nutshell: The traffic count on Riverside Drive is 29% lower than it was in 2001; the capacity for Riverside Drive is on average about 20,000 vehicles a day while the average traffic count is only about 13,000; and overall, downtown streets are significantly under capacity compared to 20 years ago.

Other cities don’t even need this kind of compelling evidence to remove highways. They do it to improve their cities’ livability and quality of life and in response to the now unassailable principle that cities are best seen and experienced from a pedestrian perspective rather than from a car.

We were thinking about this again recently when Owen Traw emailed a prescient commentary about the changes that Madrid, Spain, has made to improve the city by putting the interests of people ahead of cars.

Madrid Becomes Pedestrian-Friendly

In Madrid, the Manzanares River was completely neglected after two large spans of the M-30 freeway consumed its banks. Traffic was re-routed and the riverfront was redeveloped into a 300-acre park with running and biking trails, skate parks, recreation centers, 17 playgrounds, and an urban beach. Subsequent studies have shown that residents who live closer to the park and access it frequently are becoming healthier.

This presentation by so-called CityNerd Ray Delahanty is a good primer entitled, ” Making a Walking Paradise Out of a Car-Centric City.” The entire video is worth watching but what most interested me is at the 8:40 mark when he reports on the results of Madrid’s decision to remove a waterfront highway and turn it into a park.

Many cities have emulated Madrid. They have removed major highways along their waterfronts and through their downtowns to improve quality of life, to create places that are healthier, greener, and safer, and to replace them to produce “complete streets” that reconnect neighborhoods to the fabric of the cities.

Joe Cortright of City Observatory described the challenge this way: “We took an engineering view of cities, one in which we needed to optimize our transportation infrastructure to facilitate the flow of automobiles. The massive investments in freeways (and the rewriting of laws and culture on the use of the right of way) made cities safer for long-distance, high-speed – but at the same time produced massive sprawl, decentralization, and longer journeys, and eviscerated many previously robust city neighborhoods.”

University of Tennessee’s Ted Shelton and Amanda Gann of the architecture school wrote: “Where urban highway construction did occur, in urban design terms, it was highly detrimental to the urban fabric; creating physical and psychological rifts that are extremely difficult to bridge and introducing a substantial source of noise and air pollution. Cities across the country continue to struggle with this legacy.”

Finally, urban planner and Walkable City author Jeff Speck, after evaluating riverfront and downtown plans in Memphis, suggested an overriding principle for the city: “Don’t let traffic engineers determine your quality of life.”

Connectivity: The Lifeblood

More and more cities recognize the value of reclaiming land now devoted to asphalt and transforming it into parks, greenspace, and walking and biking trails. Many cities, including San Francisco, Boston, Philadelphia, and New Haven, Connecticut, have removed interstate highways and opened up land for residential and commercial development.

Highways were designed to move traffic rather than promoting a city’s economy or quality of life; however, research shows that when a high-capacity highway is removed, it does not produce gridlock on surface streets. Rather, “induced demand” shows that when streets are made bigger, more people use them, but when you make them smaller, people find other routes, traffic counts remain the same, and streets become more multifunctional.

Connectivity is the lifeblood of a high-functioning downtown and city, and many six-lane highways and interstates regularly disrupt the connectivity that comes when people are able to walk and bike easily from one part of the city to another.

Many cities – such as St. Louis, Kansas City, and Syracuse – have interstate highways built through downtowns and through the middle of their cities, displacing largely low-income communities, razing old buildings and homes, producing economic and racial segregation of neighborhoods, and increasing the amount of air and noise pollution and blight.

The damage is sometimes severe and when evaluated through a modern lens, the negative impact is clear, but old car-centric ideas die hard and it takes courageous leadership to say that some of them need to be removed.

The Asphalt Lobby

Politically powerful roadbuilding associations in state after state remain successful in lobbying politicians with talking points that “highways are economic arteries” and “every road is a good road,” and state DOTs routinely put engineering ahead of people and place.

Despite the documented benefits from highway removal, the preferences of city leaders are often trumped by state departments of transportation who often put moving cars regionally ahead of preserving the special quality of life for the city which gave birth to the region in the first place.

One key motivator for removing highways in other cities has been to enhance greenspace and activate parks. That’s what could be done if and when Memphis has a leader with a strong urban vision of how Memphis lives its best life.

What regularly happens here in the face of a national urban trend is that many people – too many people – say, well, that’s them; that won’t work in Memphis. As a result, we sit on the sidelines as cities that are our competitors make decisive moves to improve their livability and widen their competitive advantage with Memphis.

Portland, Oregon

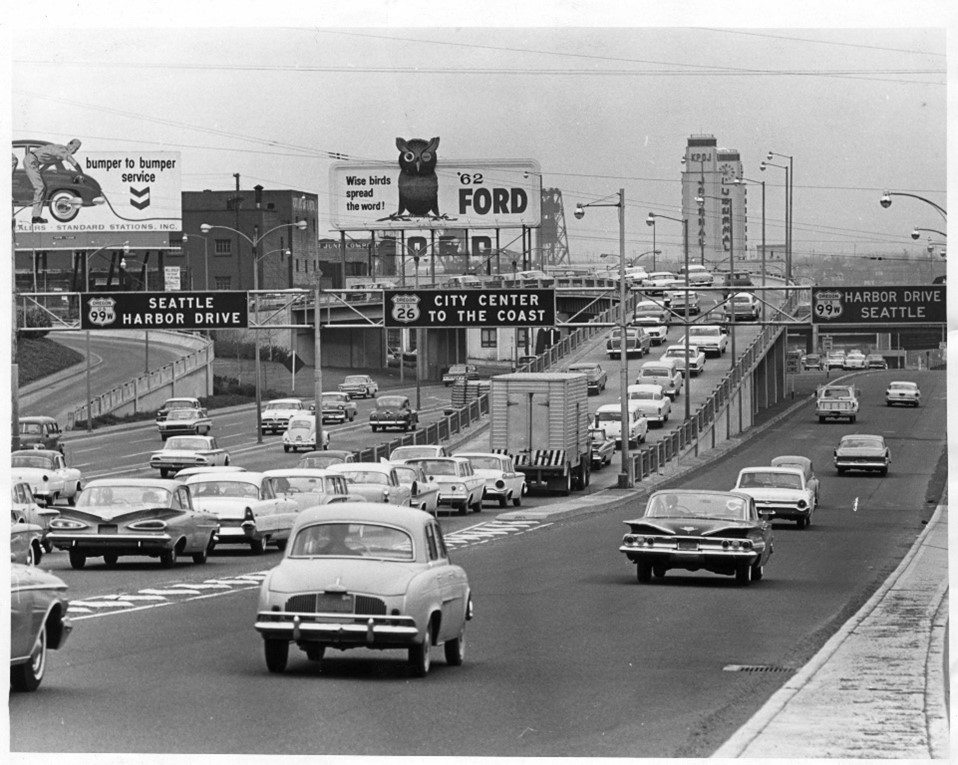

Portland’s Harbor Drive opened in 1943 as the original route of US 99W into downtown. It then crossed the Willamette River on the Broadway Bridge where it headed north on the Interstate Bridge and the city of Vancouver, Washington. By the 1950s, Harbor Drive was the first freeway to be completed in Portland and the only north-south freeway for over a decade. By 1966, I-5 on the east bank of the river was a  continuous freeway, making Harbor Drive obsolete.

continuous freeway, making Harbor Drive obsolete.

It was permanently closed on May 23, 1974. Construction soon began on 37-acre Waterfront Park, which opened in 1978, and today is a highly popular recreational hub. In the history of American freeways, Portland’s Harbor Drive holds a landmark position. It was the first major highway in America to be intentionally removed and not replaced. The removal, along with the cancellation of the planned Mt. Hood Freeway, established Portland’s reputation as a bicycle, pedestrian and transit-friendly city.

Boston

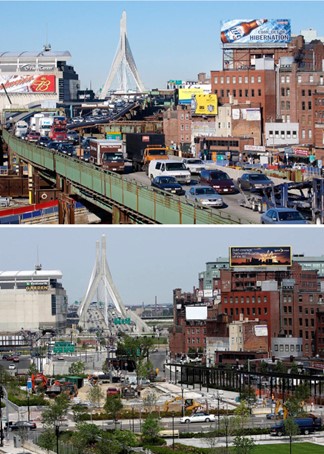

Boston’s legendary Central Artery/Tunnel Project (Big Dig) removed sections of I-89, putting parts of the interstate highway underground and creating more than 45 parks and public plazas on the surface. The project rerouted the Central Artery of I-93 through the  heart of the city into a 1.5 mile tunnel. In its place there is now the Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway, a linear park with landscaped gardens, promenades, plazas, fountains, art, food trucks, farmers’ markets, carousel, and specialty lighting systems that stretch through the Chinatown, Financial District, Waterfront, and North End neighborhoods.

heart of the city into a 1.5 mile tunnel. In its place there is now the Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway, a linear park with landscaped gardens, promenades, plazas, fountains, art, food trucks, farmers’ markets, carousel, and specialty lighting systems that stretch through the Chinatown, Financial District, Waterfront, and North End neighborhoods.

It is said that the greatest success of the Big Dig is that it established a new landscape for the city to flourish around it. Today, buildings that once overlooked a clogged highway have a beautiful park at their front doors, as shown in the following photograph.

(AP)

Milwaukee

The road plan for Milwaukee called for it to be completely surrounded by an interstate highway, and construction had actually started before opposition halted part of the highway from being built. In the 1990s, the city began development of a new three-mile Riverwalk system on the Milwaukee River and recognized that the Park East Freeway was a barrier to increased development so it was demolished, beginning in 2002.

McKinley Avenue replaced the interstate and renewal plans attracted new tenants and connected it to the new riverfront development, where population increased. Mixed use projects blossomed on both sides of the new boulevard, and Manpower Corporation moved its headquarters to the area, where the assessed land value grew by 45 percent. It converted an industrial corridor to an accessible and popular area for recreation, nightlife, performing arts, and dining.

McKinley Avenue replaced the interstate and renewal plans attracted new tenants and connected it to the new riverfront development, where population increased. Mixed use projects blossomed on both sides of the new boulevard, and Manpower Corporation moved its headquarters to the area, where the assessed land value grew by 45 percent. It converted an industrial corridor to an accessible and popular area for recreation, nightlife, performing arts, and dining.

(Journal Sentinel)

Chattanooga

In the late 1960s, Chattanooga built a waterfront freight route – a four-lane, limited-access, at-grade highway which did in fact move 20,000 vehicles a day, including industrial truck traffic; however, it denied easy access by residents to the riverfront and the highway stymied redevelopment of the area which is now the city’s most photographed area.

In the early 2000s, a plan was accepted to replace the highway with a more pedestrian-friendly and easily accessible boulevard. It was completed in 2004, increasing connectivity at four access points. Attractive sidewalks, gutters, plants, and trees as well as pedestrian crossing were installed to make it aesthetically pleasing. As a result, the area attracted new investment that revitalized the area and population has grown by 30% since 1990.

Philadelphia

Presently, Philadelphia is taking down the concrete ramps of I-95 between Market and Chestnut Streets and in its place will be an 11-acre landscaped park that provides a seamless, walkable link from Front Street in Old City down to the river’s edge. The $328.9 million project, led by PennDOT and the Delaware River Waterfront Corp, has been in the making for nearly a decade. The park will extend over I-95 and Columbus Boulevard, spanning north to south from Chestnut to Walnut streets. The amenities planned at the park include an ice rink, public gardens, memorials, play area, amphitheater, food trucks, cafe and a mass-timber pavilion.

Seoul

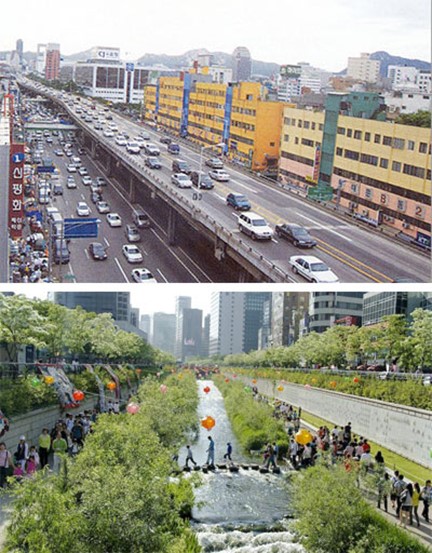

One of the most striking highway removal projects removed the Cheonggyecheon elevated highway that carried 150,000 cars a day in the center of Seoul and replaced it with two lanes on each side of the river. It not only did not cause a problem because of the city’s rich street grid, but its removal uncovered a lost waterway.

The elevated highway was built in 1976 on the basis of boosting economic development, but in 2003, the city mayor proposed its removal so the site could be turned into green space with the naturalized creek that once ran there. Today, the greenway is a well-loved part of the city. The temperature of the inner city has dropped, and birds, fish, and other wildlife have returned.

All in all, most of these projects make the removal of Riverside Drive seem elementary. But as these other cities have proven, before there’s any engineering plan, before there’s any budgeting, and before there’s a funding vote, there has to be a visionary mayor.

It remains to be seen if there’s such a person in the current race for Memphis mayor. Of will Memphis follow its normal pattern and take this step a decade or two from now, long after everyone else.

We are in the final stage of the extensive redesign of Tom Lee Park to make it the kind of people friendly, accommodating space your article mentions., However, I still believe there is a place for a grand public boulevard along the river to allow people to remain in their cars and drive down to get a sweeping view of the river without getting out of their cars. Also, this is Memphis, and not everybody wants to walk even a couple of blocks to get down to the river. The limited parking in the new Tom Lee Park will allow them to drive down as close to the Park as possible and not have to walk a long distance. Narrow down Riverside Drive to one lane each way and replace the landscaped median to slow down traffic, but keep the street in place.

If Riverside Drive was to become a slower, two-lane grand park-oriented boulevard rather than a highway that’s two lanes, I could live with that. I hear you about the parking, but it’s always astounding to me that when we visit other cities, we are willing to park and walk blocks and blocks to get to a great park, but in Memphis, we think we should park at the front door. Of course, there’s more than 1,000 parking spaces within a block of the new park, as I’ve written before and included the numbers.

Riverside Drive was closed during COVID and is currently closed again for the construction of Tom Lee Park. It is disappointing that Memphis isn’t willing to part with it yet. The current train of thought is to turn the outer lanes into parking if the political will manifests, but that still leaves Riverside Dr as wide and fast since I doubt adequate traffic calming would be installed in the parking lanes.