By John Branston

It was like meeting Mickey Mantle or Ike (President Eisenhower, for younger readers).

Elizabeth Eckford was 15 years old when she dared to integrate Central High School in Little Rock in 1957 and was darn near lynched for her courage. A news photo as iconic as Mickey Mouse or the young Elvis shows her in a white dress hugging her books to her chest as a swarm of screaming harridans curse her every step of the way.

As a boy growing up in the Fifties in a Midwestern family of Democrat news addicts, I saw it plenty of times and it left a powerful impression as I went into a news career in the South myself.

Holy cow, thought this lad who went to a big high school with exactly one Black student.

At a time of resegregation, racial division, fake news, bogus heroes, rude-and-crude and no news at all, it seems worthwhile to give Elizabeth Eckford another hearing. The Oxford American and the Memphis Library Foundation brought her here for two appearances this week. She was game, candid, alert, patient, classy, and compassionate toward friends, strangers and old foes alike.

“People in Little Rock can recognize me because I still have the same hair style I had back then,” she joked, later asking a photographer to please change the angle of his shot “because I have bad knees.” Her hair is short, she wears glasses (not the dark glasses she wore in the famous photo because of light sensitivity), pauses and gestures like a thespian, and seems to hold back a tear now and then as she recalls that horrible year.

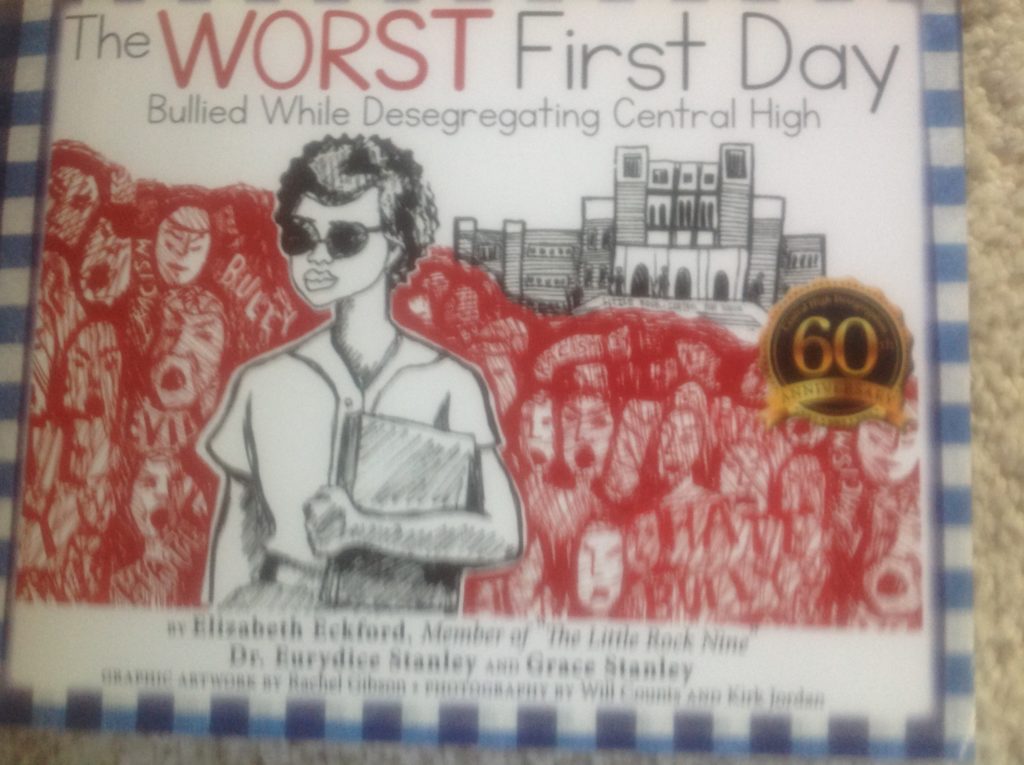

In 2018 she wrote a book titled “The Worst First Day: Bullied While Desegregating Central High” with a cover illustration by Rachel Gibson. It ought to be required reading in every book club, leadership conference and high school classroom in Shelby County. You think bullying is rude remarks on your Smartphone? You lead a charmed life.

This negro (her own word) girl had guts. She was a good student at an all-negro school in Little Rock when she and her parents signed up with 200 others for a chance to go to Central High, the 1600-student “best” of the city school system (under pressure it would not live up to that billing). Applicants had to be smart achievers and “not troublemakers.” Little did the 17 finalists know what they were getting into. Some dropped out when their names were published and their parents feared reprisals.

“Blood will run through the streets if negroes attempt to attend Central high,” Gov. Orval Faubus, a Trumper before Trump, warned the nation. He then cut and ran to insure his reelection in 1958.

“The Nine” had little solidarity. In fact they hardly knew one another, and Eckford, whose home did not have a phone, wound up alone her first day as parents were told not to escort their children despite the bath of blood Faubus promised. Reporters and cameramen swarmed her. On one side of her was the screaming mob, on the other side the equally hostile Arkansas National Guard wearing combat fatigues and carrying rifles.

“I soon realized they weren’t there to protect me,” Eckford wrote in the understatement of the year.

She saw an old lady who looked like a Grandma, but when she approached her for assistance, “Grandma” spit on her.

A crowd of girls/women (ladies is definitely not the word) followed her, screaming words that would make a rapper blush. A photographer snapped the soon-to-be world-famous picture. One of the screamers was named Hazel Bryan. In 1963 Bryan, then a mother herself and tired of being famous for her notoriety, phoned Eckford to apologize. Not wanting to be consumed by hate for the rest of her life, Eckford went along – for a while. In 1997 a “reconciliation” and photo shoot were arranged by some media-savvy people in Little Rock.

The feel-good story got a lot of play, but at the library talk Eckford gently scoffed at it and Bryan’s (then Hazel Massery) excuse of “amnesia.” She did not dwell on this or other phony stunts, preferring to urge listeners to “Walk Past Hate” and remember these words:

“Remember my first day at Central the next time you’re having a bad day at work or at school.

“It proves there is no limit to what can achieve despite naysayers who attack and berate.

“Know that I am extremely proud of you and always want you to go confidently with your head held high.”

**

John Branston wrote the first in-depth story of Memphis school integration, desegregation and resegregation and what came to be known as The Memphis 13 in a 1996 issue of Memphis magazine. It was republished in expanded form in his book Rowdy Memphis.

“