The following post is by friend and retired journalist John Branston and his sleep medicine specialist, Dr. Merrill Wise. It’s an unvarnished and moving account of a difficult personal journey by John, who has written for a variety of local and national publications. He also is author of What Katy Did, a book about his daughter’s suicide, and Rowdy Memphis: The South Unscripted, a collection of his columns. Themes in this article – grief, depression, angst, and exhaustion – are universal and addressed with honesty. This article is published in the current issue of Memphis magazine.

By John Branston and Dr. Merrill Wise

This story grew out of a nearly five-year quest to find something as old as The Book of Genesis. Adam “went into a deep sleep.” Many of the rest of us only wish we could.

A medical “case report” summarizes the details of an individual case. Healthcare professionals use it to illustrate diagnostic dilemmas or treatment challenges, and it is a time-honored approach to medical education. Case reports are usually presented in a standard format with medical jargon that can leave general readers scratching their heads.

The case report typically includes a few details about the patient’s life, but it almost never incorporates the patient’s experiences or perspective about his or her health or illness. Case studies often use only first names or initials to protect patient privacy.

“John’s Story” is a little different.

“The approach known as narrative medicine places the patient’s story at the center of the process and shifts the physician’s focus from the need to problem solve to the need to understand,” says Dr. Wise, a graduate of Rhodes College in Memphis and the University of Tennessee College of Medicine, with residency and fellowships at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

This three-part article begins with excerpts of Dr. Wise’s medical history notes over 18 months, followed by John’s first-person reporting and Dr. Wise’s narrative in layman’s language. The goal is to give readers a picture of the patient and doctor as people, rather than entries in a case report.

Traditional Medical History

From Dr. Wise: Patient is a 71-year-old gentleman who presented to sleep clinic for ongoing management of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome diagnosed at another sleep center two years earlier, and for evaluation of several other sleep issues. His initial diagnostic sleep study showed evidence of mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea (note: a common sleep disorder with recurrent upper airway obstruction). Treatment with nasal CPAP was recommended. (Note: continuous positive airway pressure or CPAP, is a small mask over the nose, or nose and mouth, connected to a machine that produces a flow of air to keep the airway open.) Patient struggled to achieve consistent usage due to air leak and other technical issues. He did not feel that he received adequate guidance or support as he tried to transition to CPAP.

Patient’s wife describes episodes in which he appears to be acting out his dreams. These episodes occur at least several times per month. The episodes are characterized by violent kicking and thrashing, and loud yelling in his sleep. The movements and behaviors are consistent with his dream mentation. Fortunately, no injuries have occurred to the patient or his wife.

Past medical history: A transient ischemic attack (TIA) in 2015, hypertension, and idiopathic peripheral neuropathy in right leg.

Follow-up and monitoring will focus on optimizing treatment of patient’s obstructive sleep apnea with CPAP, improving sleep continuity and quality using CBT and good sleep hygiene, controlling REM sleep behavior disorder symptoms, and minimizing risk of injury.

Medications: For the past 3 years patient has taken zolpidem (Ambien) 10 mg at bedtime, which provided some limited improvement in sleep continuity and quality. After taking gabapentin for three years he switched to 60 mg duloxetine (Cymbalta) each morning for neuropathy–associated pain and depression. He tried melatonin in doses of 10 mg and 15 mg but experienced “weird dreams” and continued “kicking dreams” during REM (rapid eye movement) sleep.

Social History: Patient is a retired newspaper and magazine writer who lives with his wife in Memphis. They experienced a sudden and devastating life trauma due to the death of their adult daughter by suicide in 2016, and this had a strongly negative impact on his sleep and mood. He drinks one serving of caffeinated beverage per day and he drinks alcohol approximately six times a week. He does not smoke. He plays squash and tennis.

Medical recommendations and clinical course: Therapeutic polysomnography (a sleep study with CPAP) was recommended. Patient was referred to a psychologist with expertise in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to incorporate CBT principles and improved sleep hygiene into his nighttime routine, with the eventual goal of tapering off Ambien.

Results: Patient wears his CPAP 5-7 hours per night consistently and reports some mild improvement in his sleep quality. After several weeks of CBT he noted gradual improvement in his ability to fall asleep and return to sleep, although he continued to struggle at times with insomnia. He was successful in tapering off Ambien.

Follow-up and monitoring will focus on optimizing treatment of patient’s obstructive sleep apnea with CPAP, improving sleep continuity and quality using CBT and good sleep hygiene, controlling REM sleep behavior disorder symptoms, and minimizing risk of injury.

The Patient’s Narrative: Sleep School

Looking back, I’m not sure if it was the article or the snoring and the kicking dreams that drove me to sleep school.

The article in The New York Times was by the healthy-living columnist, a young woman who emphasized that she was a journalist, not a medical specialist, before dispensing advice. She was a clever writer and quoted people with degrees from famous medical schools that were not likely to be on the take.

The article said men over the age of 60 should get at least eight hours of sleep a night. I was 66, got six hours on a good night and four hours on a bad one and had not slept for eight hours straight since I was in college. I got up to use the toilet at least twice a night no matter how much or little I ate or what over-the-counter sleep aids I took.

When I had decent control of my bladder and bowels, my snoring had gotten so bad that my wife started sleeping in our extra bedroom. The snore was not a gentle rustle either, but a honk followed by a whinny. And sometimes it heralded acting-out dreams with kicks and punches as I fought off alligators, unfenced dogs, and bullies.

“You fight like a girl,” my wife mocked, after being kicked in the shins a couple times. Then I whacked her across the chest one night, nearly hitting her nose, and that was the end of sleeping together.

I felt ashamed of myself and sorry for her. Not to mention the fact that I missed her warm, soft body next to me. The article said this was a common side effect of sleep deprivation.

After inhalers, dry-mouth gum, humidifiers, and a mouthpiece I got on Amazon for $40, I decided it was time to get serious. A close friend and my brother-in-law swore by their “sleep machines” — properly known as a CPAP or continuous positive airway pressure system that looked like a fighter pilot mask connected to the money-maker, a small device that produced air pressure and humidity and daily readouts.

I asked my wife if she would come back to bed. She looked at me skeptically. I took that as a no. I really missed sleeping together and spooning with her. So I made an appointment with my primary doctor who signed off, another appointment with a nurse practitioner at a sleep school who listened with little interest to my medical history and gave me a bunch of forms to fill out, and a third appointment to come in and get wired up for a sleepover.

On a Saturday night a male technician in scrubs let me in and led me down a hall to the reception room. I was the only “guest” on this night. My room was half the size of a Motel 6 room and the same quality, with a shared bathroom across the hall, cheap headboard, bedside table with a dim lamp, a double bed six feet long — I am 6’2” — and an ugly bedspread. There was a coating of dust on the window shade. The television got only one channel, TCM, which was showing Gunfight at the O.K. Corral with Kirk Douglas. On the bedside table there was a bottle of water, but no sign of the “snack” promised on the website.

The tech told me to take off my shirt and pajama bottoms, then ducked out and reappeared shortly with a cart loaded with a small computer and several rolls of cables and cords and a tube of goop. He spoke with a flat affect and did not make eye contact.

“We’ll monitor your heart rate, breathing interruptions, and snoring as well as your eye movement, EEG, REM sleep, and chin EMG. The leads attach to your chest and legs and the top of your head. The ointment makes the contacts better, but it can be a little sticky.”

Bad news. I have a hairy chest and legs and some sprouts of grey on top of my head. We tried to make small talk, but our hearts were not in it.

The tech’s eyes shifted to the floor where a large cockroach was making its way to the base of the sink. He crouched, gave it a light whack, and trapped it in a plastic mouthwash cup.

“So sorry about that. Not catch and release, but I want to show this to the building superintendent. This isn’t the first time. Remember, I am right down the hall. Checkout by the way is seven o’clock.”

I popped an Ambien 10 mg, as I had done every night for more than a year since my daughter died by suicide. The horror of thinking about her last hours was such that I could not have survived without it. I had no side effects, and usually got four hours of sleep, then got up to pee, then got two or three more hours before getting up for breakfast. The biggest problem was getting refills since Ambien is a controlled substance and I had to refill my ’scrip every 30 days in two different states where I had houses.

All the professional attention of getting your drivers’ license renewed or opening a credit card account at Walmart. Half the country over the age of 65 probably has trouble sleeping and could be classified as being in need of a CPAP.

I had my doubts whether it would work at sleep school with all those wires and goo on me, but it did. When I dozed off, Kirk Douglas and the Earps were getting the best of the Clanton gang. I woke up five hours later in the middle of a cockroach dream when I heard the voice of the tech over the intercom.

“Are you all right? You were snoring loudly and talking in your sleep, or maybe not.”

“I’m fine. What time is it?”

“Five o’clock.”

“That works for me. Come on in and get me out of here.”

Disconnecting the electrodes, as promised, removed quite a bit of hair and left globs of goop on my chest and head but I did not care. I was free and hungry and obsessed with pancakes.

After I got dressed the tech handed me some forms to fill out. A customer satisfaction survey, of course, asked “would you describe your experience as so and so.” When I got to the “how would you describe the cleanliness of the office” question and the technician question, I decided the best course was “somewhat unsatisfactory” which was below “met expectations” and “exceeded expectations.” This did not seem like the best time for score settling. On the doctor satisfaction question, though, I wanted to write in “HAVE NOT SEEN ONE, YOU PRICKS!” but settled for “does not apply” instead.

Half an hour later I was home eating blueberry pancakes.

The written report arrived in the mail a week later.

“Congratulations!” it opened, in the manner of a notice from Publishers Clearing House.

“You have completed the diagnostic portion of the study and have been scheduled for a second study to determine your CPAP titration and the proper pressure to treat your obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). After your second study we will order a CPAP machine from a Durable Medical Equipment (DME) company. If you have any questions, please call your doctor’s office at this number.”

Which is exactly what I did, to try to find out how much I was going to be charged for this little adventure. It took half an hour to get through the phone tree to a live person.

“Well, Medicare will cover everything but the cost of the room, which is $80 a night.”

“Yes, that’s fine, but what is the actual cost of, like, the whole deal?”

Ever the investigative reporter, and a cheapskate to boot.

“The total full cost of the first night is $8,000 and the second night is $7,500. But the charge to you is only $80 a night because you have Medicare.”

I wrote it down, said thanks, and hung up, full of unspoken fury: a Medicare scam, bill 15 thousand, collect nine thousand, run the paperwork through the back office, get a sleep doctor to sign it. Bingo. All the professional attention of getting your drivers’ license renewed or opening a credit card account at Walmart. Half the country over the age of 65 probably has trouble sleeping and could be classified as being in need of a CPAP.

Much as I wanted to dig deeper, there was still the matter of my snoring, which was getting so bad I woke myself up most nights, alone in the bed. So, two weeks later I went back to sleep school. This time the tech was all business. I got a quick demonstration of how to put on the mask covering my nose and mouth (for “mouth breathers”), attach the headgear to the six-foot hose, some gibberish about the computer readouts and adjustments, and a bedroom minus roaches.

To get the gear, I would have to make an appointment at another office near the airport. The helpful staff answered my questions as I took notes, but it was a lot to digest and experience proved the best teacher. I chose not to enroll in the auto-resupply program, which meant I was on my own when it came time to get replacement masks, hoses. and filters. This was a hassle, but an instructive one. A filter the size of a postage stamp, for example, can cost five bucks; a soft plastic cushion for the face mask is $14 on Amazon, and anywhere from $30 to $80 from a certified provider — unless you have met your Medicare deductible.

After a couple of years of this, I switched doctors (to be clear, I never actually saw a doctor until I “switched”). Dr. Wise and I hit it off immediately. He listened, he laughed, he answered emails so readily that I feared I was cheating him out of his fee. He helped me through the paperwork — a big source of stress for me — and warned me to wean myself off Ambien carefully, not suddenly, lest I relapse to even worse insomnia. Best of all, he suggested I see a therapist who put me on a “sleep diet.” I charted my bedtime and wake-up time each day, limited myself to one 15-minute nap, and stayed in bed no longer than eight hours.

My “sleep efficiency” improved from 60-70 percent (five hours of sleep in eight hours) to 80 percent. Four years after my daughter’s suicide I stopped taking Ambien. In the seven months since then, I have taken only two pills.

I cannot say all is well. I still fight the CPAP mask, it inhibits kissing and affection, and it looks ridiculous. It stops my snoring. More oxygen is better than less. But it is not the miracle machine proponents say it is, at least not for me. I have a new acronym — RBD, or REM sleep behavior disorder. In other words I still kick and punch sometimes. But my wife has stuck with me, and I recently turned 72 with guarded hope.

The Physician’s Narrative: A Desire to Fix Things

My first impression as I met John was that, for several good reasons, he was frustrated at how little help he had received for his sleep difficulties. Like many of my patients in sleep clinic, he was tired of being tired.

The depth of his frustration was so significant and his well-founded mistrust of people in healthcare was so intense that my first priority was to just listen and take in his story. John’s eyes flashed as he told his story in colorful fashion. I recall his dry humor and his ability to tell his story in vivid detail, with “sidebar” commentary leaving no doubt how he felt. He was angry and he wondered aloud if “this whole sleep thing is a scam.” He felt taken advantage of, and even though I did not cause the problems, I felt embarrassed that some in the field of sleep medicine had missed the mark so badly.

Not long after we began working together, I asked John if he felt that writing about his experiences would be something he would consider. Within a few days, I received John’s written story in the mail and what you read above is essentially what he shared with me. Reading John’s essay left me with two main thoughts: 1) MAN, THIS GUY CAN WRITE, and 2) when John writes about his sleep, he is writing in a highly personal and authentic way about his life and his perspectives on life.

In keeping with the idea that “breathing comes first,” we forged a working relationship focused initially on finding solutions to John’s technical difficulties with CPAP. This allowed some trust to develop and we moved into the more challenging task of addressing John’s chronic insomnia and his REM sleep behavior disorder (dream enactment).

John’s sleep story continues, and like all stories that involve the human condition, sometimes things are better and other times they are not. At times, I still wish I could “fix” all aspects of John’s sleep but that is not how it works.

The central role that the death of John’s daughter by suicide played in his sleep problems was a clear reminder of how personal sleep is for each of us. Everyone has a “sleep story,” and often many sleep stories. How we sleep affects how we feel and function during the day, and what happens during the day affects how we sleep at night. For John, this situation has been a horrible cycle of grief, mourning, and depression punctuated by really bad sleep, followed by another painful day, and so on. I have genuine admiration for John as he faces each day followed by each night of sleep, or lack thereof.

I cannot begin to understand how John feels and how he experiences this cycle; formal medical training does not prepare physicians to fully understand. Physicians-in-training hear lectures on topics like “Delivering Bad News” or “How to Tell a Patient He Has Cancer.” I had the distinct impression that for John, every day and every night were relivings of his experience of receiving bad news. His sleep problems are a visible and frustrating sign of the invisible pain and suffering he has endured.

Like lots of physicians, I get up every day with a desire to fix things, to make life better for my patients. There is real value in working to fix things. The problem is that I am never able to “fix” the painful and traumatic experiences that others live with.

It has taken many years for me to learn to appreciate the difference between fixing things and walking with others through their pain and suffering. Only then, and in partnership with the patient, am I able to help create a way to lessen the burden of pain and suffering. In my case as a sleep specialist, this means a pathway to improved sleep health and hopefully better quality of life.

John’s sleep story continues, and like all stories that involve the human condition, sometimes things are better and other times they are not. At times, I still wish I could “fix” all aspects of John’s sleep but that is not how it works.

John Branston lives in Memphis and wrote for wire services, newspapers, and magazines (including this one) for 40 years. He is the author of What Katy Did and Rowdy Memphis. He can be reached at johnbranston71@gmail.com

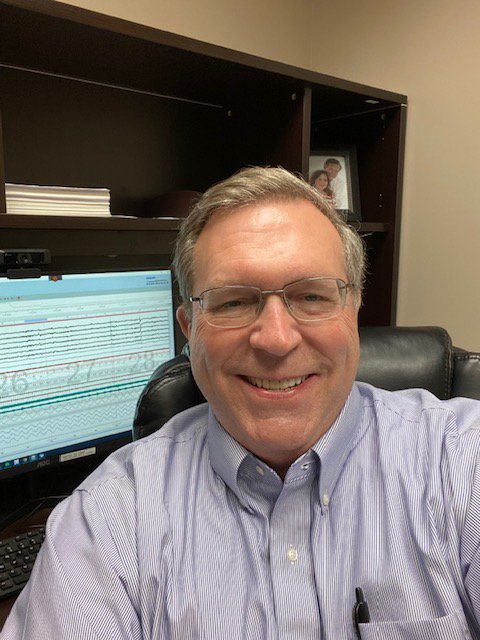

Merrill S. Wise, MD, is a neurologist and sleep medicine specialist engaged in the full-time practice of sleep medicine in Memphis. He lives with his wife on Mud Island and can be reached at merrillwise1@gmail.com