Continuing the theme from the last post, we cannot solve our region’s child poverty rate – the highest of any MSA in the country – unless we are address the need for better paying jobs for parents.

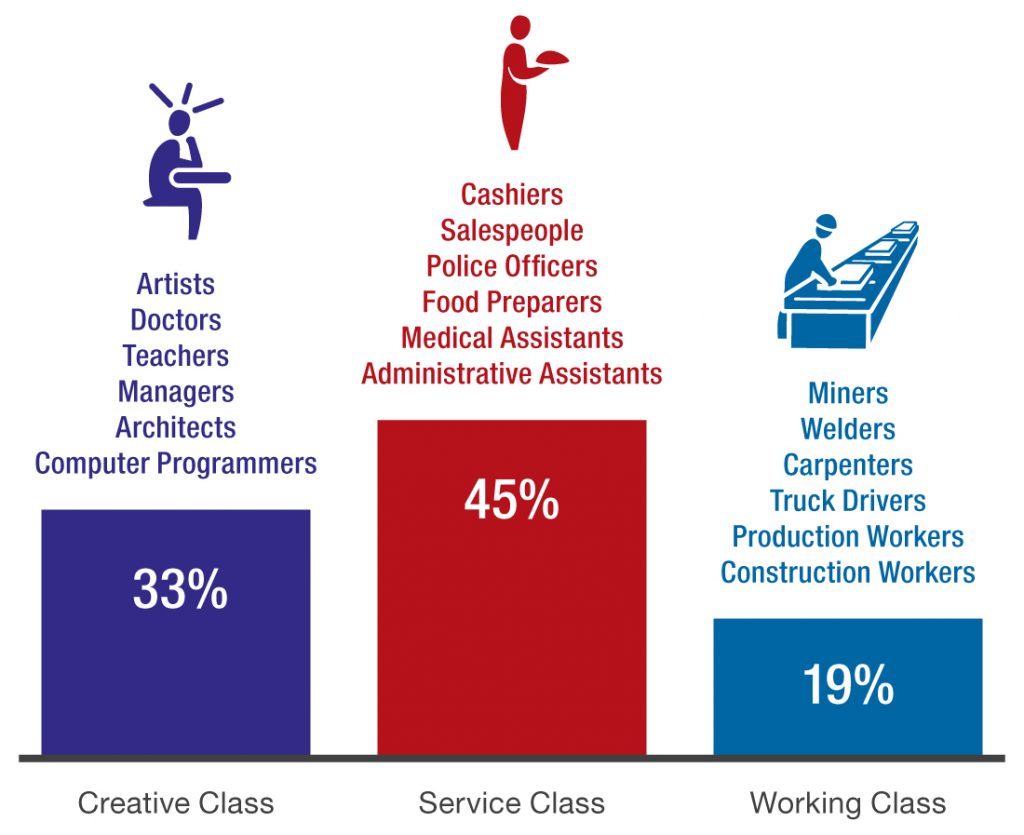

With its reliance on service class jobs, Memphis must come to grips with the idea that opportunity is not defined by more and more low-wage jobs that do not pay enough to cover typical expenses for our workers and their families.

Annual salaries for service workers in Shelby County average between $18,540 and $23,880. That means the jobs pay poverty wages (poverty is defined as less than $24,250 for a family of four) and they stand in stark contrast to Memphis’ already low median household income for African Americans – $35,542.

One more fact: the typical annual expenses for two adults with two children are $48,708.

Tough Trend Line

That said, most service class jobs are disproportionately handled by women, which means that in a city with one of the highest rates of female-headed households in the U.S., average service class salaries are especially damaging in the lives of so many Memphis children.

The lethargic trend line for service class job salaries is part and parcel of the country’s rising inequality and the decline of the middle class. Unquestionably, the same impact is taking place in the Memphis region.

And yet, in discussions about creating good jobs, these service workers are routinely ignored. The talk is about breathing life into manufacturing and bringing jobs back from overseas, about creating tech jobs, and about the creative economy, but it rarely turns to ways to improve salaries for service workers.

With the disproportionate number of service jobs here, closing the income gap could be one of the most important economic development priorities we should have. Meanwhile, companies need to provide devise opportunities for career advancement and encourage innovation.

Empowered

We think about a visit with Craig Marshall when he was general manager of the Hampton Inn and Suites in downtown Memphis. At the time, it was the highest rated Hampton Inn in the country, and a visit indicated why.

The line workers had been given power and pride and reasons to foresee advancement. A former housekeeper climbed to manage the front desk and every worker had the power to waive a guest’s bill if a complaint was lodged. It created a sense of camaraderie that translated into customer service and then into profits. In conversations with the workers, it was clear that they felt appreciated and empowered as an important part of the hotel team.

When employees – whether they work for Costco or Four Seasons – are given the power to make decisions and have paths to internal promotion, research indicates there is more shop floor innovation, better customer service, and higher productivity.

Memphis has tens of thousands of men and women working in the tourism industry, which is notorious for its low wages. At a time when our tourism industry is reaching a record level of direct visitor expenditures – $3.2 billion, it would make sense for it to lead the campaign to consider how service workers can be paid enough to not qualify for food stamps.

Memphis ranks #44 among the 51 largest MSAs for highest average service class wage.

Net Loss

Today, service class workers are about half of the entire U.S. labor force, and the jobs are just as low-paying, low skill, and drudgery as they were 25 years ago.

It has been especially harsh for those without a high school degree. From 1990 to 2013, the median earnings for working men between 30 to 45 years old without a high school degree fell 20% when adjusted for inflation and women in the same category had their median earnings fall 13%.

In other words, not have we been drifting into two Americas but the people who were already not earning much working as housekeepers, groundskeeping, food service and cleaning were put in a squeeze that made the middle class became a fleeting dream.

It is complicated by a fact of life for the United States and for the Memphis region: the jobs being created really do pay less than the jobs being lost.

Quit Digging

In this regard, since 1980, we have been digging a hole deeper and deeper with our emphasis on low-wage, low-skill jobs and with the explosion of transportation, distribution, and logistics jobs. Upgrading these service class jobs has to be key to any plan to create good jobs and build the middle class.

After all, blue collar manufacturing jobs were once considered low wage, low skill work. In that industry, it was the right to organize into unions that changed things. Later, Japanese manufacturing models based on the concept of paying workers well but keeping a lean management were integrated into American factories.

Research shows that companies like Costco and Whole Foods that pay service class workers more and offer more job security and opportunities for promotion have proven successful in getting more out of their workforce, reducing turnover, improving productivity, and becoming more profitable.

It Takes A Plan

We say all this to make the point that it’s time for our economic development leaders, elected officials, and labor groups to consider how to upgrade these service class jobs. It could begin with increasing the floor for minimum salaries for companies seeking PILOTs and campaigning to increase the minimum wage of $7.25 an hour. For example, if the minimum wage in Memphis were to be the equivalent of 50% of the median wage, it should be $7.94.

Because public and civic policy was central to creating the disproportionate number of service jobs in Memphis, such a discussion should begin with analysis that begins at the same place.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.

It will take many decades to move away from the current service worker mix. The dependency on warehouse and retail low wage jobs is killing this city. In the meantime Memphis will languish and continue to fall behind practically every American city.

Ongoing local High School grade scandals creates an environment of low skilled workers.

I’m all for increasing the current wage level up to a living wage standard, but the sad fact remains that the minimum wage is beyond the skill level of a lot of the people who are currently being paid that wage. The level of service being provided even at the minimum wage level is so poor that they don’t deserve what they’re getting, much less a higher wage.

Poor city. Uneducated population. Not going to improve.