In our first post, we began our list of 10 things that made us who we are today.

In that post, we listed:

* Shelby County Encourages Middle Income Families to Leave Memphis

* No Commitment to Planning

* Ignoring the Need for Equity

In the second post, we added two more:

* Lock ‘Em Up Law Enforcement

* County Government Delivers Urban Services

In this post, we add:

* Failing to Create a Real Memphis MPO

* Chasing Population Through Aggressive Annexation

First for today’s post is Failing to Create a Real Memphis MPO.

The results of a lack of commitment to planning in Memphis and Shelby County is seen all around us – a planning department that has about nine planners while comparable cities have three to four times that number, legislative disregard for the planning function, subjective opinions substituted for professional planning principles, a process overly influenced (if not driven) by development interests, an overriding lack of context for making smart decisions about neighborhoods and sustainability, and the absence of an aspirational planning vision of what the future can be for our community.

But few agencies charged with planning have proven to be as much of a dismal failure as the Memphis Urban Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO). It is hard to think of a public agency that has had a more devastatingly negative impact on the community it was created to serve. There are similar organizations all over the United States, but our MPO has been recognized for more than a decade as being one of the most inequitable, least representative of them all, leading to a suburban bent to its decisions and more and more highways fueling sprawl that undercuts the strength of Memphis.

But more than that, the MPO has set an agenda with a marked anti-urban attitude (or at the least, an attitude of benign neglect) when it comes to Memphis, particularly regarding the need to balance roadbuilding with support for public transit.

Chuck Marohn of Strong Towns, brought to Memphis by the Mayor’s Innovation Delivery Team, has said it well: “The MPO is the single largest obstacle to positive change and reform that Memphis has to deal with. This is ironic because it is an organization that works on broad consensus, does not project much power and authority and seems bureaucratically averse to controversy. The MPO holds the purse strings for billions of dollars, however, and that money that has been and is continuing to be used to reshape the Memphis region in a way that is destroying its long term financial viability. This system needs immediate reform.

“The first thing to note about the (Memphis) MPO is that it is not really a planning organization. Community planning and regional planning involves much more than simply allocating transportation dollars. Transportation has an enormous impact on land use, but land use also dramatically impacts demands and preferences for transportation. To be completely blind to one half of that equation, or worse, to believe that government transportation spending is simply a response to demands of the free market is dangerous, particularly when dollars allocated by the MPO overwhelm any other capital spending or local economic development initiatives.

“Contrary to the current focus of the MPO, the Memphis region does not have a congestion problem. Congestion is a symptom of poor land use practices that give people no option but to utilize the hierarchical road network for every trip. Since money allocated to transportation projects through the MPO go predominantly to fighting congestion, it reinforces the existing hierarchical road network. Ultimately, that spending simply increases the congestion problem while moving it from one place to another…

“The MPO needs to be reformed to give Memphis a greater voice. It also needs to either significantly diminish its role so that it is strictly in service of local planning and economic development initiatives or it needs to become more active and collaborative in those efforts. The priorities of the MPO – fighting congestion, expanding capacity and securing the maximum level of funding need to be subordinated to the priorities of (1) maintenance of critical system components, (2) a focus on high return investments and (3) increasing the value and producing of existing Memphis neighborhoods.”

Chasing Population Through Aggressive Annexation

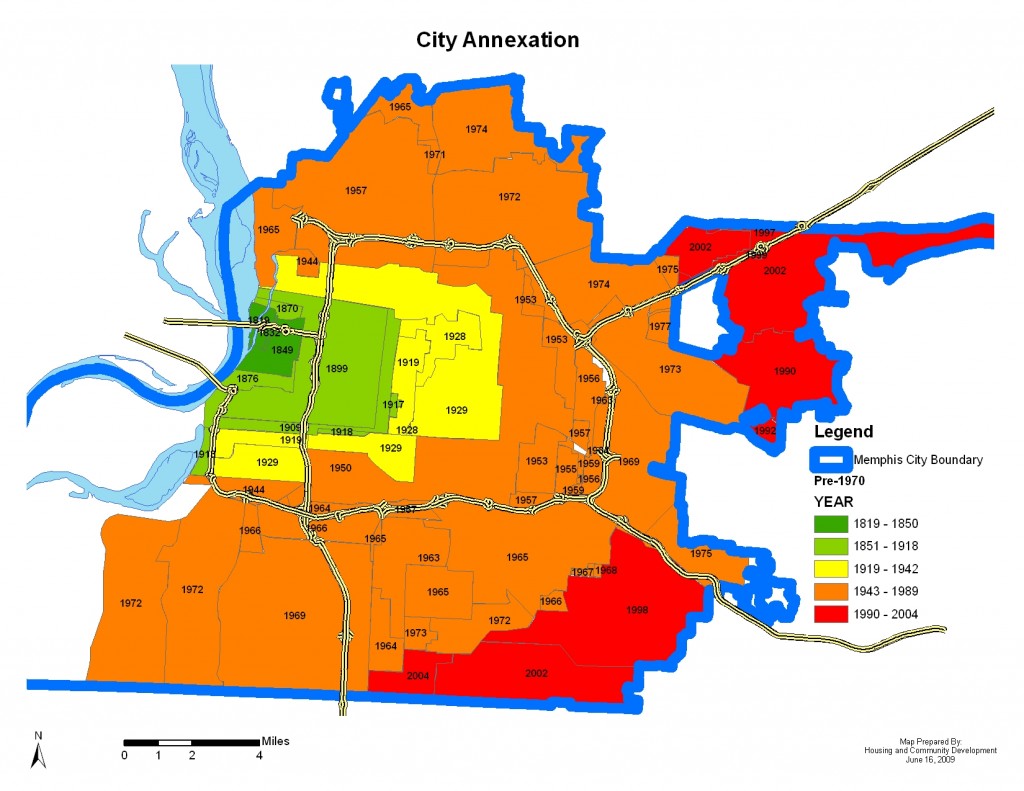

We were arguably the first people to point out that Memphis is a shrinking city. The city’s annexation policy masked that fact for decades. It kept the city’s population at roughly the same level, but it was done by taking in more people rather than by attracting more people to live within the borders of Memphis. Unfortunately, the focus on annexation also masked the fact that in annexing new territory, Memphis was in fact disinvesting in neighborhoods whose decline was accelerated and whose infrastructure was already paid for.

As we have pointed out often: today’s population within the 1970 city limits of Memphis is roughly 30% less than it was in 1970. In the meantime, Memphis has cut its density in half as it annexed about 150 square miles of additional land.

The lure was new property taxes for a city strapped by one of the three most regressive state tax structures in the United States. Put simply, the less you make in Memphis, the more you pay as a percentage of your income, and as the city hollowed out and middle income families moved out of the city limits, there may have seemed to be little alternative but to chase new revenues wherever they could be found.

And yet, because the price for that new revenue was more responsibility over a larger area and no more to spend on core neighborhoods that are the heart of Memphis, the entire transaction may have been built on a false economy. The study required to determine if annexation was smart for Memphis was simply math that showed that new revenues were more than the cost of services to the new area. The analysis failed to determine the cost paid by the neighborhoods left behind and the increases in the unit cost of services increased because it costs more to deliver services in neighborhoods where half of the houses are vacant and density has been cut in half.

But back to the main point: Memphis is a shrinking city, so it’s no surprise that we’re showing many of the symptoms that perplex other cities fighting similar realities – the hollowing out of middle class families, more than 40,000 abandoned houses, loss of retail and job centers to suburban areas, declining city revenues for services other than police protection, lethargic economic growth, and more.

These would be troubling trend lines in the best of times, but when Memphis was upended by the Great Recession, it produced challenges of crisis proportions. And without a plan and with too much land to deliver services to, it led to ad hoc strategies that were pursued in hopes that at least some of them would work. But because there was not a firm foundation built in an orderly, dependable growth plan, these were hit and miss.

In a sense, Memphis’s unwavering focus on more and more annexation led it to miss the opportunity that could have resulted from the Tennessee Growth Policy Act, also called Chapter 1101 of 1998. The law called for every county in Tennessee to develop a comprehensive growth policy plan for the next 20 years.

While other counties were coming together – cities’ governments, boards of education, utilities, and county governments – to reach agreement on drawing urban growth boundaries, planned growth areas and rural areas, Memphis was fixated on short-circuiting the process in order to accept the annexation reserve agreements between Memphis and the smaller towns as a de facto growth plan.

Of course the annexation reserve agreements were about the farthest thing from a real growth plan, because most of the county was classified for urban growth and except for the Shelby Forest area and the northeast corner of Shelby County, there were no rural areas. It was a rich opportunity to think differently about the future of Memphis, the municipalities, and Shelby County, but expediency won out over sound planning (as it so often does).

The current City Council – which deserves considerable credit for squarely attacking the double taxation paid by Memphians for many city-county services and pushing services that should rightfully be funded by Shelby County Government over to it – has indicated an interest in ending the “annexation first, ask questions later” approach that has defined city government.

Instead, some Council members have talked about whether deannexation could be a way to improve services, bring more order to city budgets, and put the focus where it belongs – on the city’s core. (Unfortunately, they did not abandon the long-standing Windyke annexation that could have sent a strong message about a new day dawning, but racial politics kept that from happening.)

Despite the fact that Memphis City Council has no real appetite for further annexation or plans to pursue it, the Tennessee Legislature – as it is prone to do – stepped in to limit the options of the state’s urban areas generally and Memphis specifically. The Legislature passed a law that requires cities’ annexations to be approved by a majority of landowners in the area to be annexed.

It clearly brings annexations in urban areas like ours to a standstill, and maybe in time, that will turn out to be a good thing. Without the placebo effect of annexation, perhaps we’ll turn to diagnosing and solving the issues that limit our opportunities to thrive and succeed.

It’s impossible for us to laud state legislators’ willingness to interfere in so many ways in the lives of its cities, but with a new reality for the foreseeable future, Memphis can turn its attention – and demand that Shelby County Government helps as a partner – to strengthening Memphis neighborhoods, attracting people with choices to move back inside the city limits, providing choices for people that have none, and finding a way to be recognized as America’s newest “turnaround city” in the years to come.

Next Post: The Last Three in Our Top 10 List

I will add that the past annexation/pro-sprawl policies not only contributed to hollowing out the middle class but also to less families entering it.

One of the fastest ways to enter the middle class is through gained equity in one’s home. However in Memphis, the constant flooding of new homes onto the market – with no corresponding population growth to justify it – depressed the values of older properties in the urban core.

There are/were many African-Americans home owners in Memphis, but they did not see the home equity gains as in cities like Atlanta or Washington. Blacks in those cities were able to take equity out of current homes and even buy rental properties. Meanwhile blacks in Memphis saw stagnant or even decreases in their home values.

I personally know many poor people in Memphis that actually own homes. They are no less talented than their counterparts in cities like Washington or Atlanta. If their property values had escalated, their lives would have changed for the better. The city would be better. However the policies just never allowed for that.

In short, aggressive annexation has contributed to people remaining in poverty.

WCN-

Great thoughts! While a depressed housing market- the roots of which and the impact it has on the city and region as a whole has been discussed in great length- I do not think I have read or given much personal thought to the impact it has had at the individual level where equity and financial stability is concerned. It is a very important aspect of city building that does not receive the attention it should as related to the overall health of the community.

Once again, great contribution!

Memphis 2040 plan?

or was it the Memphis 2050 plan??

tying land use, sustainability and MPO planning together with social media

singing a chorus of Kumbyyah in the background.

it was in the ‘paper’ at the time 🙂

A disturbing CA article indicates that Mayor Luttrell has a separate legislative agenda from AC Wharton to eliminate Memphis’ powers to zone and regulate subdivisions outside of its corporate boundaries. (CA 12/2/14, “Wharton Luttrell renew requests of general assembly…….” Thus the one power Memphis has to control its destiny could be eliminated. This looks like the developers fear a Memphis City Council that will look harder at sprawl than before recession due to fiscal problems caused in part by sprawl.