Photo: Porter-Leath and University of Memphis Early Childhood Academy in Orange Mound

By Rob Hughes

In a city of reinvention like Memphis, deep, sustained investments rarely survive more than a generation. But Porter‑Leath has defied that pattern. As the organization marks 175 years of service to children and families, it offers a vivid case study in what “upstream investment” looks like when anchored in community, adaptation, and intergenerational impact.

Origins: Meeting urgent need in an early city

Porter‑Leath traces its roots to 1850, when a group of Memphis citizens—including widow Sarah Leath—came together to form the Protestant Widows’ and Orphans’ Asylum, offering food, shelter, and care to vulnerable women and children who otherwise had nowhere to turn.

Over time, the institution’s name shifted to Leath Orphan Asylum, and later, to Porter‑Leath to include contributions made by Dr. David T. Porter and his family. From its earliest days, Porter‑Leath was an upstream investment: a local-scale institution that committed not just to reacting to crisis, but to creating infrastructure of support for those with few safety nets. Over decades, this foundational capacity would prove critical.

Surviving crises, building resilience

As Memphis and Shelby County evolved, Porter‑Leath repeatedly proved its resilience. During the Civil War, the institution maintained operations and in the 1870s, many children were orphaned, driving urgent demand for services as a result of the yellow fever epidemic. The Independent Order of Odd Fellows contributed funds for expansion in 1876 in response.

Through the turn of the 20th century, upgrades like plumbing, electric lighting, and structural expansions kept the campus viable. In 1904, a gift from Dr. David T. Porter cemented the institution’s future, and the Porter name formally entered.

In subsequent decades, Porter‑Leath navigated the Great Depression, wartime resource constraints, shifting philanthropic norms, and changing social welfare policies. These periods tested the organization’s model, yet it continued expanding capacity and services, often by combining with complementary institutions and adapting to serve the needs of the day’s children and families.

By the mid-20th century, as institutional orphanages declined in relevance thanks to rising social safety net policies, foster care systems, and social welfare reforms, Porter‑Leath pivoted. It recognized that pure orphanage care was no longer sufficient or aligned with contemporary child welfare. Those shifts illustrate what upstream investment must accompany: not rigid continuity, but responsiveness and reinvention.

Evolving mission: from care to prevention and enrichment

While Porter‑Leath started as a reactionary institution for those already in crisis, its modern incarnation embraces upstream prevention and early intervention. Over the past few decades, the organization has built capacity in early childhood education, family support, teacher development, and community collaboration, becoming the leader in helping children and families succeed.

● As State systems began to come online in the 1950s and 1960s, the orphanage model evolved to group homes and foster care. Porter-Leath immediately began providing both, with foster care continuing under the Connections umbrella of services.

● The 1970s offered Porter-Leath the opportunity to host the Foster Grandparent Program and provide opportunities for seniors to reinvest in their communities through volunteer service. Porter-Leath added other components, such as AmeriCorps, over time and now provides almost 100,000 hours of service per year through its Generations focus area.

● In the 1990s, the Home Instruction Program for Preschool Youngsters (HIPPY) arrived in Memphis via Porter‑Leath, helping parents become their children’s first teachers. Around the same time, it adopted the Maternal/Infant Health Outreach Worker (MIHOW) curriculum, expanding to serve pregnant women and children birth-to-five. This segment has evolved into the agency’s Cornerstone program and uses the evidence-based Parents as Teachers curriculum to advance healthy birth outcomes and parenting best practices. Over 86% of pregnant women delivered a healthy birthweight infant last year.

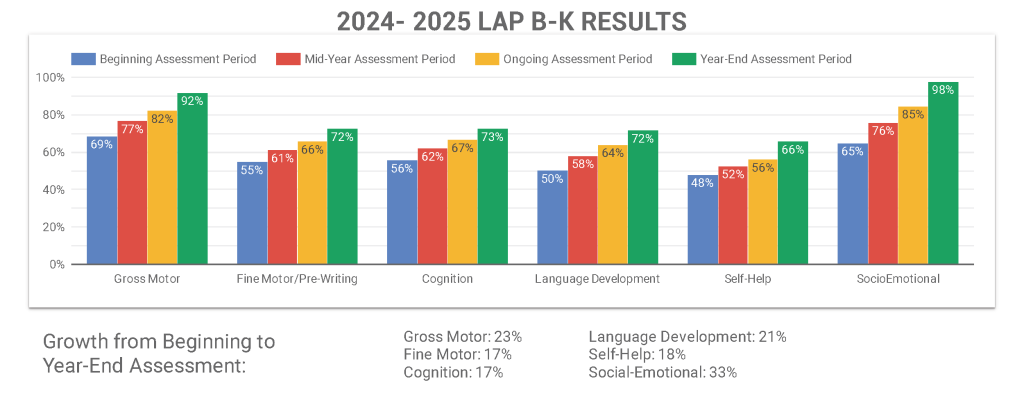

● In 1998 the foundation of Preschool began as Porter‑Leath became the first Early Head Start grantee in Shelby County, serving children from infancy to 3 years, including center-based and home-based components. Additional grant funding was secured to expand the program’s reach, most recently in 2024 with Porter-Leath awarded though a highly competitive national competition. In addition, this work earned Porter-Leath the Program of Excellence distinction from the National Head Start Association, an accolade bestowed to only 13 grantees out of 1600+ nationally. Porter-Leath has sustained top outcomes for children each year, with children showing at least a 17 percentage point gain in each domain measured last year:

● In the 2010s, a bold capital campaign created multiple early childhood academies across Memphis, including a partnership with the University of Memphis. Porter-Leath injected over $40M into early childhood infrastructure to provide top quality learning environments.

● Recent years have also seen the rise of the Teacher Excellence Program to provide practice-based coaching and professional development for early educators, the addition of Books from Birth through a 2017 merger to align Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library’s literacy work with other early childhood programming, and the creation of NEXT Memphis, a support and technical assistance incubator for high‑quality child care providers. Porter-Leath is also home to the Early Success Coalition, a network of home visitation providers and early childhood practitioners to promote early childhood development.

Through this trajectory, Porter‑Leath has shifted its locus of impact earlier in children’s lives and closer to the roots of inequity, not waiting until problems have grown severe.

Measurable scale, catalytic transitions

A key feature of long-term upstream investment is scale—not just reaching more people, but shifting the ecosystem. Porter‑Leath today serves more than 40,000 children and families each year across multiple program areas. In 2025, Porter-Leath reported numerous milestone metrics for the year:

● More than 400,000 books mailed to children in Shelby County via Books from Birth

● 640 families served through Early Head Start and 594 children served through Preschool

● Over 3,000 hours invested in practice-based coaching through the Teacher Excellence Program

● Over 95,000 hours served by Foster Grandparents and AmeriCorps members in Generations

● The Early Success Coalition supported 78 partner home visitation programs and expanded the Doula Network

In 2025, Porter‑Leath’s selection as the Head Start grantee for Shelby County illustrates Porter-Leath’s prowess: the organization is not merely a nonprofit among many—it is becoming a backbone of early childhood infrastructure in the region.

Sustained outcomes and continued growth do not come without difficult decisions elsewhere. In a sign of Porter-Leath’s organizational maturity and commitment to making best use of available assets, the agency has made two more recent changes in a sign of major landscape shifts. In 2023, Porter-Leath sold a portion of its Manassas campus to Memphis and Shelby County Community Development Association (CRA) as the agency had outgrown the historic buildings but wanted to find a buyer who shared the agency’s commitment to preserving these edifices.

Porter-Leath retained two buildings on the campus: the Early Head Start Center and Sarah’s Place. The latter was used as a congregate care facility for teens pending foster home placement within the agency’s Connections focus area, but was closed in 2024 as shifts in foster care proved that youth were better served outside of the group home model.

What “upstream investment” means in the Porter‑Leath lens In business and development jargon, “upstream” often refers to investing early.

In the public health field, upstream investments target social determinants before problems become crises.

Porter‑Leath’s 175-year arc is a testament to how an institution internalizes that logic over time—shifting from downstream crisis response for orphans, to maturing toward prevention, enrichment, and community capacity‑building.

Here are a few lessons observed in that arc:

1. Institutional endurance matters

A 175-year organization can make multi-generational bets. It weathers downturns, reorganizations, and policy shifts. That stability creates trust and leverage with partners, funders, and public systems.

2. Adaptive reorientation is essential

Rather than cling to the original orphanage model, Porter‑Leath evolved programs, merged with complementary agencies, and refocused on early childhood and family support as societal needs changed.

3. Infrastructure over episodic grants

Over time, Porter‑Leath has built physical campuses, created systemic and sustainable models (Teacher Excellence Program and NEXT Memphis), partnership-led collaboratives (with First 8 Memphis and over 40 partners to provide community-led service) and embraced evidence-based curricula (like home visitation, Early Head Start, and Head Start). These aren’t stop-gap services—they constitute ongoing platforms.

4. Catalytic system shifts

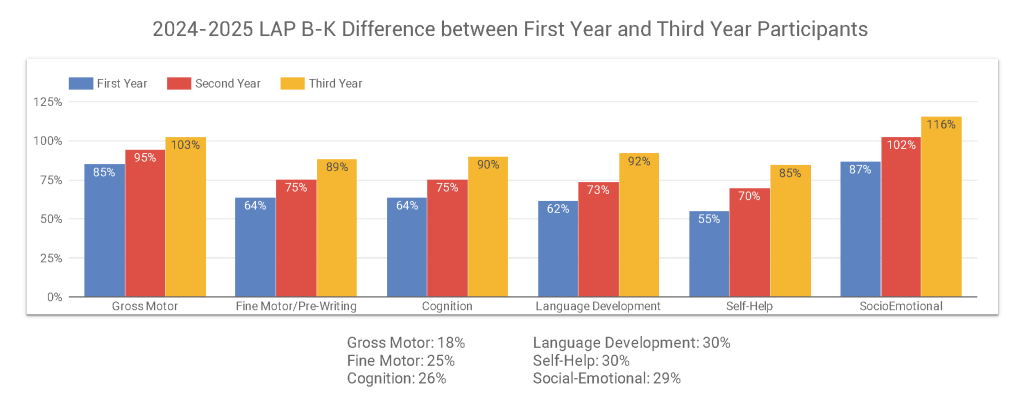

By serving over 4500 children each day through Early Head Start, Head Start, Pre-K, and tuition-based Preschool, Porter-Leath has created a universal access Preschool built on quality outcomes for children. In addition, Porter‑Leath is not just serving more children—it’s shaping how public early education is delivered locally. That is a systems-level influence of upstream investment. Showcasing the organization’s outcomes for children who participated in all three years of Early Head Start, Porter-Leath has a major opportunity to amplify its early childhood impact for thousands of children each year.

5. Balancing legacy with forward momentum

The sale of historic campus buildings shows that upstream investment is not sentimentalism. It requires hard decisions about which assets advance the mission and how to best steward current and future resources.

6. Deep place-based grounding

Because Porter‑Leath has always been anchored in Memphis, its institutional history is intertwined with local resilience—yellow fever, pandemics, civil war, urban decline, education reform, neighborhood shifts. That local rootedness gives its investment authenticity and credibility.

Conclusion

The story of Porter‑Leath is not merely a chronicle—it is evidence of what decades and centuries‑long upstream investment looks like in a city. It shows that to produce durable change, you don’t just respond to crisis—you build the architecture of prevention, enrichment, and adaptation over multiple generations.

In Memphis, where cycles of challenge and reinvention are often compressed in short time spans, Porter‑Leath stands as a testament: upstream investments aren’t glamorous, but they shape who and what a city becomes for decades. As Memphis enters new eras of growth and equity, Porter‑Leath’s 175-year legacy offers a blueprint: invest early, invest deeply, adapt, and maintain institutional fidelity to mission over time.

**

Rob Hughes is vice-president of development at Porter-Leath.