By John Branston

It was a sad kickoff to music month in Memphis when Beale Street neighbor Clayborn Temple burned to the ground, leaving a scene that looked like bombed-out German cities after World War II.

Clayborn Temple, like nearby St. Patrick Catholic Church and Beale Street Baptist Church, is such a big part of our history culture, and architecture. As is FedEx Forum, a more recent chapter in the story. On a walkabout with out-of-towners, you can see them all in a few minutes or a few hours and see The Peabody and Orpheum too.

When I moved to Memphis in the Pleistocene era of journalism in 1982, one of the first people I interviewed was Rufus Thomas, who graciously led me on a tour of Beale Street as it was under renovation after years of neglect and decay. His conversation was a series of amusing anecdotes about blues Greats, Near Greats, and Wannabes spanning half a century. He was not happy that pop singer Lou Rawls from Chicago was chosen instead of him as the face and voice of the new Beale.

“Wouldn’t you want someone who was here and lived the history?” he said.

Then as now, Beale Street was as much about marketing, egos, enablers, and elbows as history. The musical notes embedded in its sidewalks ought to be $ signs in more than a few cases. Well, there is something to be said for that, and maybe a lot. W. C. Handy died in 1958, and Beale wasn’t going to make it selling junk at A. Schwab’s or suits at Lansky’s. Silky Sullivan successfully migrated from Overton Square and outlasted joints named for Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis. Blues City Cafe started in 1991 as Doe’s Eat Place and morphed into something with real legs. The Rum Boogie Cafe has been a cornerstone since 1985 and resists, as does B.B. King’s Blues Club, the temptation to be more like Lower Broadway and its bachelorette parties in Nashville.

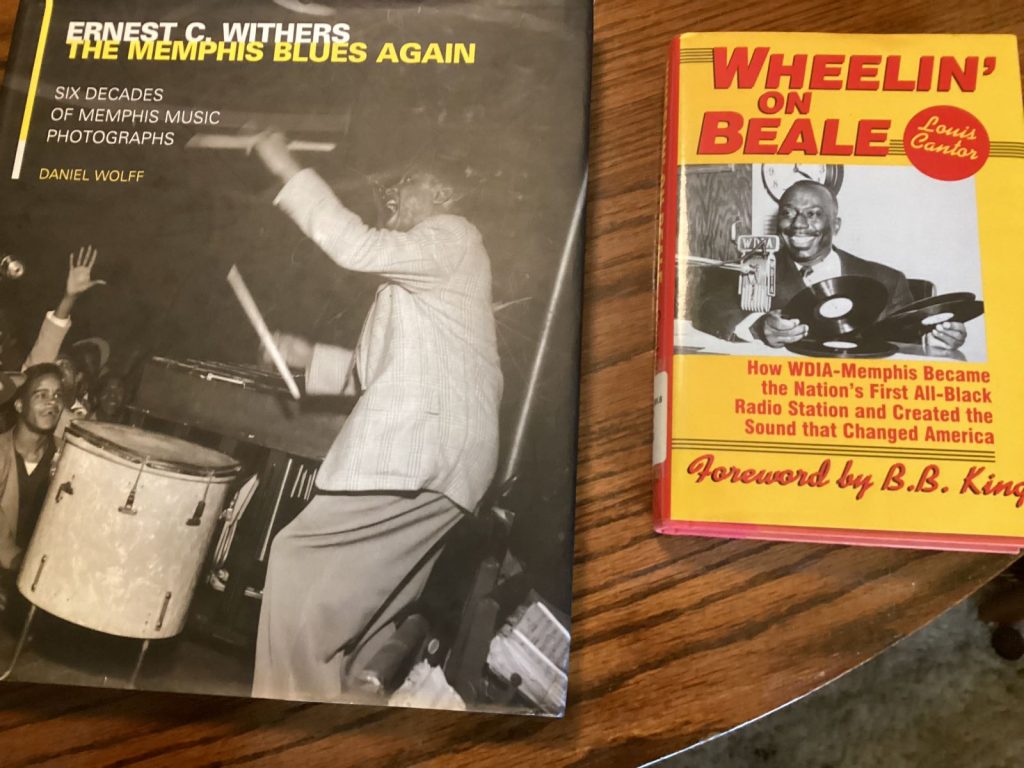

Thomas was shrewd, funny (“Do the Funky Chicken” was his big hit), and – like any good comic – did not mind playing the fool or being politically incorrect. The ubiquitous Beale Street photographer Ernest Withers shot him playing “Chief Rocking Horse” in Indian headgear spouting lines like “me shoot many buffalo” with his buddy Nat D. Williams.

Williams was the star DJ at WDIA, the first all-Black radio station. Thomas called him “the Jackie Robinson of radio” (Robinson broke the color barrier in baseball in 1947; Williams went on the air in 1948.) Williams taught history and social studies at BTW High School and wrote a newspaper column as a side hustle. He made his own rendition of Handy’s line “if Beale Street could talk, married men would pick up their beds and walk.” He also came up with “dollar-gration” for integration in Memphis. In his excellent book Wheelin’ on Beale, author Louis Cantor quotes Williams saying that although he was the first Black person the owner of WDIA had ever met “he hired me because I looked so much like the rest of ’em.”

Nicknames were one of the secrets of success to old Beale Street. A blues singer named McKinley Morganfield, Chester Burnett or Gertrude Pridgett had as much chance of making it as “Muddy” Beethoven, “Howlin’ Wolf” Mozart or “ Big Mama” Callas. A dose of attitude didn’t hurt either. When Joni Mitchell visited Memphis in 1976, she wrote the song “Furry Sings the Blues” in which Furry Lewis wags a finger at a crowd and growls “I don’t like you.”And he didn’t like her or the song. This was long before the days when music stars and college athletes could collect millions of dollars in Name Image and Likeness money. In my rookie year in Memphis, I contacted another old bluesman for a comment and he refused – rightly – to talk to me unless I paid him.

Elvis (a frequent visitor to Beale Street) made his Memphis debut in 1956 on WDIA’s Goodwill Revue at the Ellis Auditorium before a mostly-Black crowd of 9,000. “How come cullud (sic) girls would take on so over a Memphis white boy?” Nat Williams wrote in his column. Once he became a star, most hardcore Elvis concert fans were white.

There were other ironies on old Beale. Cotton Carnival was a white high-society event featuring shirtless Blacks and mulattos as laborers or props. Blacks invented Cotton Makers’ Jubilee with its own parade and royalty … and whites crowded Beale Street to watch the parade. Ernest Withers was one of the first men to integrate the Memphis Police Force … but Blacks could not arrest whites. Until 1968, Beale Street’s wealthy neighbor The Commercial Appeal ran a front-page cartoon called “Hambone’s Meditations” that would have been welcomed by the KKK.

And young DJ and future author Louis Cantor, the self-described token white at WDIA (which was not on Beale but close to it), went by “Deacon” on his gospel show and “Cannonball” for R&B.

In real life he was Jewish.

**

To read more of John Branston’s posts, go to categories on the right side of this blog’s home page and select his name.

John Branston has been contributing to Smart City Memphis for four years. Before that he wrote columns, breaking news, and long-form stories for The Commercial Appeal, Memphis Flyer, Memphis magazine, and other print and online publications. He is author of the books Rowdy Memphis (2004) and What Katy Did (2017). He is a journalist and opinion writer. His stories are based on reporting, interviews and quotes supported by notes or a tape recorder. He has written about people who made Memphis what it is, for better and worse; about sleep issues and depression; about racquet sports; and about travel in the South and West.

**

To read more of John Branston’s posts, go to categories on the right side of this blog’s home page and select his name.

John Branston has been contributing to Smart City Memphis for four years. Before that he wrote columns, breaking news, and long-form stories for The Commercial Appeal, Memphis Flyer, Memphis magazine, and other print and online publications. He is author of the books Rowdy Memphis (2004) and What Katy Did (2017). He is a journalist and opinion writer. His stories are based on reporting, interviews and quotes supported by notes or a tape recorder. He has written about people who made Memphis what it is, for better and worse; about sleep issues and depression; about racquet sports; and about travel in the South and West.

Pleistocene journalism bluesman said no money no invue. NIL NBA and Grizz should pay for clayborn rebild. Context and connections. After all, it is called the blues.

Elvis breakthrough performance in Memphis was in 1956. The audience was almost all black.