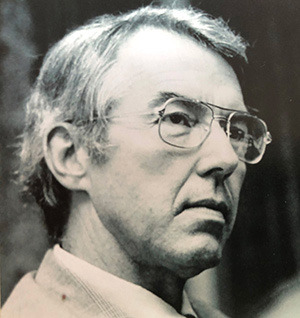

Ronald (Ron) Anderson Terry, proud Memphian who, as chairman and CEO for First Tennessee Bank for 22 years led it to become the state’s largest bank holding company died Monday.

Mr. Terry, 92, was a giant in the modern history of Memphis.

Most of all, he mobilized an entire city to aim higher, think smarter, and act bolder.

He may be remembered by many for his leadership at the bank, but for me, his civic leadership was even more impressive. He inspired a burst of civic energy and optimism that became a call for more CEOs to roll up their sleeves and work for a better city.

At a time when the Memphis economy was languishing in the late 1970s, he stepped forward to create a broad-based communitywide priority-setting process that set an ambitious agenda that changed the trajectory of the city. It was his leadership for the Memphis Jobs Conference that produced a new and better direction for the economy when economists were writing bleak predictions for the city’s future.

But his objective in rebooting the Memphis economy was to stimulate a citywide conversation about what Memphis could be and how to unify the city behind shared goals.

He envisioned Memphis as a tourism center and led creation of a hotel-motel tax that took tourism from an afterthought to a major driver of the Memphis economy. The same can be said for the Jobs Conference setting logistics as a major opportunity at a time when a modest overnight delivery company, FedEx, had moved to Memphis only a few years before but would come to be creator of modern global commerce.

The Jobs Conference also emphasized the higher potential of the Memphis port and the importance of stepped-up downtown redevelopment. It also put the importance of place on the agenda for the first time.

Shortly after the beginning of the 21st century, he articulated the vision for transforming the expansive Shelby County Penal Farm into a nationally significant Shelby Farms Park. He did not just talk about it. He personally lobbied county officials and although the first effort was unsuccessful, but it was an idea whose time had come. Because of him, today, Shelby County has a remarkable and popular 3,500-acre park at its center.

What I remember vividly about Mr. Terry is that he saw everyone as a potential colleague. There was no ego, no sense of superiority. He was a proud graduate of Memphis public schools with a Tech High School diploma. He was not the kind of person who spoke to someone while looking over that person’s shoulder to find someone more important. He really listened to what you had to say. He always remembered your name and treated everyone the same. He would say that if you got a telephone call from your family, you answered, regardless of who you were meeting with, because nothing matters more than family.

That was part of his special humility.

Once, after someone had offered an especially flowery introduction, he made the point that no one is irreplaceable. He said something like this: “There are people who come to the bank and they speak highly of me and always say how much I have helped them. But if I got hit by a bus tomorrow, they would come in, be told that I didn’t make it after being hit by a bus, and they would say, I hate to hear that, now, who can help me? That’s why you should always live for the moment and not get carried away with your accomplishments.”

Mr. Terry remains a model of leadership – business, civic, and family – and the results of his work became the foundation for modern Memphis.

In the worlds of business and civic duty, Ron Terry was a giant among giants. In the mid-70s, he and other business leaders such as the late Mike Rose and Pitt Hyde and, I believe, Fred Smith, would toss around ideas to make Memphis a 20th Century regional leader. Those ideas sometimes would become plans and those plans reality. Ron became the group’s spokesman because he never shied from talking with the press. He understood the importance of public opinion, and he made the press his friend. We’ve lost a great guy, but we’ll forever enjoy his legacy .