All the talk about the new Ford plant reminds me of when I worked in one.

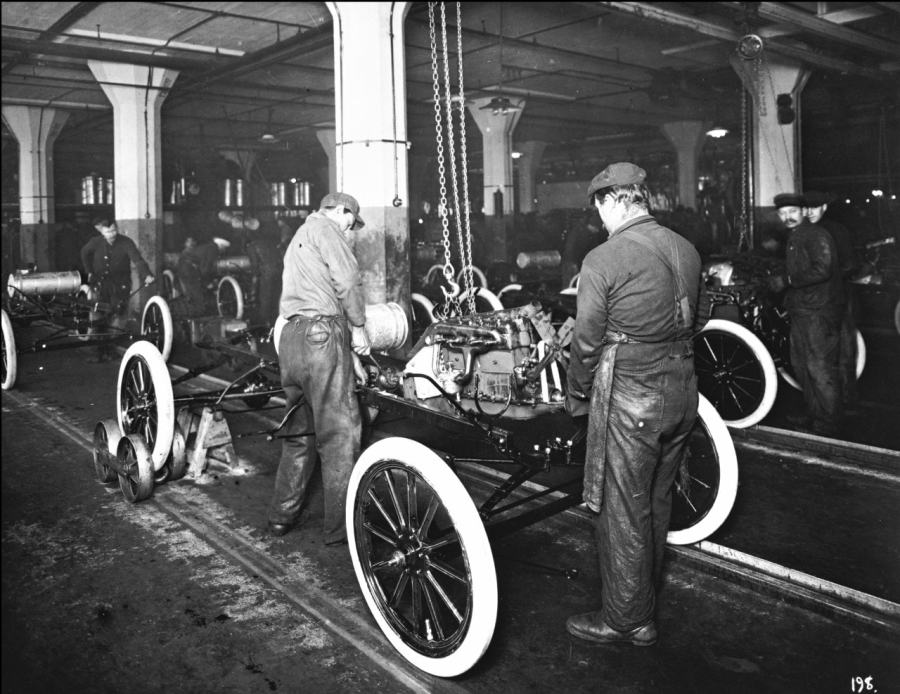

It was a “branch assembly plant.” Built in 1913 at a cost of $150,000, it was a gritty, no-frills box of a building. Five stories, 200,000 square feet. Auto parts were delivered to the fifth floor and the assembly took place as they moved down through the floors until a Model T emerged in the showroom on the first floor or was shipped to a dealership in the region.

It was one of about 30 similar plants built in major cities around the U.S. on the theory that it would reduce the costs of transporting the popular cars if there were only a few plants.

It was one of about 30 similar plants built in major cities around the U.S. on the theory that it would reduce the costs of transporting the popular cars if there were only a few plants.

By 1924, the Memphis Model T Plant was obsolete. The multi-floor assembly plant gave way to an expansive one floor assembly line. Ford closed the building and relocated to a 400,000 square foot plant at Riverside Drive and South Parkways.

From Assembling Cars to Assembling Newspapers

In 1932, the old Ford plant was sold and became home to the Memphis Press-Scimitar and The Commercial Appeal. Their circulation extended from the Delta to the Missouri Bootheel.

But that was years before I got there in 1970 to take a reporter’s job at the Memphis Press-Scimitar. It had a circulation of 150,000 and a subscription cost $1.95 a month. The building still had the feel of a old Ford plant.

The Ford auto assembly plant reincarnated into a newspaper assembly plant was located at 495 Union between the vibrant downtown to the west and an artery clogged with automobile dealers and hospitals to the east.

The first floor was the lobby, the second was for business services, the third was for The Commercial Appeal, the fourth floor was for the printing presses, and the top floor was for Memphis Press-Scimitar.

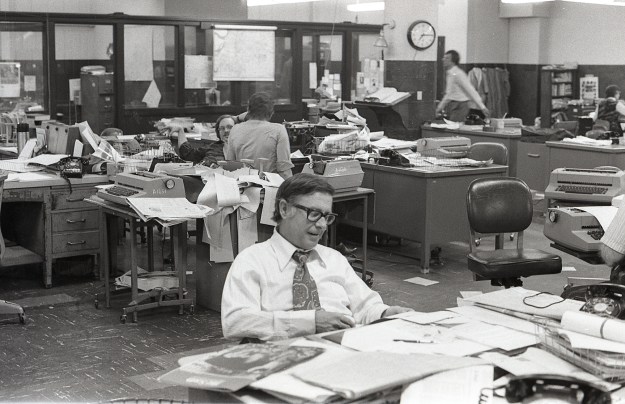

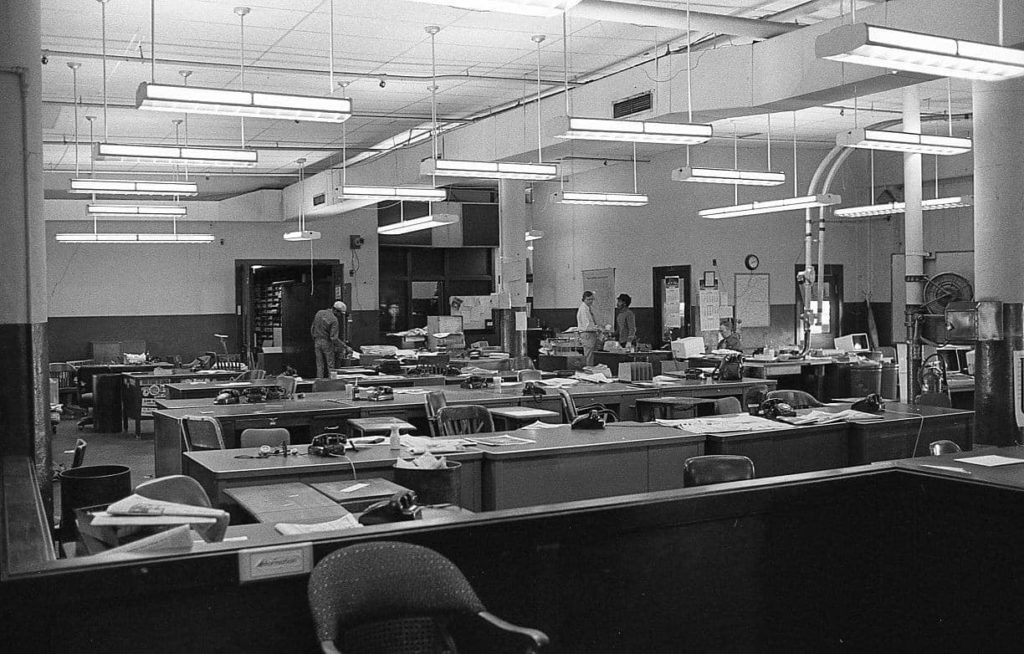

The large box of the Ford building remained: basic with no frills (except for editors’ offices). On the newspaper floors, dozens and dozens of desks were pushed head-to-head with the cacophony of reporters talking over each other as they called sources, took information from callers, and transcribed stories dictated by reporters at news events outside the building. Their stories were edited on the copy desk next to the windows facing downtown and could be extremely hot on summer days.

One Of A Kind

It was a different time and a world away from today’s daily newspapers (or what’s left of them).

The newspaper floors were a time capsule. They looked essentially like newsrooms from 30 years earlier in one of the classic black and white movies set in newspapers in the Thirties and Forties. And it was populated by an eclectic group of characters and eccentrics that no screenwriter could fathom.

The newspaper floors were a time capsule. They looked essentially like newsrooms from 30 years earlier in one of the classic black and white movies set in newspapers in the Thirties and Forties. And it was populated by an eclectic group of characters and eccentrics that no screenwriter could fathom.

There was the “ding, ding, ding” when news bulletins came over the teletypes. There were switchboards, classified ad salespeople, typesetters, typewriters, paper boys, letterpress printing, and hot type. When the presses rolled, the whole building shook. Radiators hissed, there were 16 feet ceilings and floors were 16 inches thick, and the elevator used most often by employees often didn’t make it to the top floor. There, the word colored had been covered up but could still be read on the restrooms nearby.

The towels in the bathroom were blank newsprint which we also typed our stories on. The air was often thick with cigarette and pipe smoke and the smell of alcohol sometimes wafted through sections of the newsrooms. After being edited on the copy desk, news stories were carried by pneumatic tubes to the press room where type was set and turned into aluminum plates for the presses. There were visits from politicians and celebrities and blasé reporters barely gave them a second look. The place hummed with activity, and there was always the feeling that another event would be taking place and would become an anecdote repeated time and time again.

Once Upon A Time

Six beat reporters downtown had their own offices there and I was one of them, sending in my stories by teletype from my Courthouse office. Later, downtown beat reporters experimented with a newfangled tool, a first generation fax. Reporters clipped their news stories onto a roller which spun rapidly and was accompanied by a shrill sound once the phone on the other end answered and until a copy of the story was received at the news desk.

Reporters at the Press-Scimitar were generally staring down a deadline. They were at 7:30 a.m. for the edition that went outside Shelby County, 11:30 a.m. for the edition delivered to home subscribers, and 2 p.m. for the newspaper boxes and the “news boys” on street corners.

There was the movie and book critic who put the books he didn’t want outside his office and rarely spoke with rank-and-file reporters; a columnist who could arrive to work inebriated and still turn out copy; the elderly reporter who had never done anything but write obituaries; the sports department with people like George Lapides, George Bugbee, Ken Jones, and Bobby Phillips; an editor who cared more about the society page than other sections of the paper and rarely appeared in the newsroom.

There was the movie and book critic who put the books he didn’t want outside his office and rarely spoke with rank-and-file reporters; a columnist who could arrive to work inebriated and still turn out copy; the elderly reporter who had never done anything but write obituaries; the sports department with people like George Lapides, George Bugbee, Ken Jones, and Bobby Phillips; an editor who cared more about the society page than other sections of the paper and rarely appeared in the newsroom.

The morgue was headed up by a small man who organized countless newspaper clippings, reporters’ notes, almanacs, and more. It appeared to be a room of chaos for everyone else but he and his assistant were largely able to deliver information to a reporter on any subject in short order.

Like almost everyone else in the newsroom, he was a character. He was once asked for a file on Muslims and when it wasn’t forthcoming, the reporter went back and said, “Do you have the file on Islam yet?” “Make up your mind,” he retorted.

The Cast Of Characters

The “slot” with the city editors and editing staff was on the west side of the reporters’ desks with a great view of downtown. One masterful editor could take a three-paragraph story, edit it, and return it, reduced to three sentences.

Managing editor Ed Ray was the embodiment of an old school newsman. He was gruff with a soft side. He began as a sports reporter when he was 14 years old, he was sports editor at 19, and was a managing editor by the time he was 24 years old. He was an old school newspaperman and impossible not to respect.

Kay Pittman Black was from a prominent Biloxi family and had such good sources in the civil rights movement that she was shadowed by the FBI and Memphis Police Department. Court reporter Roy Hamilton covered courts and his purple prose was featured in stories he wrote for true crime magazines under the name of Roger Hemingway. Ed Topp was an editorial writer and his family’s ancestral mansion was deteriorating on Beale Street across from the paper and its shell was occasionally a place for reporters’ lunches.

Michael Donahue was the most likeable copy clerk in history and would rise to become a reporter who seemed to know everyone in Memphis arts, entertainment, and culture. Eldon Roark and Robert Johnson who had their fingers on the pulse of the city and turned out daily columns. A reporter was taking information about a traffic fatality when he realized it was his mother.

All in all, it was a very white reporting group, which sadly reflected newspapers across the U.S. at the time.

There were so many more. Every person came with his or her own story. At its height, about 1,500 people worked in the newspaper assembly plant at 495 Union. The Press-Scimitar would be closed by Scripps-Howard in 1983 after its circulated had dropped to 80,000 – a circulation either of today’s Memphis daily newspapers would covet.

There were so many more. Every person came with his or her own story. At its height, about 1,500 people worked in the newspaper assembly plant at 495 Union. The Press-Scimitar would be closed by Scripps-Howard in 1983 after its circulated had dropped to 80,000 – a circulation either of today’s Memphis daily newspapers would covet.

The Real Newspaper

The old Ford plant was demolished in 1978 and its modern architecture replacement, according to former Commercial Appeal reporter Jimmie Covington, felt “more like an insurance company.” “The old building was the real newspaper,” he once said.

Former reporters who worked in the old Ford plant are scattered across the country now. Most of the surviving ones are in their 60s and 70s and their memories of a now bygone cultural institution vanish with each of their deaths.

If each of them would list their favorite memories of those days, it would fill a book.

Susan Adler Thorp, once a reporter at the Press-Scimitar, repeats one of her favorites:

“A man without a shirt on the press floor started banging a pipe on the presses. Someone called the psychiatric hospital and men in white coats charged out of the elevator on the fifth floor. They were carrying a strait jacket and said to (columnist) Bob Johnson, ‘we understand someone here has lost their mind.’ Bob turned in his chair and waved his hand toward the newsroom and said: ‘Take your pick.”

*****

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page and on Instagram for blog posts, articles, and reports relevant to Memphis.

Thanks again for a great column. Ford was an important plant for Memphis for many years — built on the initial back of the Memphis specialty in buggy frames and the vast supply of hardwood for the auto frame. It lasted in Memphis till 1958 — left about the same time the new Sears building opened at Poplar and Perkins. I have always heard that we lost the Ford plant due to the long-term local hostility to the UAW. That may not be true, but I have noticed that there is already some anti-UAW press about the new Ford plant.

Enjoyed the tales of the newspaper — I toured it as a young professor in the mid-1970s.

I, too, worked in the Ford/Memphis Publishing co. building. For The Commercial Appeal, not the Press Scimita. It was truly an experience. Coffee at the downstairs lunch counter like we had in the army, and a professional product every day that you’d better never find even one error OF ANY KIND. What a great newspaper it was, and what a staff of true professional journalists.

Enjoyed this article by the author who generously shared his knowledge and experience with cub reporters, including this one. I heard the following anecdote from more than one source so it must be true:

One CA employee whose eccentricities knew no limits went to the third-floor lunch room one morning and ordered a chili cheese hot dog and a Coke. The man behind the counter replied, “I’m sorry, it’s too early for that, but maybe I could get you a cheeseburger?” The indignant employee looked at the counterman and shot back, “A cheeseburger? Who eats a cheeseburger for breakfast?!”

Thanks, Larry for the kind comments. Great story.