It has been said that national politics is like a pendulum, swinging regularly from right to left. The same pendulum metaphor is equally adept for the philosophy of the Greater Memphis Chamber, where the pendulum regularly swings between consultants’ reports calling for greater emphasis on membership services and others calling for more involvement in public policy and governmental affairs.

Much of it is just the nature of the beast. As an organization that depends heavily on funding from the business community, the repositioning is often tied to a new pitch for more financial support.

These days, the pendulum has swung strongly to a philosophy that would involve the Chamber in important public policy discussions, and if done well, along the way, it will eliminate the need for public money, which often mitigates its willingness to wade into local politics. That is likely to change with the creation of the Chairman’s Circle, a super group of major donors pursuing five priorities and the creation of a Political Action Committee (PAC) supporting the kind of leaders the Chamber believes Memphis needs for a successful future.

There have been times in the past when Memphis has been much more assertive in the past in having a voice and influencing government policies – to the point that Chamber officials and city and county politicians sometimes stood toe-to-toe on opposite sides of controversial issues, ranging from the Miss Teen USA pageant to wide-ranging tax issues.

Shifting Position

In retrospect, some of the Chamber’s finest moments in the past 35 years have been in acting as a counterbalance to prevailing political thinking and in pushing back on what passes for conventional thinking. It requires a Chamber president who understands the governmental landscape and appreciates the nuances in influencing decisions. Sometimes it requires a statesman and sometimes it requires a bully, but at all times, it requires someone who understands the nature of money and power.

There is the hoary joke in local political circles that you’ll always win a race if the business community is supporting the other side. It was said again in the wake of the recent defeat of the Chamber-backed Pre-K referendum. In most political circles today, the Chamber and its leadership are seen as useful allies, but are never considered pivotal or vital.

The conversations under way at the Chamber could change all that, particularly if there is a PAC writing campaign checks in support of a specific agenda. There seems to be a new energy at the Chamber as it begins the process to hire a new president upon the retirement of John Moore, who led the organization from the brink of bankruptcy to the position that it can consider a more active persona. Until a new president is named, the Chamber’s capable vice-president Dexter Muller will serve on an interim basis.

At the Chamber, there are a number of new people – and most encouraging of all, new young people – who are involved in repositioning the Chamber to be more influential and forceful (not to mention, respected) when it comes to important community decisions. They are encouraged and joined by many of the old-timers at the Chamber who are concerned about the direction of Memphis and the need for stronger public leadership.

Historical Perspective

There are few Chamber staff members or board members today who remember when it went bankrupt in the early 1970s at a time when the Peabody Hotel was shut down and Beale Street was boarded up. When the Chamber emerged from bankruptcy, it had a new persona and its leadership was defined less by the interests of the white establishment and more by a group of Young Turks like Tiffany Bingham, who became the Chamber’s president from 1979 to 1984 (he also was chairman of the now legendary Memphis Jobs conference and a co-founder of Memphis in May International Festival).

Born into a life of privilege, Mr. Bingham felt the pain of the poor and fought for fair play and harmony and he was willing to challenge the business community to do more to improve the lives of all Memphians. When he brought these same sensibilities and uncommon honesty to the Memphis Chamber of Commerce, he made for a very different kind of Chamber executive. He wasn’t prone to kneejerk cheerleading although he was an unyielding supporter of his adopted hometown. He wasn’t given to the happy talk that’s prevalent in these jobs but he was given to the civility and consensus that welcomed everyone into important civic conversations.

Building on the momentum created by Mr. Bingham, the Chamber of Commerce brought back David Cooley who had led the organization in the late 1960s. The priorities given to him by his board: minority business development, expansion of low and middle-income housing, education and training and consolidation of government.

Mr. Cooley was known for the kind of reality checks that were valuable for the business establishment (even now, the 175 years of chamber chairmen are almost exclusively white and male). He said: “The greatest barrier to a better Memphis is ignorance. What are some of the problems of urban growth – a deteriorating central city, bad housing for a large percentage of our people, lack of skills training, poor workers mobility, undereducated and underemployed people in large numbers, token acceptance of blacks in decision-making.

A Needed Voice

Mr. Cooley left in 1995, and the Chamber of Commerce adopted an approach that was less assertive and more and more solicitous of local public officials as a result of significant funding from Memphis and Shelby County Governments. Meanwhile, the Chamber focus shifted from Mr. Bingham and Mr. Cooley’s hyperlocal concerns to more emphasis on increasing the number of members and their contributions and to the unthreatening public policy territory of regionalism.

The effectiveness of the Chamber and all local economic development efforts were called seriously into question in the first decade of the 21st century as the Memphis region lost more than 55,000 jobs. The voice of the Chamber was largely an echo of the mayors of Memphis and Shelby County. There was always the need for public funding, but there also is the Chamber’s reliance on tax freezes (if desired, the Memphis City Council and Shelby County Board of Commissioners can take back the authority given to the Industrial Development Board and Center City Revenue Finance Corporation).

The truth is that the Chamber-government relationship is always a nuanced ballet, one further complicated these days by the creation of the Memphis and Shelby County Economic Development Growth Engine (EDGE) which has blurred the roles and responsibilities traditionally within the purview of the Chamber of Commerce.

In addition, the Chamber’s challenges include finding a path to success at a time when top-down solutions are treated with suspicion; when many talented workers Memphis desperately needs feel that economic development plans are rarely about them but more often about blue collar workers and jobs, and when business community involvement can be as much negative as positive.

New Priorities

That said, the Greater Memphis Chamber’s interest in getting more involved in public policies and politics is good news. Memphis needs everyone to get out of the bleachers and into the game if we are to improve the city’s trajectory and that especially goes for the business community. Some cities we envy have based much of their success on dependable and consistent business leadership.

It is not always easy, it is not always pretty, and it requires businesspeople to learn more – and develop tenacity – about the rough and tumble rules of the political world. But as cities like Nashville have shown, if the business community is willing to get into the trenches (and stay there), it can be a positive factor in setting the right agenda and achieving it.

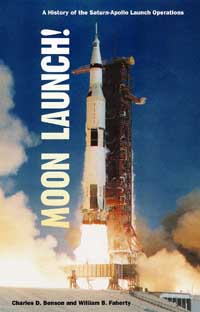

At its recent annual meeting, the Chamber announced what its priorities which it calls its “moon missions” — high school graduates ready to work in advanced manufacturing, diesel mechanics, welding or other high-demand trades (called Harvard Tech in what we hope is a short-lived name); pre-K; connecting Mid-South green spaces; adding 1,000 entrepreneurs in 10 years, and developing a long-range growth plan for the region.

Despite the hyperbolic comparisons to lunar launches, these are important priorities for Memphis, and more than anything, they could move Memphis from the bottom rungs of the rankings for major economic indicators after 15 years of lethargic performance.

As much as anything, Memphis needs smarter economic development plans and while the priorities might not take Memphis to the moon, they could position it more strongly to compete with its peer cities. Even better, success with these priorities could result in the Chamber providing the kind of engaged, consistent business leadership that can make the same kind of difference that we have seen in other cities.

My God. Chamber of Commerce cheerleading. This is what passes for ‘progressive thought’ in Memphis now? Smoky, backroom deals — That’s what the chamber knows and does. I’ve been in those meetings. They’re disgusting. Shame on you, ‘Smart’ City Memphis. Old debts to pay?

No debts to pay. We just think that the injection of younger leadership may be an opportunity for the Chamber to become more of a positive force. We will be the first to say it didn’t come to pass, but we’re hard-pressed to understand why we should be mired in the past. We’ve been tough on the Chamber when needed and we will undoubtedly do so again, but for now, we’re willing to be hopeful. That seems a good way to start the new year from where we sit.

A shake up of the central mission of The Chamber is most welcome. One need not look much further than the recent Memphis International Airport diabolical for a reason.

In Cincinnati when their airport was being downsized by Delta Airlines it was the Cincinnati Chamber that exerted considerable pressure upon CVG to maintain and attract air service. The Chamber led efforts to pre-buy tickets on the sole international flight and other key non-stops. And when the powers at CVG did not act quickly enough it was the Chamber that pressured the CEO of the Airport to step down.

Contrast that with Memphis where our Airports CEOs failure was rewarded with a position on the board at the Chamber.

However it should be noted that our local Fortune 500 companies and their top-tier employees (the highest paid in our city) are not exemplars of civic giving. Why does IP not partner with our local underfunded parks? Why does FedEx only lend it name to sports venues? Great cities are often made by powerful men and women. The rich and powerful in Memphis are largely missing in action.

Rose-

I agree with all you said but (maybe this is allowing too much of 2013 to muddy my opinions in 2014) I would settle for our Fortune 500 companies simply forgoing the standard practice of applying for PILOT support in their local operations.