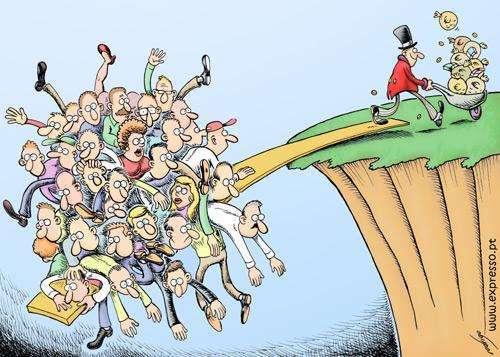

The Occupy movement has outposts in Memphis and in Nashville, but considering the damage done to our state from income inequality and one of the most regressive state tax systems in the U.S., what’s most surprising is that there isn’t an Occupy Tennessee movement.

No one has summed up the income inequality issue better than U.S. Senate candidate Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts:

“I hear all this, you know, ‘Well, this is class warfare, this is whatever.’ No. There is nobody in this country who got rich on his own — nobody. You built a factory out there? Good for you. But I want to be clear. You moved your goods to market on the roads the rest of us paid for. You hired workers the rest of us paid to educate. You were safe in your factory because of police-forces and fire forces that the rest of us paid for. But part of the underlying social contract is, you take a hunk of that and pay forward for the next kid who comes along.”

But, if the income inequality that has created a caste system of have’s and have-not’s isn’t negative enough, in Tennessee, it’s exacerbated by a tax structure build on the principles that the more you earn, the smaller percentage of your income you pay in state taxes.

A Deadly Intersection

The convergence of these two facts of life in Tennessee creates a perfect storm for low and middle income families. It’s a convergence that gets little, if any, attention from the Tennessee Legislature or the Haslam Administration despite trend lines showing this to be a serious problem for our state.

Strangely, the Republican Majority and the Administration subscribe to the myth-making flowing out of the Beltway that it’s in the best interests of all Americans for a slender percentage of Americans to play and benefit from special rules just for them.

A comparison of the average tax burden for the largest cities in 50 states paints a graphic portrait of our state’s tax structure’s inequities. To bring it local, consider this:

* Memphians who earn $25,000 pay 10.8% of their income in taxes

* Memphians who earn $50,000 pay 6.0% and 5.8% at $75,000

*Memphians earning $100,000 pay 4.9% and 4.3% at $150,000.

Getting Realistic on Taxes

In other words, the equity in the system is at best upside-down and at worst nonexistent.

For perspective, consider that the 4.3% in Memphis for families earning $150,000 compares with the following rates: Philadelphia, 11.1%; Providence, 11.4%; Baltimore, 10.1%; Atlanta, 10.2%; Columbus, 10.2%; Louisville, 10.0%; and Little Rock, 9.2 . The three cities with the least progressive state and local tax systems are Las Vegas, Nevada; Sioux Falls, South Dakota; and Memphis.

To aggravate the shift of the tax burden to lower earners, the Bush tax cuts sent 65% of the income gains to the top 1% richest people in the U.S. and produced the greatest income inequality in the history of Western Civilization. Our Gini index looks strikingly similar to Mexico’s.

The tax cuts added almost 50% of the total debt accrued in the decade, and if extended to 2021, they will cost more than $5 trillion, once again about half of the projected deficits. It’s an example of the fantastical thinking that passes for political leadership these days, particularly in our own legislature. We have little patience here for the doctrinaire – which is why we don’t watch Fox News or MSNBC – and for the echo chamber that creates the fiction that the Tea Party represents mainstream American thinking and gives them influence disproportionate to their size.

By the 1% For the 1%

Perhaps, the right-wing extremists, who stand in stark contrast to the strong traditions of Republican conservatism, know how short-lived their time in power will be. That’s why they are working so frantically to change government, the political process, and the free enterprise that balanced an obligation to the civic, and not just the corporate, good.

Joseph Stiglitz, in Vanity Fair, explains it well: “ “Some people look at income inequality and shrug their shoulders. So what if this person gains and that person loses? What matters, they argue, is not how the pie is divided but the size of the pie. That argument is fundamentally wrong. An economy in which most citizens are doing worse year after year—an economy like America’s—is not likely to do well over the long haul. There are several reasons for this.

“First, growing inequality is the flip side of something else: shrinking opportunity. Whenever we diminish equality of opportunity, it means that we are not using some of our most valuable assets—our people—in the most productive way possible. Second, many of the distortions that lead to inequality—such as those associated with monopoly power and preferential tax treatment for special interests—undermine the efficiency of the economy. This new inequality goes on to create new distortions, undermining efficiency even further. To give just one example, far too many of our most talented young people, seeing the astronomical rewards, have gone into finance rather than into fields that would lead to a more productive and healthy economy.

“Third, and perhaps most important, a modern economy requires ‘collective action’—it needs government to invest in infrastructure, education, and technology. The United States and the world have benefited greatly from government-sponsored research that led to the Internet, to advances in public health, and so on. But America has long suffered from an under-investment in infrastructure (look at the condition of our highways and bridges, our railroads and airports), in basic research, and in education at all levels. Further cutbacks in these areas lie ahead.

Unbalanced Behavior

“None of this should come as a surprise—it is simply what happens when a society’s wealth distribution becomes lopsided. The more divided a society becomes in terms of wealth, the more reluctant the wealthy become to spend money on common needs. The rich don’t need to rely on government for parks or education or medical care or personal security—they can buy all these things for themselves. In the process, they become more distant from ordinary people, losing whatever empathy they may once have had. They also worry about strong government—one that could use its powers to adjust the balance, take some of their wealth, and invest it for the common good. The top 1 percent may complain about the kind of government we have in America, but in truth they like it just fine: too gridlocked to re-distribute, too divided to do anything but lower taxes.

“It’s no use pretending that what has obviously happened has not in fact happened. The upper 1 percent of Americans are now taking in nearly a quarter of the nation’s income every year. In terms of wealth rather than income, the top 1 percent control 40 percent. Their lot in life has improved considerably. Twenty-five years ago, the corresponding figures were 12 percent and 33 percent. One response might be to celebrate the ingenuity and drive that brought good fortune to these people, and to contend that a rising tide lifts all boats. That response would be misguided. While the top 1 percent have seen their incomes rise 18 percent over the past decade, those in the middle have actually seen their incomes fall. For men with only high-school degrees, the decline has been precipitous—12 percent in the last quarter-century alone. All the growth in recent decades—and more—has gone to those at the top. In terms of income equality, America lags behind any country in the old, ossified Europe that President George W. Bush used to deride. Among our closest counterparts are Russia with its oligarchs and Iran. While many of the old centers of inequality in Latin America, such as Brazil, have been striving in recent years, rather successfully, to improve the plight of the poor and reduce gaps in income, America has allowed inequality to grow.

“Or, more accurately, they think they don’t. Of all the costs imposed on our society by the top 1 percent, perhaps the greatest is this: the erosion of our sense of identity, in which fair play, equality of opportunity, and a sense of community are so important. America has long prided itself on being a fair society, where everyone has an equal chance of getting ahead, but the statistics suggest otherwise: the chances of a poor citizen, or even a middle-class citizen, making it to the top in America are smaller than in many countries of Europe. The cards are stacked against them.”

Clearly building solely on regressive taxes is bad policy. However there are two things to note:

1) State income tax on wages/salary was held unconstitutional in TN. You’d have to challenge this in court or get a constitutional amendment to change it. Obviously a constitutional amendment is extremely unlikely.

2) While the state share should be reduced, it is probably in Memphis’ best interest to retain a higher local sales tax to capture income from tourists and commuters.