By Neal Peirce

WASHINGTON — June 17 marks the 40th anniversary of President Richard Nixon’s declaration of an American “war on drugs” — a struggle opponents say has cost $1 trillion, countless ruined lives, an eruption of dangerous crime rings, gross racial injustice, and precious little success in reducing drug use or addiction.

Observing the date, the Drug Policy Alliance is staging 50 events in cities ranging from New York to Los Angeles, Denver to Providence, Columbus (Miss.) to Inglewood (Calif.). Meanwhile, Students for Sensible Drug Policy is organizing a set of nationwide candlelight vigils to honor victims of the drug war.

But will it make any difference? Not if you check the White House’s brushoff of a just-released international panel report highly critical of the drug war, urging total U.S. and international rethinking of the issue including possible legalization of marijuana.

Members and signatories of the Global Commission on Drug Policy included a former Secretary General of the United Nations (Kofi Annan), a former U.S. Secretary of State (George Schultz), a former chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve (Paul Volcker), and the former presidents of Colombia (Cesar Gaviria), Mexico (Ernesto Zedillo), and Brazil (Fernando Henrique Cardoso- the commission’s chair).

One would expect a serious reply, indeed a careful reexamination of U.S. policy that’s driven so much of the international drug war. Here’s an eminent group declaring first that “the global war on drugs has failed with devastating consequences for individuals and societies.” Second that “vast expenditures on criminalization and repressive measures directed at producers, traffickers and consumers of illegal drugs have clearly failed to effectively curtail supply or consumption.” And third, that it’s time to “end the criminalization, marginalization and stigmatization of people who use drugs but who do no harm to others.”

Rather than engaging those issues, Gil Kerlikowske, President Obama’s drug czar, replied that “legalizing illicit drugs increases drug use and the need for drug treatment.” It’s an assertion clearly disproven by international experience. (Government-run heroin substitution programs for addicts have, for example, disrupted crime rings and reduced actual heroin use in both Switzerland and the Netherlands).

Second, Kerlikowske claims illegal drug use is associated with “fatal drugged driving accidents, mental illness, and emergency room admissions.” Technically, yes — sometimes. But the same’s true many times over due to alcohol misuse — and alcohol is a far more dangerous demon, complicit in vast numbers of attacks, rapes, even murders. We tried prohibiting alcohol by constitutional amendment in the early 20th century — only to learn people kept on imbibing even while prohibition spawned a vast criminal submarket and Al Capone-era surge of violent gang killings.

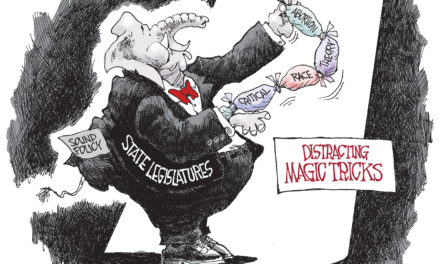

Kerlikowske says the White House no longer espouses “a culture war or drug war mentality.” But then he suggests no significant shifts, citing figures — disputed by critics — that overall U.S. drug usage has been cut in half in the last 30 years.

What’s not in the U.S. response to the international panel is a counting of the drug war’s horrendous toll.

Topping the list: the arrest and incarceration, in the U.S. and globally, of literally millions of people at the lower ends of illegal drug markets — petty sellers, “drug mule” couriers and poor farmers desperate for any source of income. As the panel notes, the arrests “fill prisons and destroy lives and families” without reducing drug availability or the power of criminal organizations.

Next, the American appetite for drugs. Because it’s so dangerous to smuggle drugs across the U.S.-Mexico border, we’ve spurred creation of a rash of Mexican drug gangs now responsible for an appalling 40,000 murders.

Third, racial injustice. As Jesse Jackson recently wrote (for the Chicago Sun-Times): “The war on drugs turned, early on, into a new Jim Crow offensive against people of color. Although whites abuse drugs at higher rates than African-Americans, African-Americans are incarcerated at 10 times the rate of whites for drug offensives. Millions have been deprived of the right to vote for being convicted of nonviolent crimes.”

We still await the day when any U.S. administration has been willing to debate those massive impacts. We still await a “change we need” from the Obama White House.

And then, the international panel notes, there’s our global complicity — that for 50 years, under a United Nations Convention on Narcotic Drugs, the U.S. government “has worked strenuously to ensure that all countries adopt the same rigid approach to drug policy–the same laws, the same tough approach to their enforcement.”

Yet this is precisely when the world so sorely needs new experiments, new learning, to deal with the complexities of drug regulation and today’s complex array of related health, justice, race and rights issues.

Surely it’s time to turn a fresh page.