We seem unable to shake off one of our most serious examples of civic lethargy: our tendency to take our most famous international export for granted as we talk about attracting and keeping creative workers – music.

Meanwhile, the rich get richer.

Up I-40, Nashville Mayor Karl Dean continues to drive new thinking about his city’s music industry, even to the point of gutsily suggesting that perhaps the county vibe was turning off creative types that the city needs. In response, he appointed the Nashville Music Council, a group of 50 high-profile musicians and industry leaders, with the audacious goal of making Nashville “the friendliest, most supportive city in America for creatives.”

One of Mayor Dean’s goals was even more heretical: to expand the annual CMA Music Festival to include genres other than country. Some of the other recommendations sound eerily like they may have been borrowed from Memphis Music Foundation, but on balance, the show of solidarity and focus on creative workers using music were impressive. After all, most of the music business centers on creative work such as writing, producing, performing, designing, and marketing, and it breeds the chemistry and connectivity that offers lessons for the creative economy at large.

The Largest 15 Music Cities

Of course, Nashville is the 800-pound gorilla. It has the highest concentration of the music industry in the U.S. and Canada and it is more than three times bigger than the second place city, Los Angeles. The 15 cities in U.S. and Canada with the highest music industry location quotients are:

1) Nashville

2) Los Angeles

3) Montreal

4) Toronto

5) Vancouver

6) New York

7) Oxnard-Thousand Oaks-Ventura, CA

8) Madison, WI

9) Atlanta

10) Quebec City

11) Winnipeg

12) Austin

13) Ottawa-Gatineau

14) Bridgeport-Stamford-Norwalk, CT

15) San Francisco

Creative industries in the U.S. like music tend to be driven by clustering and economies of scale and scope. One of the most important themes of new thinking about creative cities centers on authenticity, which is elemental to the character of our city but like music gets more lip service than action.

An Edge Strategy

As our colleague Carol Coletta has written, “Creative capital – new ideas and innovations, new designs, new ways of working and playing – is the fuel for the 21st century economic engine.” It’s the availability of talented people who are the keys to success in this economy, not raw materials or access to markets.

There are defining characteristics in a cultural scene that can make it attractive to creative workers: boundary crossing, definitions of culture and the promotion of inter-connections. That’s because there is multi-disciplinary and cross-disciplinary artistic and cultural expression; informal arts activities like public art, street festivals, gallery walks and farmers’ markets; cross-pollination between for-profit and nonprofit with people active on both sides of the street; and routine request for creative workers to be on task forces.

Our city has a way to go with better representation of young professionals and creatives on boards and planning task forces. There were some promising signs with the large committee considering the future of Beale Street as some folks from “the edge” and people not often seen on these types of public groups were mixed into the usual suspects.

It’s worth remembering the admonition of John Seeley Brown when he spoke to Leadership Memphis several years ago: “Innovation always comes from the edge. If you want innovation, don’t look to the center. That’s where you find conventional thinking and people invested in things as they are.”

Place Matters

That’s certainly been the case with the entrepreneurial and musical history of Memphis but somehow over the years, we lost sight of the reality of innovation. We’ve even rewritten our history to suggest that we embraced our famous music performers and recognized their genius from the beginning.

That’s the thing about creatives. It’s not just that we need them for our city to thrive economically. We need them to shake up the status quo, to provide new thinking and to shake off the vestiges of the ways things have always been.

Fundamentally, however, we must build a creative place. We should promote adaptive reuse of buildings to house creative companies; we should take culture to the streets and turn arts programming inside out; we should develop districts and neighborhoods that are Cultural Empowerment Zones with incentives and sweat equity options; we should develop design and development guidelines to encourage creativity and leverage the distinctiveness of neighborhoods; and more.

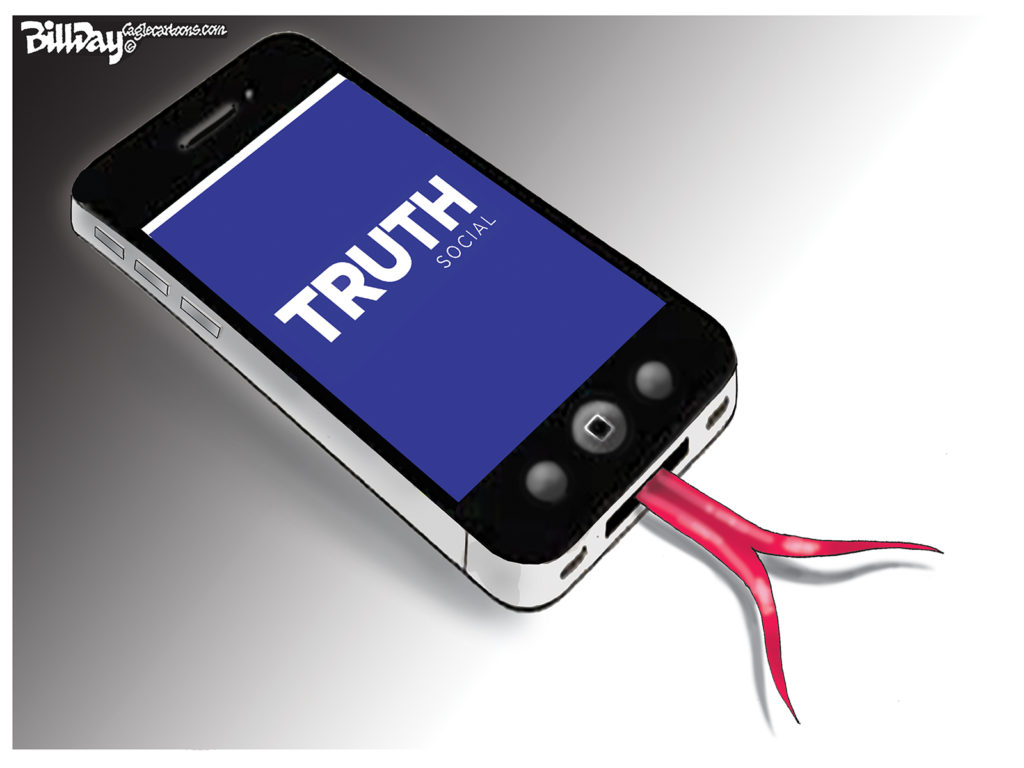

We have to push ahead until we find the tipping point, the point at which the rhetoric about young professionals, entrepreneurs and creative workers is transformed into solid, actionable things we can do. We seem to have become experts at incorporating the vocabulary of new ideas, but without changing our behavior.

Getting the Outsiders In

The damage from this is even greater than it would be in most cities, because in a city that prides itself for its authenticity, it’s the inauthentic behavior of rhetoric over results that discourages the very people we’re trying to enlist and encourage and the creative ecosystem that we are desperate for.

In Cities in Civilization, Peter Hall writes for 1,168 pages about how particular cities suddenly become exceptionally creative and innovative. He said some urban centers flourish, decline and reawaken periodically. He concentrates on about 20 cities from the Golden Age of Greek civilization to London’s glory days of capitalism in the 1980’s.

One of the featured cities is Memphis from 1948 to 1956. Calling our city “the soul of the Delta,” he writes about the collision of musical styles that produced rock and roll and transformed American music forever. He makes the case that Memphis’ burst of creative genius resulted from the combination of advances in technology, the rise of independent record labels and the impact of “outsiders.”

We tend to see all of this creativity as just a chapter in our history and we see it largely through a rearview mirror. The truth is that it has lessons just as potent for us today, beginning with seeing music as a vehicle to our creative economy.

Great analysis and you are exactly right – but give Memphis some credit. It is not surprising that some of Nashville’s “ideas” sound like they were Made in Memphis – they were. Nashville has become very interested in what is happening with Memphis Music. In fact, in their recent press articles they were “insulted” that the Memphis community should declare that “MEMPHIS MEANS MUSIC”……that anyone would dare to attack their MUSIC CITY title. We are getting our eyes out of the rear view mirror and have them planted squarely on the road ahead.

Dean Deyo

President – Memphis Music Foundation

There is so much lip service about building industry, attracting and retaining talent. Yet when there is money available it is usually sunk into a political backed non-profit vs. the industry. Typically the people who run these organizations have little to no experience. They bumble along wasting money and resources and dance when they are expected to.

Change in the INDUSTRY will come when you stop GIVING the money to people who are looking for ways to spend it and start SPENDING it with the people who who’s goals are to make more of it.

Don’t get me wrong many non-profits do great things but then again sometimes they are just bloated bureaucrats stuffing their faces with salaries they don’t earn.

Are we really supposed to believe that Nashville is looking over its shoulder at Memphis or giving the Music Foundation a second thought. We weren’t even on the list and they were #1. Get real.

What does the Mayor of Davidson County feel about these bold moves by the Mayor of Nashville? Are they cooperating? Is the Nashville Music Council a joint organization? Memphis and Shelby County would at least have meetings on such a bold move and appoint a joint study committee so our two Mayors could get on with the business of “governing”.

I second Christopher’s thoughts regarding our investments but also want to point out that serious music aficionados do recognize Memphis’ preeminence in musical creativity, the quality of which is directly proportionate to the economic depression and social repression from which it stems. Catch 22?

You know I definitely appreciate this sentiment (even though you did sadly not give a shout out to the theatre scene)and completely agree that creative capital is what we need, have, and underutilize in this city.

But, ironically, you missed one really critical element in building this type of town.

I contend (and I responded to the Mayor’s article in the flyer about promoting the arts here in the same way) we must first build strong, arts-based, SAFE FROM CUTS, programs in the public schools. In order to do this, money would have to be prioritized to rejuvinate the actual school facilities, attract and retain the teachers, and change the dialogue about the “importance” of these classes.

The most critical resource that is wasted in this city is its talented youth who venture elsewhere because the city did nothing to cultivate their skills… or worse, those who never even realize they have it.

Enrich the children who are already here, talented, and eager. Support them in their growth and then give them a community which they can stay and thrive in. They will change the dialogue of the city and they will be the lifebreath of this type of movement.

Your chart is full of BS. New York’s music business is not smaller than Nashville’s, and neither is Los Angeles. Been all those places.

“It’s worth remembering the admonition of John Seeley Brown when he spoke to Leadership Memphis several years ago: “Innovation always comes from the edge. If you want innovation, don’t look to the center. That’s where you find conventional thinking and people invested in things as they are.”

Yeah, well isn’t this the place that always argues that as long as they have a college degree, we’ll rubber stamp that hey CAN be creative?

Chris and Scott are 100% correct. Nailed it on all counts.

SCHOOL PROGRAMS don’t make money, but, they do teach children music, so they are NECESSARY.

Getting the government programs in the private sector out of the way, destroying markets already established by making products and services cheaper than they can be made to make a profit is bad policy every single time.

Our talented youth are mostly wasted, and coached to go down only ONE musical tunnel, ONE sports tunnel, Rap and Basketball. Sorry, but, it’s not a fit for everyone.

We’re just not all hiphop, sorry.

One act plays don’t do well.

Jaclyn: We don’t disagree with your points at all. We were just focusing on music on this post. Thanks for the insights.

Anonymous 10:17: It’s not our list. It’s a music industry list. There’s no conflict as far as we know between having a college degree (which is responsible for about 60% of a city’s economic success) and being on the edge.

Christopher – I completely agree! Lip service makes for great sound bites, but now it’s time to fish or cut bait. So often I hear folks in nonprofit complaining about how they are all fighting for part of the same ever-shrinking pie. Instead of funding organizations that rarely show they were able to use their piece of the pie to create actual, measurable change, let’s start funding the organizations that are working to make the pie BIGGER.