It is officially summertime in Memphis. Flowers are blooming, the temperature is going up, tens of thousands of people flood downtown for baseball at the best minor league stadium in the country and the panhandlers are back in force. As reliable as the swallows at Capistrano, they reappear to wander through downtown, some in constant conversation (often with themselves), to sleep in an alley or two, to follow downtown residents they have come to recognize and to torment the poor, bewildered tourists their radar always seems to fix on.

Other cities seem to be making strides in addressing this nuisance. Gone are the homeless people living in cardboard boxes above grates outside the federal buildings of Washington, D.C., and even Jackson Square in New Orleans, once panhandlers paradise, is free of harassment.

Few cities have resorted to anti-vagrancy laws, which has the deserved stigma from its legacy as a weapon in the South to deprive African-Americans of their rights. A more measured response is anti-panhandling laws, especially when coupled with social services that prepare people for re-entry into society by finding them jobs and training and diagnosing and treating mental disorders

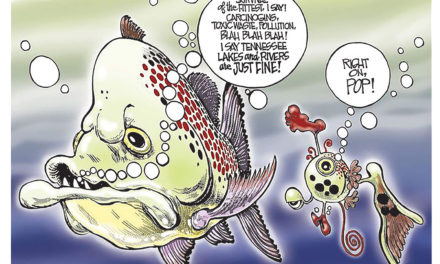

To set the record straight, this is not a problem with homeless people. The majority of them, probably less than five percent according to research, panhandle. Rather, it is an attack on behavior of a few who devalue and demean the common space that we collectively share, not to mention the smell of urine and worse that emanates from downtown parks and alleys in the summer. As the assault by one panhandler a few years ago against mental health advocate Nancy Lawhead reminds us, there are reasons to be wary. That is why Nashville’s new police chief made the fight against panhandling a priority. Cincinnati conducts a quarterly census and has passed laws against panhandling and for the removal of camping sites. Other cities that are actively addressing this problem include Little Rock, Atlanta, New Orleans, Austin, Orlando, Los Angeles and Las Vegas.

Back in Memphis, the word is out. There are panhandlers that come back to Memphis each year expressly because of its lax reputation and laxer enforcement. There is the man who regularly lives in Barboro Alley for the summer. There are the panhandlers who hitchhike back to summer in Memphis. There are the panhandlers who feel invincible.While there is the irritation to downtown residents that comes from the insistent begging, it is nothing compared to the discomfort that comes from watching a family from Spain or tourists from Denmark confronted by an imposing fellow who follows them down the street, talking loudly and with his hand in their faces.

With a tourism industry of $2.4 billion, it creates memories that do nothing to enhance the city’s reputation. But more to the point, it is more than a disservice to our guests. Most of all, it is a disservice to the panhandlers themselves. They deserve opportunities for to do better, and the first step is to get them off the streets so their needs can be addressed. Some say it is not compassionate to target them, but the sign of a compassionate city lies in offering these people the means to end their dependence on their skills as public nuisances.