History is like grief. It’s hard to understand it unless you lived through it.

That’s why it’s so hard now to judge Memphis photographer Ernest Withers’s role as an FBI informant during the volatile days of the civil rights movement in Memphis that climaxed with Dr. Martin Luther King’s murder. There is seemingly a clarity that comes with the passage of more than 40 years but it hardly results in an accurate assessment of the cast of characters from those volatile days.

The surveillance of Dr. King is by now old news, both by the FBI and the Memphis Police Department. In fact, agents were spying on him from a window at the fire station adjacent to the Lorraine Motel as the bullet tore through Dr. King’s throat at 6:01 p.m. April 4, 1968.

Today, living in a majority African-American county with an African-American president in the White House, it’s hard to summon up the hatred and fear that were part of every day life in Memphis during the garbage strike. At the time, the worst-kept secret in the city was that there were undercover agents and informants sprinkled through most civil rights organizations.

After all, it was only a few years earlier that the police department kept late Memphis Press-Scimitar reporter Kay Pittman Black under surveillance because she covered the civil rights movement and police commanders considered her, as a white woman, too friendly with black leaders.

The Movement’s Zelig

In other words, in those days, most civil rights leaders acted by the principle that everything they said was either being recorded by or reported back to MPD or FBI. It was widely assumed (most of all by the Invaders) that there were mainstream civil rights leaders providing information to agents and that explains the lack of emotion by them in the wake of The Commercial Appeal’s Marc Perrusquia’s Pulitzer Prize-worthy revelation that Mr. Withers was one of the FBI’s informants.

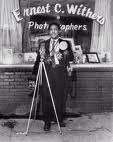

Anyone who covered the civil rights movement in Memphis knew Mr. Withers was the Zelig of the Movement here. Sometimes, there seemed to be at least two of him, because he seemed to pop up everywhere, accumulating a treasure trove of photographs of historic events.

While he was as ubiquitous as church rallies, most of his information came from eaves-dropping rather than the direct conversations as an insider. It was widely known that his growing family had put him under serious financial pressures and there was always a little bit of the hustle in him as well.

It’s been suggested by some that he was a primary source of FBI information about the Invaders, the college students who formed the Memphis version of Black Panthers, but the brain trust for that group hardly discussed their most sensitive strategies in front of Mr. Wither. More to the point, his reports were hardly needed in the first place since the FBI had an undercover agent inside the Invaders.

Myth-making

About a year ago, we helped to organize a University of Memphis of University symposium that revisited the role of the Invaders, and in talking with its leaders, they found it laughable that the FBI spent so much time and energy tracking their movements since as college kids, their pressing subjects could just as likely be about sex and marijuana as violent resistance.

Knowing that the FBI agent who worked undercover in the Invaders left for the CIA after Dr. King’s death, the Sixties militants were hardly rattled by the news that Mr. Withers was an FBI snitch. Back in the day, it was a pretty safe bet that some well-known mainstream Memphis civil rights leaders were also providing information to the FBI. In truth, it was an understandable strategy for them. They could give information on the Invaders and in the process position themselves as the moderates that the local establishment should support.

In this way, if the Invaders had not existed, Memphis civil rights leaders would have had to invent them. In meetings with everyone from law officers to business leaders, the civil rights leaders held up the Invaders as wild-eyed revolutionaries – they were revolutionaries but hardly wild-eyed – as a way to enlist support. The message: it’s us or them.

As a result, there always seemed to be another rumor about the Invaders, and the news media willingly perpetuated their reputation as violent thugs. It was said that they were armed with machine guns and planned to mow down the opposition. They were about to rob banks to pay for the revolution. They were quoted as saying that blood needs to run in the streets of Memphis and they were willing to make it happen. They were charged with leading the high school walk-outs by city school students. They were accused of disrupting demonstrations by the black ministers. They were blamed for the violence that erupted during Dr. King’s first march in Memphis.

Worn Down

They were the militant yin to the mainstream movement’s yang. They were the tough talk to the leaders’ persuasive rhetoric. They were the grassroots organizers to the movement’s community mobilizers. But, most of all, they created a palpable fear in Memphis at large that kept white power brokers at the table talking to civil rights that were seen as more reasonable and more powerful.

The Invaders – officially named the Black Organizing Project – were a youth movement, and while they are often a footnote to the 1968 historic events in Memphis, they were in truth key players to what took place here. In February, 1968, their grassroots group – named for the popular television program, The Invaders, in which aliens passed as humans by day but remained totally different when together at night – was a year old when the sanitation strike began, and already, they were a force to be reckoned with in the neighborhoods

Now, wearing 40 years of world-weary experience, they exude a “we’ve seen it all” attitude as they reflect quietly on those volatile days when Memphis seemed to be coming apart at its seams. They are reflective and philosophical, and only occasionally does something spark the old fire in the belly that characterized their student and neighborhood organizing back in the day.

It was a different day. The chairman of the Chamber of Commerce could say with no fear of impunity: “You can’t take these Negro people and make the kind of citizens out of them you’d like. It’s going to take maybe 40 years before we can make any real progress.”

Conspiracies

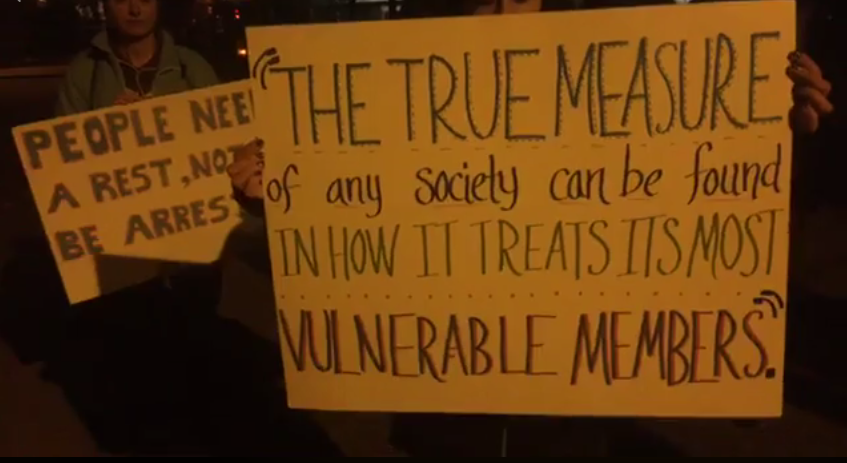

While mainstream civil rights leaders talked about settling the strike, the Invaders called for more self-determination by African-Americans, for more disruption of the status quo and for a new racial consciousness and pride. As a result, their military jackets and their berets became symbols of grassroots anarchy.

On April 4, only a couple of hours before a bullet killed Dr. King and the Memphis that he had come to know, the Invaders were asked to leave the Lorraine Motel following an argument with some members of Dr. King’s camp. Shortly after arriving at their South Memphis apartments, they would learn that Dr. King had been shot.

They would also learn that the APB that went out from Memphis Police Department was for a Mustang driven by the shooter fleeing the scene. The leaders of the Invaders also drove the same color Mustang, and they remain convinced that they were being set up for the assassination.

When they today connect the dots of conspiracy, a line runs from the Mustang to the removal of Ed Redditt from the fire station overlooking the Lorraine Motel where he was handling surveillance of the civil rights leader. It also connects to the undercover FBI agent who was building a file on The Invaders – files they have still not seen today – and who ended up at the CIA.

Following the murder of Dr. King, most of the Invaders left Memphis for a time, disenchanted by the events, harassed by the police, locked up by the FBI on any possible charge, maligned by the media and fatigued by the speed in which history overtook and destroyed them.

typical memphis.

stuck in 1968.

so sad.

How typical to use that hoary phrase, “typical memphis,”