By Scott Newstok

When Thomas Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence toured the nation on a “Freedom Train” in 1947-1948, Boss Crump’s Memphis was one of only two cities whose scheduled visits were bypassed. (The other was Bull Connor’s Birmingham.) Why? The exhibit’s national organizers were dismayed at Memphis city leaders’ insistence on segregating visitors, apparently out of fear that “somebody might get the idea that American Freedom should also apply to Memphis and Shelby County.”

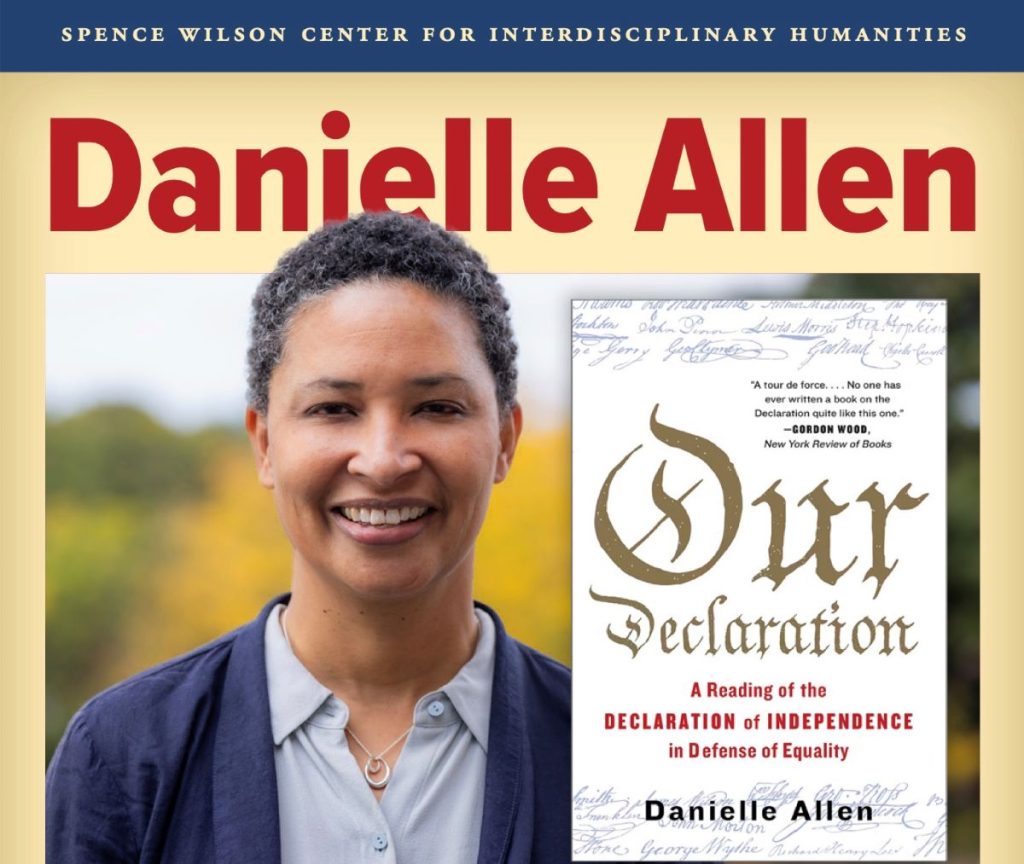

American Freedom is now coming to Memphis. In honor of the 250th anniversary of the 1776 Declaration, the Spence Wilson Center for Interdisciplinary Humanities at Rhodes College presents a free public lecture on Thursday, September 18 (6pm, McNeill Concert Hall) by Dr. Danielle Allen, the James Bryant Conant University Professor at Harvard and director of the Allen Lab for Democracy Renovation.

This event is free and open to the public, but all attendees must pre-register using this link:

https://fs22.formsite.com/webmanagerrhodesedu/4i7kriyth1/index

Allen, who’s both a renowned scholar and public policy advocate, makes the radical proposition that the best way to commemorate the Declaration is by simply reading it—yet reading it slowly and closely.

Combining a personal account of teaching the Declaration with a vivid evocation of the colonial world, Allen’s award-winning book Our Declaration reveals our nation’s founding text as not a catechism to be memorized but an animating force that can and did change the world. Challenging conventional wisdom, Allen boldly makes the case that the Declaration is a document as much about political equality as about individual freedom.

As an English teacher, I love the way that Our Declaration attends so carefully to language. Allen takes us down to the level of a word (what exactly does “course” mean in “the course of human events”?), or even a punctuation mark (is that a comma after “the pursuit of happiness,” or was it rather a smudged semicolon?).

She brings to bear the full breadth of humanities methods (close reading, archival research, ethical reflection) and disciplines (ancient Mediterranean studies, history, languages, literature, philosophy, politics, religious studies) on this crucial document. Reading the Declaration sentence-by-sentence, clause-by-clause, word-by-word, Allen crafts a moving memoir about her teaching in The Clemente Course in the Humanities.

Our city’s history has long been intertwined with the Declaration. While Tennessee didn’t become a state until two decades after the signing of the Declaration, and Memphis wasn’t incorporated until 1819, “the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff was well-known to native Americans and explorers from France and Spain.” As Allen acknowledges, the Declaration “provided tools for liberating some and dominating others,” including the indigenous peoples who thrived long before colonists and traders came to our area.

Allen also wrestles with the cruel irony of how segregationists revised the Declaration’s aspirational conjunction of “separate and equal” to the doctrine of “separate but equal.”

(Our state’s 1861 vote for secession called for a “Declaration of Independence and Ordinance dissolving the Federal Relations between the State of Tennessee and the United States of America.”)

The first gallery in the Memphis National Civil Rights Museum starkly underlines the incongruity between the Declaration’s lofty words its slaveholding authors. Called “A Culture of Resistance: Slavery in America 1619–1861,” the exhibit juxtaposes the brutal history of Atlantic Slave Trade with the famous passage from the Declaration “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Yet the Declaration also provided a lexicon for fighting oppression. As Rhodes Provost Timothy Huebner has documented, “Almost from the founding of America, black leaders claimed the words of the Declaration of Independence and used them to promote the rights of African Americans.” Some notable examples include James Forten (1813) and David Walker (1829).

Frederick Douglass’s influential 1852 speech drew encouragement from the Declaration, which he called “the RINGBOLT to the chain of your nation’s destiny”—characterizing its words as a kind of unfulfilled promise, or overdue payment. University of Memphis historians Beverly Bond and Susan O’Donovan have argued that the 1866 Memphis Massacre “galvanized Congress into taking the steps that moved Reconstruction . . . [to] a full-blown commitment to the ideals sketched out in the Declaration of Independence.”

A century later, Martin Luther King, Jr. repeatedly cited the words of the Declaration, whether recalling it as “a promissory note” in his “I Have a Dream” speech or aligning himself with Jefferson as a so-called “extremist” in his Letter from a Birmingham Jail. In 1967, King delivered a sermon titled entitled “Declaration of Independence from the War in Vietnam,” in which he noted that even though the Vietnamese “quoted the American Declaration of Independence in their own document of freedom, we refused to recognize them.” And in his final “Mountaintop” speech in Memphis in support of the sanitation strike, King praised student protesters for “standing up for the best in the American dream and taking the whole nation back to those great wells of democracy, which were dug deep by the founding fathers in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.”

Across the globe, the Declaration has influenced a startling array of movements. Immigrants to Memphis have been inspired by the Declaration, from the Poland-born pro-suffrage legislator Joe Hanover to the Czech immigrant Theodore Ohman, who created a lithograph reproduction of the Declaration in Memphis in 1942. Ohman’s print required a complex technical process, with the image derived from the last authorized photograph of the original, which was made in 1903.

Rhodes College’s Archives holds a copy of Ohman’s “Declaration,” which will be on display at Allen’s September 18 lecture. Early arriving guests will receive free pocket copies of the Declaration, as well as hear a selection of music that was enjoyed by (or written by!) the Declaration’s original signers, as part of Thirty Days of Opera.

**

Scott Newstok is Professor of English and Executive Director of the Spence Wilson Center for Interdisciplinary Humanities.

i did not know until reading this that declaration says separate and equal