Nothing is certain but death and taxes, so says the proverb. Here in Memphis, it is just as accurate to say nothing is certain but death and tax freezes.

Here, tax breaks for businesses, real estate developers, and housing seem as immutable as taxes themselves.

Critics complain that PILOTs — Payments in lieu of taxes — are taking taxes away from schools and vital public services. Boosters insist they are essential for the Memphis regional economy, which is fighting to keep pace with places it once outflanked.

Few government policies elicit more questions, which is unsurprising, considering PILOTs waive about $700 million in taxes every 10 years and are powerful tools to influence economic growth and opportunity if strategically aimed at the right businesses and at increasing incomes. ‘Strategic’ is the key word since numerous studies conclude at least 75 percent of the companies receiving tax breaks would have located even without the tax break.

Here, over the past 25 years, city and county governments have appointed multiple committees to evaluate and improve PILOT programs. There’s another assessment underway now in a Shelby County Board of Commissioners committee. Past experiences have taught that when changes are made, they were routinely abandoned after pushback from business and real-estate interests.

Committees tend to concentrate on EDGE because its PILOTs garner the most headlines. However, EDGE is only one of nine public boards with the power to approve PILOTs, and the amount of EDGE’s tax breaks only accounts for about half of the taxes that are waived. Its 266 PILOT agreements — more than Nashville, Knoxville, and Chattanooga combined — waived $19.4 million in county taxes in 2024 and an estimated $14 million in Memphis taxes (city government doesn’t report lost revenue from PILOTs, so estimates are necessary — but the county trustee’s report on PILOTs is definitive).

Meanwhile, 98 PILOTs approved by the Downtown Memphis Commission and 127 by the lesser-known Memphis Health, Educational, and Housing Facility Board totaled $17 million in county taxes alone in 2024. Then, too, Industrial Development Boards in Arlington, Bartlett, Collierville, Germantown, and Millington and Shelby County Health, Educational and Housing Facility Board also approve PILOTs.

They follow a rule set by city council and county commissioners: A company receiving a PILOT pays only 25 percent of its tax bill and the other 75 percent is waived for up to 20 years. There is also the retention PILOT that gives new PILOTs of 15 years to companies with previous tax breaks — think FedEx and International Paper — which sends the message that the companies that know us best still need PILOTs to value us.

Most smaller municipalities waive minor amounts of taxes — except for the Industrial Development Board of Collierville, whose 10 PILOT agreements for $3.1 million regularly reward the recruiting of businesses from Memphis. Like every board that approves PILOTs, each one waives that city’s taxes, but also Shelby County’s — which means that Memphians pay the bulk of the county tax break that encouraged the company to move from their city.

A recent example is a six-year PILOT of $1.5 million approved for a medical clinic although it bought its property 11 months earlier and Collierville had already approved building plans and the development contract. As former County Mayor Jim Rout once reasonably asked: “What is the benefit to Shelby County Government when a company is only changing its ZIP code in Shelby County, but county government is losing taxes?”

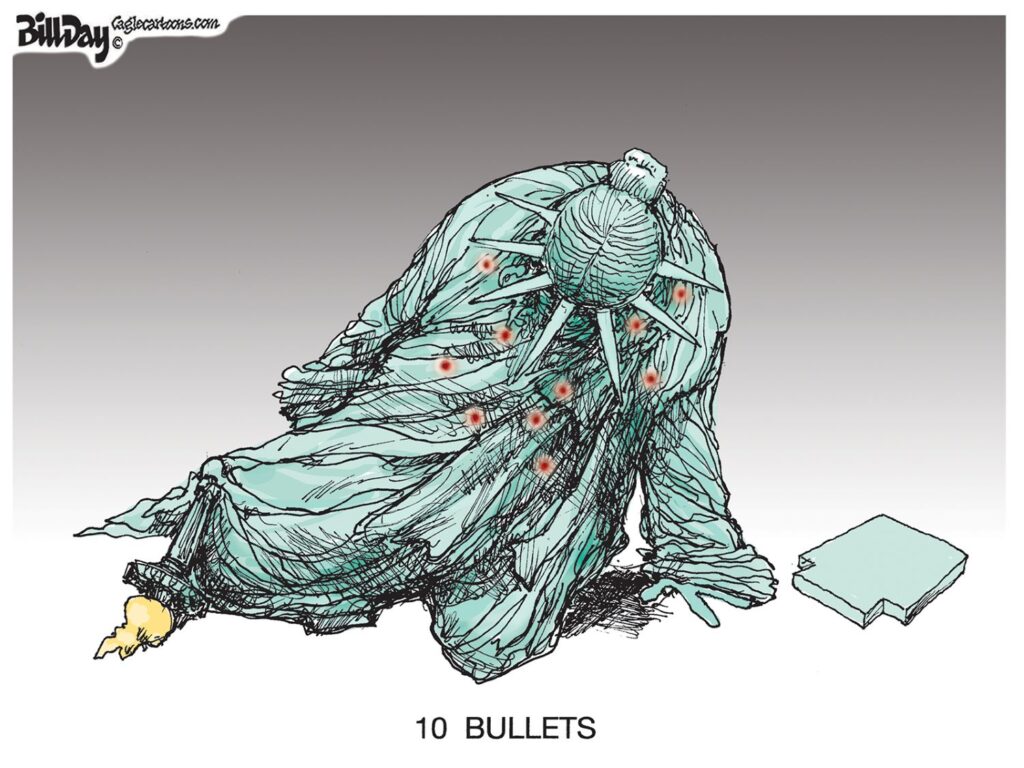

Cities’ ability to waive county taxes for companies moving inside Shelby County is but one peculiarity of PILOT rules. Most glaring is the fact that every PILOT is also giving away money that would otherwise go to schools.

While every dollar given in an unnecessary or excessive PILOT is a dollar that can’t be spent on education, workforce development, quality of life, and other drivers of economic success, PILOTs more directly affect school funding. Some places like Hamilton County (Chattanooga) safeguard funding for schools by backing that money out of any incentives they approve.

PILOT terms long ago were reduced from 100 percent to 75 percent with the intention that the money from the reduction went to schools; however, schools are still shortchanged because 60 percent — not 25 percent — of the county’s property taxes is spent on education. A reasonable estimate of the amount schools loses from PILOTs every 10 years is about $175 million.

Meanwhile, the obscure Memphis Health, Educational, and Housing Board, which provides tax breaks and tax-exempt bonds for low-income housing, is known for its resistance to transparency and is connected to some high-profile evictions and disturbing complaints from residents. And the Downtown Memphis Commission issues PILOTs for apartments although occupancy rates have been 95 percent since 2018, raising questions about the market need for the incentives.

City council and county Board of Commissioners delegated their authority to waive taxes to the PILOT-granting boards. PILOTs are not even discussed during stressful budget hearings where they are scratching for new revenues. The local legislators don’t even ask for regular reports on the impact of the PILOTs.

That’s arguably the greatest peculiarity of all.

Note: This post was published as my City Journal column in Memphis magazine in July.

Excellent summation of our problems with PILOTs. Smart City and several others have clearly stated these issues over the years. Unfortunately, those who can change our tax incentives to properly work for our actual benefit continue to ignore basic economics and any realistic knowledge of business investment decidion-making.

Excellent summation of our problems with PILOTs. Smart City and several others have clearly stated these issues over the years. Unfortunately, those who can change our tax incentives to properly work for our actual benefit continue to ignore basic economics and any realistic knowledge of business investment decision-making.