By John Branston

I see where the Memphis Redbirds and AutoZone Park are having a hard time.

I see it in the scant coverage in the local media. But mainly I see it with my own eyes through the fence that separates the downtown Fogelman YMCA from the ballpark’s left field, giant scoreboard, grassy berms and empty seats. The Y is my daycare center, evening my departure time, and baseball my first love, so I watch a half inning or so.

As downtown buildings go, AutoZone Park, which opened in 2000, has had a decent run. The Pyramid made it 13 years as a sports facility, sat empty for a few years, and is now Bass Pro. Beale Street Landing riverboat dock is closed. 495 Union Avenue is closed and so is Hooters. So much for boobs.

Minor-league baseball has had a good run since 1900 when the Chickasaws (Chicks) and Negro League Memphis Red Sox played at Russwood Park until fire destroyed it in 1960.

Memphis has been host team to two superstars who played baseball. The careful wording is deliberate and important. One was Bo Jackson of the 1986 Memphis Chicks, possibly the greatest all-around athlete of my lifetime. The other was Birmingham Baron Michael Jordan in 1994, possibly the greatest basketball player of my lifetime but also one of the worst impersonators of a professional baseball player. He was on sabbatical from the NBA. He played right field, the redoubt of “worstguyontheteam” for generations. He hacked at curveballs like a drunk with an axe, loped gamely to first base to run out grounders, and butchered fly balls in the lights. I wish I hadn’t seen it.

This was before downtown AutoZone Park and the Redbirds succeeded the Chicks and Tim McCarver Stadium at the old fairgrounds. It exists because a tough Memphis businessman and former high school ballplayer named Dean Jernigan willed it into existence and insisted that it be built to the highest standards downtown rather than out East.

The love affair didn’t last much longer than 25-cent beer nights, mascot races, or McGwire’s steroid-juiced muscles. It was not for lack of trying. But the big-league Grizzlies moved here, cheap drunks got out of hand, and a game in which the ball is in play about ten minutes in three hours could not compete with screens and video games.

And sports self segregated.

Baseball, a segregated white sport in the pros until 1947, is today primarily a white sport in Shelby County and DeSoto County, just as basketball is primarily a Black sport. The Redbirds recognized this and hired Reggie Williams (a former major-leaguer and Southside High graduate) to kickstart Return Baseball to the Inner City (RBI). He did his darnedest but it didn’t stick.

Which is to say that the appeal of baseball is mainly nostalgic. The great sportswriter Red Smith pointed this out in 1955. Organized baseball had just left South Florida (and would soon leave Brooklyn and the Polo Grounds in New York). Smith, as ever, did not let sentiment trump journalistic honesty.

“The only reason baseball is our national sport, instead of cricket or soccer, is that practically all American males play baseball or its equivalent – stickball on the city streets, softball on the school yards – when they are young … When they grow up they watch the games because the spectacle restores their youth and warms them with nostalgic memories of the fun they had as kids.”

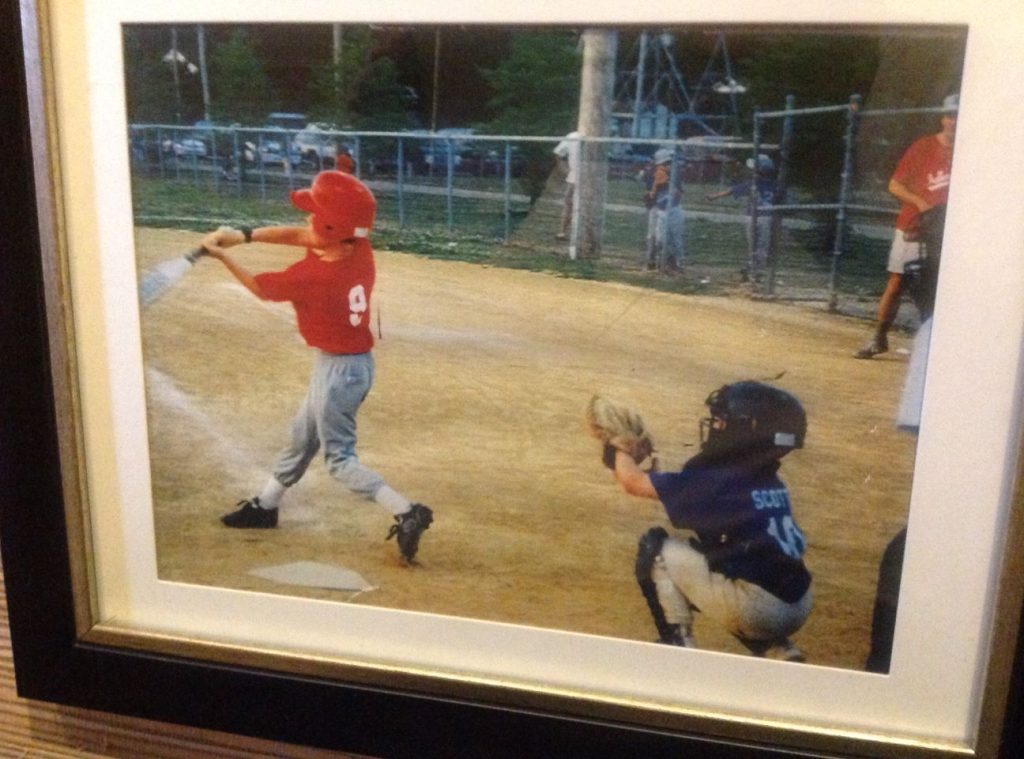

Damn, Smith was good. And damn, it was fun collecting cards, playing home-run derby and work-up, rubbing saddle soap into a glove, and watching a ten-year-old catch a liner.

***

To read more John Branston’s posts, go to categories on the right side of this blog’s home page and select his name.

John Branston has been contributing to Smart City Memphis for four years. Before that he wrote columns, breaking news, and long-form stories for The Commercial Appeal, Memphis Flyer, Memphis magazine, and other print and online publications. He is author of the books Rowdy Memphis (2004) and What Katy Did (2017). He is a journalist and opinion writer. His stories are based on reporting, interviews and quotes supported by notes or a tape recorder. He has written about people who made Memphis what it is, for better and worse; about sleep issues and depression; about racquet sports; and about travel in the South and West.