We’ve heard a great deal in recent years about how population growth is a top priority for Memphis to the point that it spawned yet another reason to waive taxes, this time for apartments that were supposedly the magnet for in-migration.

Back on November 26, 2018, we blogged about how population growth is often used as a proxy for economic growth:

“Most U.S. cities have acted on the article of faith that population growth is in and of itself beneficial and that the faster the growth, the greater are the economic benefits, and larger population is hailed as the cure for cities’ ailments, particularly when it comes to the need for local jobs.

“And yet, when Eben Fodor, a consultant on land planning and growth management, looked at the 100 largest U.S. metros from 2000-2009, he used the annual population growth rate and compared it to the unemployment rate, per capita income, and poverty rate. He concluded that the conventional wisdom that growth generates economic and employment benefits was not supported by these data.”

All of this is a discussion worth having in Memphis, because of our community’s habit of using an issue – think consolidation – that seems to paralyze us from taking the kind of bold actions that we need to address problems that are structural in nature. For many years, we said that the presence of both city and county governments was what prevented Memphis from taking its place among the country’s most successful cities, ignoring the fact that 99% of major cities had the same similar government structure as ours.

Well-known American urban studies theorist Richard Florida, whose books introduced the concept of the creative class (and whose first application of his research applied to Memphis), continues to suggest that population decline is not the kiss of death for cities. Considering that our demographic trend lines suggest that it may be optimistic to assume Memphis’ population loss is going to turn around, it’s a position worth discussing….just in case.

How Some Shrinking Cities Are Still Prospering

The phrase “shrinking cities” conjures up images of economically ravaged places, defined by declining populations and massive job loss. A USA Today report earlier this year listed declining Rustbelt cities like Johnstown, Pennsylvania; Youngstown, Ohio; and Pine Bluff, Arkansas as among America’s 25 fastest-shrinking cities. These places not only suffered from massive population loss, but high rates of unemployment and violent crime.

But a new study suggests that shrinking population and economic decline don’t always come hand-in-hand: A striking subset of cities with declining populations are in fact economically prosperous. The report by Maxwell Hartt, my former University of Toronto colleague who is now at Cardiff University, examines the economic performance of American cities with shrinking populations, looking at their performance on indices of income, unemployment, job growth, and economic inequality from 1980 to 2010.

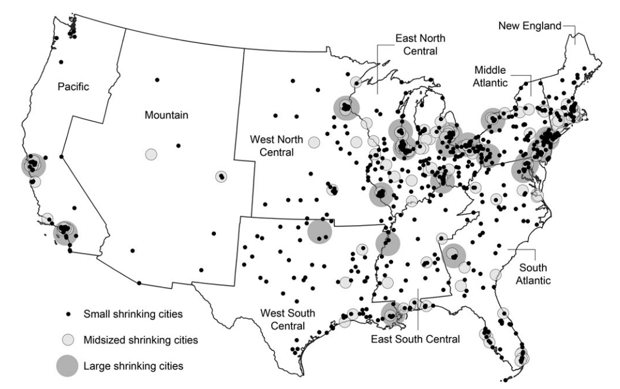

Other studies have found that more than 40 percent of U.S. cities (those with at least 10,000 residents) qualify as shrinking cities, having lost population between 1980 and 2010. But Hartt estimates the real number is closer to 35 percent, or 886 cities, because he disqualifies cities which saw their land areas or census boundaries redrawn and decrease.

The map below, from the study, charts all 886 shrinking cities. The Rustbelt has large numbers of them, along with the Sunbelt and the Northeast. Less than a fifth of shrinking cities are principal cities (cities that are the largest incorporated place in a core-based statistical area or meet a threshold both for population and working population). Eighty percent of them are suburbs or smaller communities.

(Annals of the American Association of Geographers)

In the next map, Hartt charts the location of prosperous shrinking cities. Overall, Hartt finds that more than a quarter of shrinking cities (27 percent) can be defined as prosperous, having economic indices—the four factors mentioned earlier—greater than their regional average. Just 4 percent of prosperous shrinking cities are principal cities; the vast majority are suburbs and smaller places. For example, the affluent suburb of Mountain Brook, Alabama, has faced population decrease while maintaining high income and talent levels.

(Annals of the American Association of Geographers)

Not surprisingly, a relatively large percentage of prosperous shrinking cities are clustered near large, successful metros like New York, San Francisco, Chicago, and Miami. Over 30 percent of the shrinking cities in the Pacific, Mountain, Middle Atlantic, and New England census divisions are prosperous, whereas those in the West North Central and West South Central divisions were least likely to be prosperous, only about 11 to 12 percent.

In Hartt’s words, “the absolute number of prosperous shrinking cities appears to be relatively proportional to the number of shrinking cities. The relative proportionality suggests that prosperous shrinking cities might be a consistent subset of shrinking cities, rather than a geographically distinct phenomenon.”

The study found no connection between the prosperity of cities and either the size of their population or the severity of population loss. “Remarkably, the severity of shrinkage was found to have no effect on income,” Harrt writes. “The lack of relationship between severity, persistence, and income demonstrates the diversity and complexity of urban shrinkage processes.”

The researchers find that the main thing that distinguishes prosperous shrinking cities from a solely shrinking city is a particular type of talent. The strongest factor is college grads: 97 percent of prosperous shrinking cities had a higher proportion of college-educated individuals than their regional average.

This reflects the ongoing march of what Bill Bishop long ago dubbed the “big sort.” It’s not just that places are losing or gaining people in general. They’re specifically losing less-educated people while gaining more-educated people, a sorting process often exacerbated by expensive housing. Population growth is a crude measure of prosperity: As long as a place attracts or retains specific talent, it can lose general population and still be prosperous.

As a result, prosperous shrinking cities are also more unequal. More prosperous cities, even when they are losing people, have both greater levels of education and greater levels of inequality.

Of course, population loss and economic decline do inherently affect each other. Population loss can result in decreased tax revenues from income tax or real estate. This reduced fiscal capacity may result in fewer or poorer social services, resulting in even more population loss, dubbed the “feedback cycle of shrinkage.” Cities can break the shrinkage cycle by “planning for less”—diminishing the supply of housing or municipal expenditures in order to match city infrastructure with its population without excess.

The fact of shrinking, or losing population, does not condemn cities to economic decline in and of itself. More than a third of America’s shrinking cities are still economically successful by acting as talent magnets. And like other winner cities, they too suffer from the same new urban crisis brought on by their success.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries that are relevant to Memphis.