It was not just that President Donald Trump did not defend this country’s most cherish values and the diversity that lies as a central strength. It was that when he did speak, he said that we should “cherish our history,” and there’s no way to interpret this except as a an intentional message aimed at white supremacists and neo-Confederates.

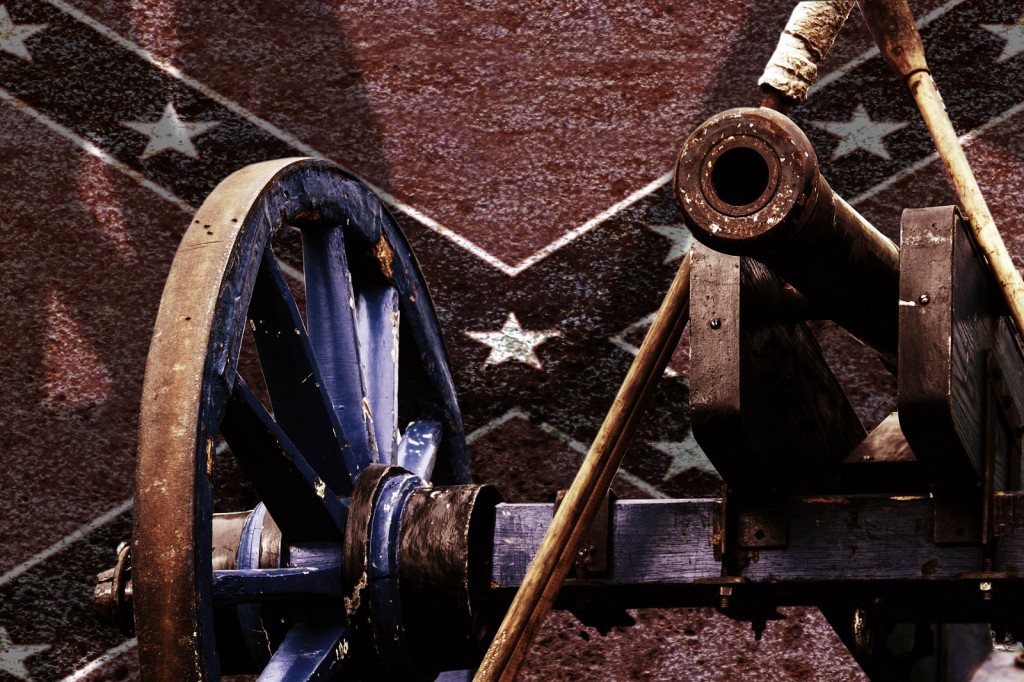

Let’s put this simply: there is no history to cherish when it comes to Confederate statues. They were placed in prominent civic sites across the South as a means of intimidating African Americans and sending the message that the Confederacy may not have won the war but its beliefs were living on.

This is the real history. It is ugly and it is obvious. Because of it, we have no patience with apologists or for those who peddle revisionist history about white supremacy.

In an article for MLK50, Confederates’ Lost Cause still cripples the South’s economy, I chronicled the history of the Lost Cause mythology in Memphis. There is no argument about the racist underpinnings for the statues of Nathan Bedford Forrest and Jefferson Davis in prominent Memphis parks. The article provides the context for the Forrest statue and its connections to national Confederate Veterans conventions in Memphis in the first couple of decades in the 20th century and the 1964 erection of the Davis statue just days before Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. received the Nobel Prize for Peace.

Here’s the article:

A direct line runs from the myth of the Lost Cause to the reality of lost opportunity in much of the Deep South.

To understand this, you only need to compare a map of the slave states of the Old South at the time of the Civil War to present-day maps that show America’s most entrenched poverty, low educational attainment, poorest health outcomes and sputtering economies. The maps are almost identical, illustrating how clinging to romanticized notions of Confederate heritage in the Deep South Confederate states of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, South Carolina and Texas — later joined by Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia — led to an economy dependent on worker exploitation, low wages and low government investment in human capital.

The 2014 U.S. Census shows the South has the highest percent of population living in poverty of all regions — 17 percent; the highest percent of adults reporting fair or poor health — 20 percent; highest rate of infant mortality — 6.7 deaths per 1,000 live births; and lowest educational attainment, with 10 states of the Confederacy finishing among the bottom 18 states in high school graduation. In rankings of the 50 largest metro areas, the Memphis Metropolitan Statistical Area persistently ranks in the bottom in these same indicators.

The maps make a persuasive case that the Lost Cause has been a drag on the former Confederate states: The willful twisting of historical fact shaped economic decisions that still cost the South opportunity and prosperity today, when success is defined by high-skilled, highly educated workers in an infrastructure that connects cities to a global marketplace.

And yet, the revisionists persist, like the Sons of Confederate Veterans, which held its “reunion gathering” in Memphis July 18–23 aimed at “insuring (sic) that a true history of the 1861–1865 period is preserved for future generations.” It’s a place where the false history about the antebellum South features stories about state’s rights, chivalry and heroism, happy and faithful slaves treated as members of the family, and stoic Southern women who sacrificed their loved ones to the cause of liberty and freedom, all while explaining away the racism memorialized in statues like those of Nathan Bedford Forrest and Jefferson Davis.

If the Lost Causers were merely confederates in rewriting American history, it would be easy to dismiss them as sound and fury signifying nothing; however, their attitudes and beliefs for 150 years have perpetuated discrimination, marginalized African Americans, deprived equal rights and built an economy predicated on low-skill workers.

This distortion of history was embraced and propelled by Hollywood, beginning with the heroic portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan in 1915’s Birth of a Nation and continuing with dozens of films into the 1970s built around sympathetic portrayals of noble former Confederate soldiers. It was a theme powered by 1936 best seller, Gone With the Wind, which won a Pulitzer Prize and became an influential movie in 1939 that won eight Academy Awards, including best picture. As popular culture advanced the Lost Cause narrative, Hollywood consistently ignored the horrors of slavery and pretended that the forced labor of millions of men and women was just a footnote, instead of the primary cause, that led to the South’s secession from the Union.

Neo-Confederates sentimentalize the stories and assert that it was economic and cultural issues that drove the Confederate states out of the Union, but all of the arguments lead to the same place: Preserving slavery was the motivating issue for secession and war. Any other reading of history is disingenuous, deceitful and odious.

In time, it was not considered genteel in the South to defend slavery, so it had to be explained in other ways — ways like heroism. The Lost Cause became the force behind the instruments of white supremacy, expressed by the naming of parks and streets and the erection of statues and monuments honoring heroes of the Confederacy.

The message to African Americans was unequivocal: We may not have won the war, but we will not abandon the core beliefs that sent us to battle.

To read more, click here.

**

Join us at the Smart City Memphis Facebook page for daily articles, reports, and commentaries relevant to Memphis.

yep. just checking. still stuck in 1968.

So when will black voters completely divest themselves from the Democratic Party, and oppose it on all levels, which was the backbone of the Confederacy?

Anonymous 9:00: Absurd comment.

Anonymous 9:30: African Americans, following the Civil War, were largely Republican. In fact, the legendary Robert Church was a powerful leader of the Republican Party at a national level. Sadly, over time, especially during Jim Crow days, African Americans had no political sanctuary but eventually, with the Democratic Party eventually taking action to seat racially diverse state delegations, it was seen as the party responding to concerns of African Americans. This was particularly stark with the dichotomy between presidential candidates. African Americans have been abandoned and marginalized by both political parties over the past 150 years but it seems pretty clear that for today, they are making the right decision.

What Anonymous 2 refuses to accept is that the party of Lincoln has, for the last 40 years, become the party of Jefferson Davis and Alexander Stephens.

Thanks, Steve.

9:30: “Let’s just use the benefits of the plantation party, aka, the Democratic Party. It’s not perfect, but its the best our people have.”

See LBJ’s comments on the 1964 Civil Rights bill. Racism and prejudice personified.

The question remains: when will blacks completely divest themselves from the party of the Old Confederacy? Segregation and Jim Crow were promulgated by the Democrats. The Klan emanated from the Democratic Party. George Wallace was not a member of the GOP. Remember, Lee and Forrest were not Republicans.

Those confederate statues in Memphis and other cities represent an important part of our national history that can never be erased by simply removing them or renaming parks. As a black citizen i totally reject the values they represent but don’t think we should try and revise history by removal. We should remember the wrongs of the past and work to never go that way again, but I don’t think we should try and gloss it over by removing them. We can learn lots of good lessons from their continued presence in our city.

42: The erection of the statues themselves revised history and as a result, they don’t represent history at all. They mock it. They are history as the Lost Cause wanted to revise it.

Also, statues reflect the values of a city and for that reason too, we think they should go. We don’t think you teach the cruelty of racism by leaving up statues celebrating a racist past.

This author knows no Republican who has written a book defending slavery. Alexander Stephens did.

And who was Stephens? A Democrat. This author’s argument has now been strengthened.

For the reasons that the monuments must be removed, the same reasons demand that black people remove themselves from the Democratic Party. It is the party of white supremacy and segregation.

The monuments are clearly associated with slavery and racism.

The Democratic Party is clearly associated with slavery and racism.

Sorry but I just don’t think putting up those statues “revised” history or “mock” it. Instead they are a stark reminder of a terrible and dark period in our history. That’s not revision, it’s fact. It happened. As an African American, I’m not offended by their presence and don’t think the statues reflect our Memphis values and they don’t “celebrate” the past one bit. They are reminders of the past that we should never forget.

We hope you’ll read the MLK50 article. It’s clear that the statues were erected in a very deliberate attempt to rewrite history. If this is about portraying the history of this dark period of our history, where are the statues of the people who resisted the racism at risks to their lives. One sided history is no history at all.

Smart City – great article. Sorry that the very mention of these embarrassing statues invites the confederate-loving nuts into your world…agree with your point of view, as usual, as you are seeing the big picture and how these ridiculous monuments prevent us from putting our best face to the world.

Right on, as always, SCM. Let’s get those embarrassing symbols moved (and fast)!

Our “best face” to the world should show our full and total complexion, including potmarks, blemishes, scars and colors of all types I know many African Americans in Memphis who are not one bit “offended” by the confederate statues. Instead they view the as reminders of a dark period in our history that can never be “erased” All of our children will learn from them.

I’d rather more embarrassing President Trump be removed than any of these statues. I’m a life long Memphian who is proud of my family’s slave roots. These confederate monuments just don’t bother me any at all.

I’d likke to see the statues removed but fear there would be bigger riots in Memphis than there were in Charlottesville Virginia. Lots of racists in this city and suburbs

Anonymous 12:44: We all should be offended by Confederate statues.

When will black people remove themselves from the ugliness and offense of the Democratic Party?

I believe that the state has laws on the books that prevent removal of

the confederate statues.

If you would read the article, it mentions state law. And earlier anonymous, the Demo wuestipn has been answered.

Why has the push to remove confederate monuments only surfaced in recent years? These statues have been around for a very long time.

Perry: We can remember people calling for the statues removal many years ago, but it’s picked up momentum lately with the broad-based push to fight racism and for monuments to real American heroes.

I’ve actually changed positions about this. I think our two Confederate monuments should be moved. I’m weary of hearing about it. Hopefully by picking this easy, low hanging fruit, it will inspire the ‘masses’ to look in the mirror and address the real issues holding back our society, the one’s only they have the power to address. Lot’s of people ARE trying. Maybe we’re finally turning the ship a little. I like and have confidence in the leadership of our city. However the days of ‘I’ve got a problem, what are you going to do about it?’ are slipping away.

Time to address real issues and stop wasting time on things such as ‘why The Orpheum shows Gone With the Wind’ every Summer. These are interesting days for sure. And for the thought police, keep your hands off my Lynyrd Skynyrd records.

Forrest and his wife were dug up from their proper grave and dragged to Health Science Park in 1904 for several reasons; One, to venerate and glorify the traitorous act of attempting to destroy this United States and second, to insure that black people knew who was in charge. If this was just about history being told in Health Science Park, then a plaque might mention Forrest’s many famous slave yards in Memphis, his notorious massacre of Black Union soldiers at Fort Pillow and last but not least, his famous quote found in the book, That Devil Forrest,, ” If we ain’t fighten for slavery, what the hell are we fighting for?” If it was just about history, the ones who won the war would be celebrated. U. S. Grant should have his own statue right next to Forrest facing North while riding his horse, ole Jeff Davis. Faulkner summed up, ” In the south history is not dead. It’s not even past.” That GD Forrest statue proves that.

I think its obvious that Jeff Davis and NB Forrest statues are going to be moved. My question is where and who is going to pay for it. The Pink Palace is a museum that has a civil war section with some Forrest artifacts, would it be out of line to suggest the statues be moved to its grounds somewhere? maybe even inside the mansion? A fund raiser would probably easily pay for the moves. The graves are another matter, maybe just leave them be unless the family wants them moved back to Elmwood.